Ashok Ogra

It’s difficult to find a garment as widely embraced, worn and loved the world over as jeans. Not only do youngsters wear them, but so do presidents, doctors, academicians, supermodels, farmers, workers, housewives and even unemployed people.

And ask any one of them why they wear jeans, you are likely to get a range of answers. For some, they are comfortable, durable and easy – for others they are sexy and cool. Jeans mean different things to different people. This explains their broad appeal.

Noted anthropologist Danny Miller, who has studied the phenomenon of wearing jeans writes that out of every 100 people who walk by, he counted that “almost half the population wore jeans on a given day. Jeans are everywhere, he says. ”The reason for their success has as much to do with their cultural meaning as their physical construction.”

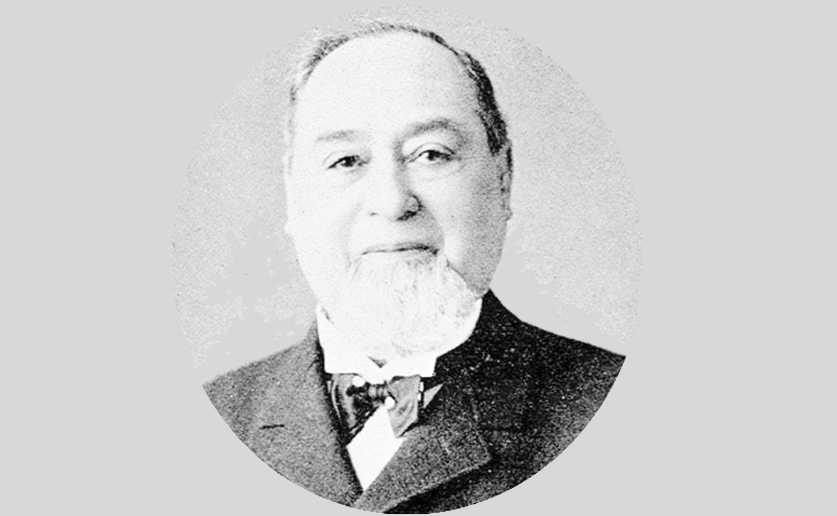

When a Nevada tailor called Jacob Davis was asked to make a pair of sturdy trousers for a  local woodcutter, he struck upon the idea of reinforcing them with rivets. They proved extremely durable and were soon in high demand. Davis realised the potential of his product but couldn’t afford to patent it. He wrote to his fabric supplier, the San Francisco merchant, Levi Strauss, for help. The rest, as they say, is history. The patent was granted to Levi Strauss on 20 May 1873 – exactly 150 years ago. That marked the birth of mass- produced denim.

local woodcutter, he struck upon the idea of reinforcing them with rivets. They proved extremely durable and were soon in high demand. Davis realised the potential of his product but couldn’t afford to patent it. He wrote to his fabric supplier, the San Francisco merchant, Levi Strauss, for help. The rest, as they say, is history. The patent was granted to Levi Strauss on 20 May 1873 – exactly 150 years ago. That marked the birth of mass- produced denim.

Soon, denim became a ubiquitous fashion fix all over America and Europe.

Today, it might seem odd to outlaw a pigment, but that’s what European monarchs did in a strangely zealous campaign against indigo.

To many Europeans, using the dye seemed unpleasant. The fermenting process yielded a putrid stench not unlike that of a decaying body.

Plus, indigo represented a threat to European textile merchants who had heavily invested in woad, a homegrown source of blue dye. Weavers were told it would damage their cloth.

Governments got the message. Germany banned “the devil’s dye” for more than 100 years, beginning in 1577, while England banned it from 1581 to 1660. In France in 1598, King Henry IV favored woad producers by banning the import of indigo, and in 1609 decreed that anyone using the dye would be executed.

Still, the dye’s resistance to running and fading couldn’t be denied, and by the 18th century it was all the rage in Europe.

Prior to the 1930s, denim jeans were almost exclusively limited to people who needed hardy pants to do their jobs (miners, farmers, ranchers, etc.) Not only were they more durable, but each pair of jeans began to tell the story of the worker and his work. In 1939 however, visionary John Ford directed a critically acclaimed

STAGE COACH. The film was a smashing success and made the relatively unknown John Wayne a star. Wayne wore Levi’s jeans and his outfit would typify a generation’s image of the cowboy.

