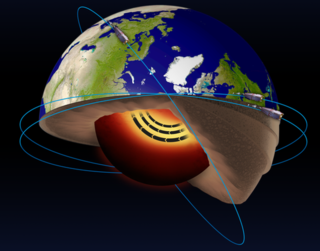

LONDON: Scientists have discovered a jet stream within the Earth’s molten iron core using the latest satellite data that helps create an ‘X-ray’ view of the planet.

Researchers from the University of Leeds in the UK found the position of the jet stream aligns with a boundary between two different regions in the core.

The jet is likely to be caused by liquid in the core moving towards this boundary from both sides, which is squeezed out sideways.

“The European Space Agency’s Swarm satellites are providing our sharpest X-ray image yet of the core. We have not only seen this jet stream clearly for the first time, but we understand why it is there,” said lead researcher Phil Livermore from the University of Leeds.

“We can explain it as an accelerating band of molten iron circling the North Pole, like the jet stream in the atmosphere,” said Livermore.

Because of the core’s remote location under 3,000 kilometres of rock, for many years scientists have studied the Earth’s core by measuring the planet’s magnetic field – one of the few options available.

Previous research had found that changes in the magnetic field indicated that iron in the outer core was moving faster in the northern hemisphere, mostly under Alaska and Siberia.

However, new data from the Swarm satellites has shown that these changes are actually caused by a jet stream moving at more than 40 kilometres per year.

This is three times faster than typical outer core speeds and hundreds of thousands of times faster than the speed at which the Earth’s tectonic plates move.

The European Space Agency’s Swarm mission features a trio of satellites which simultaneously measure and untangle the different magnetic signals which stem from Earth’s core, mantle, crust, oceans, ionosphere and magnetosphere.

They have provided the clearest information yet about the magnetic field created in the core.

The study found the position of the jet stream aligns with a boundary between two different regions in the core.

The jet is likely to be caused by liquid in the core moving towards this boundary from both sides, which is squeezed out sideways.

“Of course, you need a force to move the liquid towards the boundary. This could be provided by buoyancy, or perhaps more likely from changes in the magnetic field within the core,” said Rainer Hollerbach from Leeds.

“We know more about the Sun than the Earth’s core. The discovery of this jet is an exciting step in learning more about our planet’s inner workings,” said Chris Finlay from the Technical University of Denmark.

The study was published in Nature Geoscience. (AGENCIES)