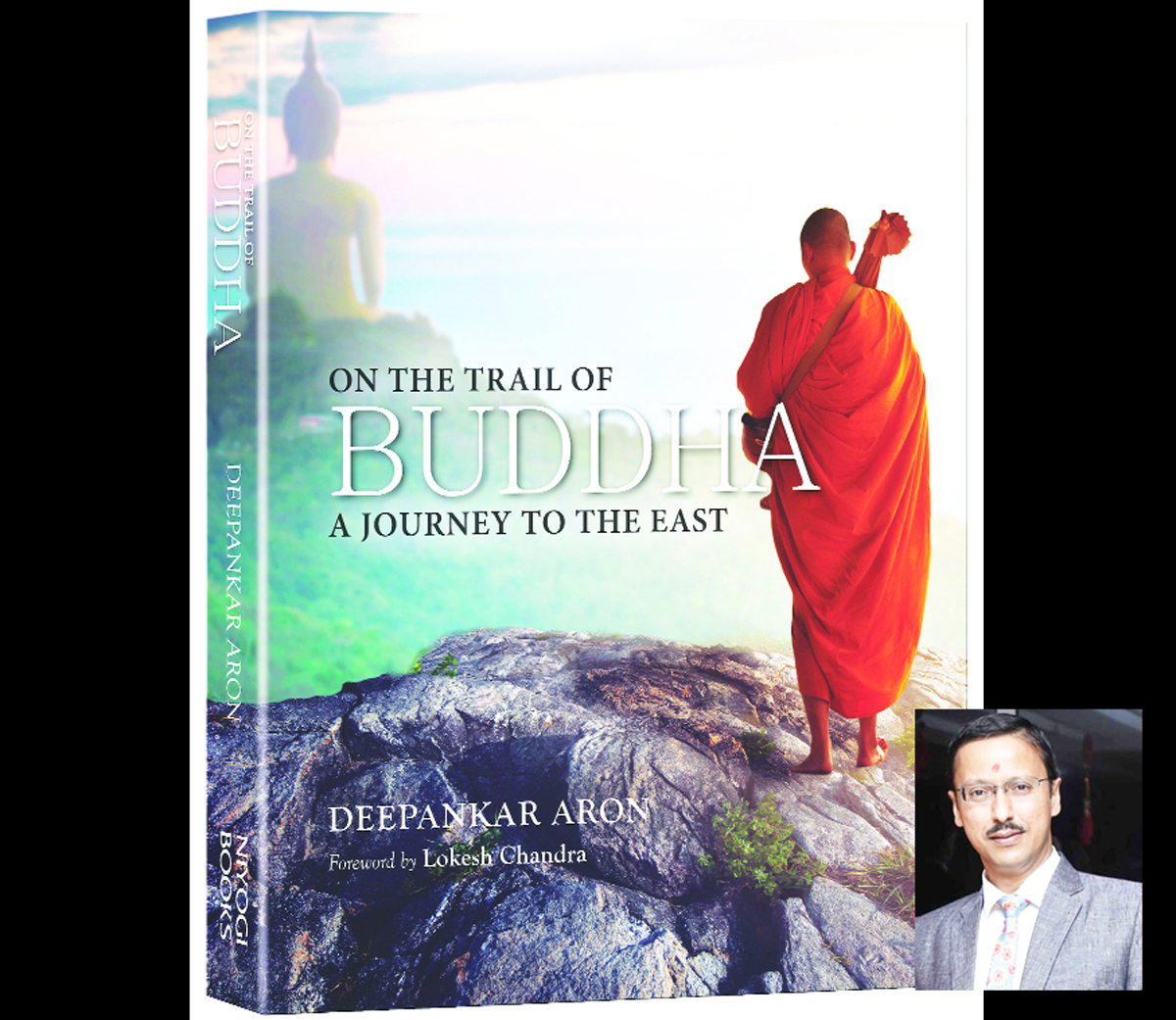

Deepankar Aron has been on a discovery route looking for the Buddhist connection binding India, China and the Far East. His new book On the Trail of Buddha is the culmination of those travels. The author speaks to Ranjita Biswas on his experiences

Deepankar Aron is a senior bureaucrat, not a travel-writer or photographer by profession, forever zooming off to a new destination. Yet, the way Buddhism connected many parts of Asia for centuries has fascinated him enough to travel widely in areas where once the message of Buddha from India was carried by travellers and monks.