Elvis Presley’s musical film JAILHOUSE ROCK (1957) saw the King in all denim as a prison inmate with a golden voice. His hip-gyrating antics were a national sensation, and every teen in the country wanted the same jeans. When they did start to be worn as casual wear, it was a startling symbol of rebellion – the spirit captured by Marlon Brando in his 1953 film THE WILD ONE. As one film critic wrote: “Hollywood costume designers put all the bad boys in denim.”

The initial explosion of denim into the world of casual wear had more to do with what jeans had come to symbolize. s of their legs and hips.

During the 1960s jeans had also spread to the American middle class. Protesting college students began wearing them as a token of solidarity with the working class – those most affected by racial discrimination and the war draft.

In the spring of 1965, demonstrators in Alabama, took to the streets in a series of marches to demand voting rights. It took Martin Luther King’s march on Washington to make jeans popular. It was here that civil rights activists were photographed with denim to dramatize how little had been accomplished since Reconstruction. The blue jeans fabric conquered both pop culture and fortified the civil rights movement. For much of the black community, the activists’ symbolism was obvious. Separate then; separate now.

It was soon co-opted by the mainstream. Hippies too took to denim to reflect their dissatisfaction with the materialistic world that is devoid of spirituality.

But jeans weren’t only a symbol of democratisation, they put different classes on a level playing field. They were affordable and hard-wearing, looked well worn as well as new, and didn’t have to be washed often or ironed at all. Today, jeans have become this neutral foundational garment. If you want to show you are relaxed, if you want to be relaxed, you wear jeans.

India too has a history of using clothing to convey political meaning and even as a strategy to incite change.

For example, in 1903, the wealthiest man in India at the time, the Nizam of Hyderabad, chose to wear a simple western suit to the 1903 Delhi Durbar, a ceremony marking the coronation of the British monarch. In so doing, he instigated the displeasure of a British colonial administration who liked to see their native rulers dressed as spectacles of South Asian finery.

Later, Gandhi Ji wore a dhoti to have tea at Buckingham Palace in 1931. The dhoti, made out of hand-spun cotton, was part of the larger Khadi movement to protest the import of cheaper-than-local machine-made British products that led to the decline of the Indian textile industry.

In India, the clamour for jeans received a huge boost when irresistible bad boy film star Amitabh Bachchan (Jai) and Dhamendra (Veeru) sported jeans in the 1975 mega-blockbuster, SHOLAY. The Sippys didn’t want their cast to be cliches, writes Anupama Chopra in the book SHOLAY, REMAKING OF A CLASSIC. And so, atypical of its time, Ramesh Sippy dressed his heroes in denims, western cowboy style.

Around the same time, actresses Parveen Babi and Zeenat Aman flagged the fabric as fashionable for women. Thus, the popularity of Bollywood films thrust denim into the limelight.

Initially, Indians turned to tailors to stitch their jeans. However, India’s economic liberalization initiated in 1991 made foreign brands easy to buy. Ripped jeans came soon after with the increased exposure to international trends.

It is fair to say that initially jeans in India were associated with the West, modernity and youth culture. That is to an extent still true. But lately jeans have acquired the added association with protest and dissent.

Curiously, jeans have continued to make waves in the 21st century. In the run-up to the 2006 presidential elections in Belarus, activists marched to protest what they characterized as a sham vote in support of an autocratic government. After police seized the opposition’s flags at a pre-election rally, one protester tied a denim shirt to a stick, creating a makeshift flag and giving rise to the movement’s eventual name: the “Jeans Revolution.” Internationally known designer Giorgio Armani best describes the power of jeans: “Jeans represent democracy in fashion.”

Few weeks ago, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu unwittingly turned himself into an object of ridicule for claiming that among the various freedoms denied to Iranians was the right to wear jeans. In no time at all, social media immediately buzzed into life to prove Netanyahu wrong – at least with regard to jeans-wearing. Setting aside all the claims and counterclaims that might be made (and have been made) between Israel and Iran, what is striking about this example is that jeans-wearing should have been invoked as an indicator of a free citizenry in the first place.

It is this association that jeans have acquired over the last 150 years, that Catherine McKinley reflects in her book INDIGO: IN SEARCH OF COLOR THAT SEDUCED THE WORLD and beautifully sums up the power of denim, “No color has been prized so highly for so long.” Today, we can safely proclaim that fashion fades but denims are eternal. 966)

(The author works for reputed Apeejay Education, Delhi)

Trending Now

E-Paper