BERLIN : Scientists have found an inexpensive and environment-friendly way of producing electricity from heat using simple tools such as pencil, paper and conductive paint.

The materials are sufficient to convert a temperature difference into electricity via the thermoelectric effect, according to researchers at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB) in Germany.

In thermoelectric effect, if two metals of different temperatures are brought together, they can develop an electrical voltage.

This effect allows residual heat to be converted partially into electrical energy.

Residual heat is a by-product of almost all technological and natural processes, such as in power plants and household appliances, not to mention the human body.

It is also one of the most under-utilised energy sources in the world, researchers said.

Now, a team led by Professor Norbert Nickel at HZB has shown that the effect can be obtained much more simply.

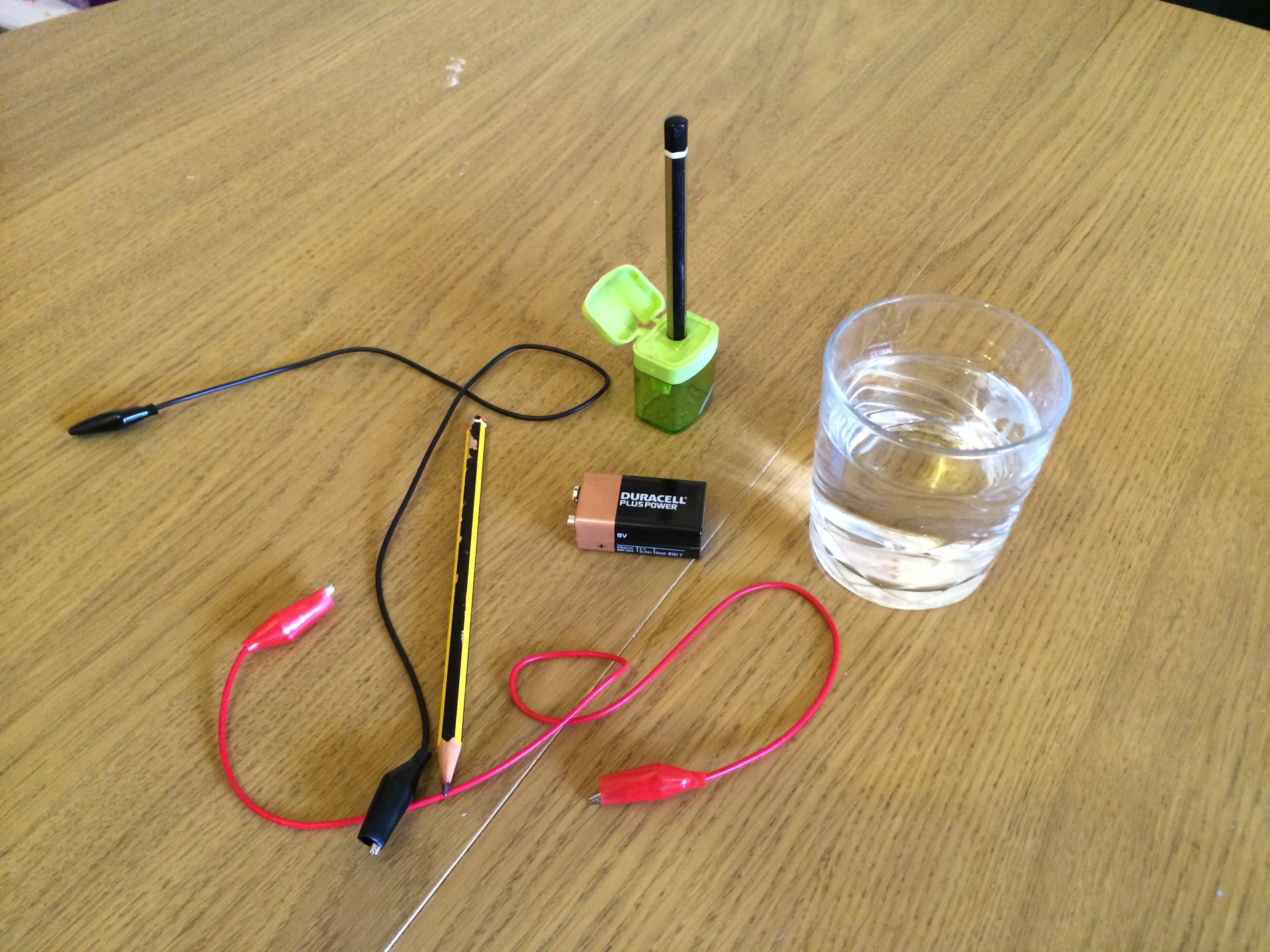

Using a normal HB-grade pencil, they covered a small area with pencil on ordinary photocopy paper. As a second material, they applied a transparent, conductive co-polymer paint (PEDOT: PSS) to the surface.

The pencil traces on the paper delivered a voltage comparable to other far more expensive nanocomposites that are currently used for flexible thermoelectric elements.

This voltage could be increased tenfold by adding indium selenide to the graphite from the pencil.

The researchers investigated graphite and co-polymer coating films using a scanning electron microscope and Raman scattering at HZB.

“The results were very surprising for us as well,” said Nickel.

“But we have now found an explanation of why this works so well – the pencil deposit left on the paper forms a surface characterised by unordered graphite flakes, some graphene, and clay.

“While this only slightly reduces the electrical conductivity, heat is transported much less effectively,” said Nickel.

These simple constituents might be usable in the future to print extremely inexpensive, environmentally friendly, and non-toxic thermoelectric components onto paper, researchers said.

Such tiny and flexible components could also be used directly on the body and could use body heat to operate small devices or sensors, they said. (AGENCIES)

Trending Now

E-Paper