Excerpts of an interview:

This book seems almost like a diary on a pilgrimage route – chasing the Buddhist trail, as it were, for you. How long did the book take to materialise?

The ‘book’ was never really written with a book in mind. The travels in East Asia were spread over a period of six years commencing with the Kailash Manasarovar Yatra in 2009 in which I had gone as a Liaison Officer appointed by the Ministry of External Affairs, and culminating in 2015 which also marked an end to my diplomatic assignment in Hong Kong.

The book is indeed a travelogue of close to 100 destinations scattered over the East Asia from China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, Hong Kong SAR and Taiwan, including Tibet. It took another five years be formed into a book, so you can say, it ‘took’ 11 years in all.

So the common theme is the message of Buddha that spread from India?

The Buddhist trail in the book is indeed the unifying thread that runs through from India to all over East Asia during the course of the last 2000 years. These travels unveiled for me the enormity of the exchanges and commonalities, especially in the first millennium when modern modes of communication and travel were absent.

However, for me this wasn’t something that so apparent at the beginning but in the course of these travels the strong linkages of culture, philosophy, art and architecture between India and East Asia centered around Buddhism started emerging.

What has been your inspiration behind the travels that culminated in the book?

Well, the inspiration has been the old Indian adage of Vasudhaiva Kutambakam’ –‘the whole world is one family’!

In essence, it is the spiritual message of ‘Oneness’ that emerges, something which both Vedanta and Buddhism talk about. The title of the book is inspired by the A Journey to the West written by Wu Cheng’en in 16th century China, based on the travels of Xuan Zang or Huein Tsang (in India), undertaken between AD 628 and 645 to India in search of the sutras.

Another reason for writing the book is that very little of the vastness and depth of this exchange is known, even to us educated Indians. A lot more transpired than what is recorded in our school history books; it was an eye opener for me.

You talk a lot about the remarkable cave temples in China s. What do you think is behind Buddhist monks’ desire to carve inside caves? In India too we have examples like Ajanta, , Nilgiri- Udaigiri caves in Odisha, etc.

Since Buddhism spread along with trade through the Silk Road and various other mountain paths cutting across difficult terrains, it was a necessity to have shelters on the way which could not just provide food and security, but also provide a place of quietude for worshipping and meditating to recoup the spiritual energy needed to undertake these arduous journeys. Thus, the best place to have a ‘safe home’ automatically became a cave, a natural shelter.

Obviously, art in the form of frescoes and grottoes could best be preserved for posterity, if made inside these caves and thank God, they did that, for otherwise we won’t be seeing them today as they could have been lost to vagaries of time and destruction. It is well known that sunlight damages the colors of paintings. Thus, the frescoes of Ajanta-Ellora or of Dunhuang caves or those of Alchi caves temples in Ladakh have been well preserved thousands of years afterwards.

You travelled to South Korea and Japan as well, chasing the Buddha. Increasingly, it seems how invaluable was India’s contribution to the religious-cultural maps of these countries but it’s less written about.

Absolutely, there was a tremendous amount of exchange between India and Korea on one hand and India and Japan on the other. Buddha’s relics called ‘Sari or Sarira’ came right upto Korea; there are mountains in Korea (Gaya-san) named after Gaya; one of the most popular sects of Buddhism in Korea is called the Jogye order which is same as Dhyan (India) or Chan (China) or Zen in Japan. There was even a princess from Ayodhya who married a Korean king some 2000 years ago as per legend. In fact, 10 per cent of all Koreans (particularly from the Kim clan) say they can trace their ancestry to this princess from Ayodhya!

Likewise, Saraswati is popular in Japan as Benzaiten. Many of the World Heritage Sites of Kyoto are Buddhist monasteries. In quite a few temples such as Sanjusangen-do in Japan you will find Sanskrit names of the gods and goddesses coexisting with the Japanese names.

We seem to have lost the free flowing exchange of ideas on cultural affinities between India and China down the ages due to various reasons, including political ones. How important is it to relook at them today under rising tensions between the two countries?

I think it’s extremely important to understand the enormity of the very close civilizational linkages between India and China for more than 2000 years, particularly in the first millennium. More so, in the context of the current situation.

Today, this rich legacy of a common cultural and spiritual heritage that can still be witnessed from Kashgar in the western- most regions of China to Shanghai in the east, from upper reaches of China bordering Mongolia down south upto Taiwan is a fitting testimony to a harmonious and peaceful exchange between the two ancient civilizations. (TWF)