Saloni Poddar

“Migration is often accompanied by a feeling of unavoidable disorientation, and the circumstances of 1947 would have pronounced this feeling. In most cases it would have created an involuntary distance between where one was born before Partition and where he moved after it, stretching out their identity sparsely between the original city of their birth and the adopted city of residence, which would lay their essence – strangely malleable.”

– Anchal Malhotra, historian.

Partition of India was an invisible inheritance. What comes to mind when we talk about ‘inheritance’? Heirlooms; ornaments studded with rubies, lapis lazuli rings, collector’s antiques, Renaissance paintings, property deeds, or maybe even a cash or bond bequest?

However, when we talk about ‘Partition Heirlooms’ I mean a latent, painful, deep-rooted trauma. These are small words though, for the feelings cannot be described in words. Nor can those memories be reconciled with. They still remain. Always will. I call the people who ‘survived’ the ‘Partition inheritors’ because although we cannot see that bequest physically, it is deeply imprinted in the memories of those who braved it.

The memory of Partition is fundamentally a memory of displacement. Millions of people were uprooted overnight, evicted from their ancestral homes, not having time to plan their escape. They had no choice but to accept their bleak fate. As the boundary commission demarcated borders on August 17th, 1947, millions of Sikhs and Hindus left their homes and hearths behind, just tied up their few belongings in bundles, and set out. They traveled kilometers upon kilometers on foot. Always wary. Worried about their safety. Their honor. They walked on. Hungry. Diseased. Tired. Hopeless.

Once Pandit Nehru, accompanied by Liaqat Ali, passed a procession of Sikh refugees, almost three miles long. Battered and exploited Sikhnis; their clothes bloodied and torn, trying to upkeep the little semblance of dignity they were left with, the once-proud, straight-backed Sikhs; turbans askew, hair shorn off. It was a tragic sight.

These refugees were mostly from the Sheikhupura district. Nehru was stopped and asked by an old Sikh woman, “If you wanted to partition the country why did you not first arrange for the exchange of population? See what misery has come to us all.”

A man remarked, “Are there any arrangements for us en route? We hope we will safely reach our Azad Hindustan.” Nehru did not answer. His heart was too full of dismay.

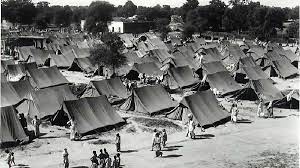

Those who survived the riots and violence managed to reach refugee camps, hoping their sufferings would shortly come to an end but the sights and conditions that awaited them were ghastly.

Most camps were makeshift, having little arrangements. People used whatever material they could find like fabric, sticks, and charpoys to create shelter for themselves. These fragile tents were where most Sikhs made homes from days to weeks and even months.

Some camps were, fortunately, set up amidst the rubble of recently vacated houses. These were thought of as ‘striking gold’ as people used bricks, wood, and broken furniture from these sites to create a semblance of civilization for themselves.

Walls of bricks, piled up loosely atop each other, used to demarcate personal spaces. Ironically, however, those unstable walls were symbolic of the lives of the people residing within them.

As thousands of displaced Sikhs and Hindus reached refugee camps across, in East Punjab, food became scarce and diseases rampant. Even chapatis had to be rationed. Each person was entitled to two ‘rotis’ a day! People who lost family members to diseases or natural death often did not declare their demise, fearing the loss of the two life-giving rotis!!

Imagine the plight of the hard-working, robust, Sikh farmer of Punjab, the one who feeds the whole nation… imagine him standing in a queue, flashing his ration card, helplessly collecting ‘two rotis’ each to feed his family for the entire day. Could he have been worse off?

The newly-formed government was doing what it could. There was help from other countries as well, but the severity and sheer numbers of displaced people had been seriously underestimated. Eventually, things became better. The memories blurred a fraction. The scars healed gradually. People settled in other parts of India. But Sikhs never really forgot.

Fissures remained even after the wounds healed. The pain of being uprooted. The suffering of losing their fields. Their lives. Their families. One can never get over the trauma of being uprooted or displaced. It takes years for the plant to get acclimatized to new surroundings. We are talking about people. A complete race.

Trending Now

E-Paper