Nitya Chakraborty

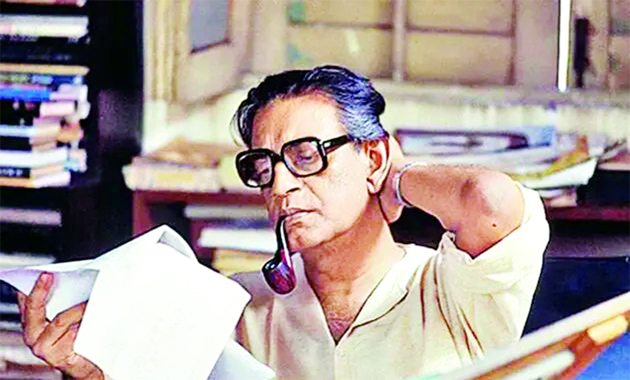

The legend of the Indian cinema, Satyajit Ray, has crossed one more year after his centenary celebrations began on May 2 of last year. The last icon of what is termed as Bengal Renaissance, died at the age of only 71 on April 23, 1992. Though his last film ‘Agantuk’ was released in 1991, just a year before his death, the last eight years of his life since 1984 were controlled with strict medical supervision in view of his heart disease.

In fact, ‘Ghare Baire’ released in 1984 was the last film in which Ray functioned normally bearing all the hassles of outdoor shooting. He was a perfectionist to the core and he sought complete control on every area of film-making, including camera, editing, script, dialogue, costume design, where his wife Bejoya was a big help, and finally, music. But this sort of total supervision was not possible after his heart condition worsened. Doctors advised him rest but he was restless to make more films.

So many ideas were haunting him. The doctors finally advised him that he could do films if they involved mostly indoor shooting for limited hours. On that basis, Ray conceived the stories and three feature films: ‘Ganashatru’, ‘Sakha Prasakha’ and ‘ Agantuk’ were made in 1989, 1990 and 1991 respectively. Before that, in 1987, Satyajit did a 30-minute documentary on his father Sukumar Ray produced by the West Bengal Government.

Each film by Ray had different backgrounds and focus areas, but the passion with which he made his debut film ‘Pather Panchali’ and the consequent trials and tribulations he faced in the course of its making, have all the hallmarks of a major film biopic. This great journey in late 1940s and early 1950s by Ray and his friends to make a neo-realist film in India on the pattern of Vittirio De Sica’s ‘Bicycle Thieves’ also signalled how Ray, who was a great lover of Hollywood films including the blockbusters, changed his view and co-opted neo-realism for Indian cinema.

His stay in London for six months in 1950 gave him a fresh perspective on the trends in world cinema. He saw 99 films in London and a few more in Paris. Both Ray and his new wife, Bejoya – who had been his girlfriend for more than a decade then, and was an equal partner in all of his cerebral activities – had a gala time during this visit abroad. Ray and Bejoya became members of the London Film Club and had frequent sessions with the British film leaders like Lindsay Anderson and Gavin Lambert. Both discussed intensely on the timbre and type of film they should do after returning to Calcutta.

Ray saw some of the so-called ‘New Wave’ films of France and other European countries. The films did not excite him enough, though he appreciated some of the new arenas which these filmmakers, especially of France, tried to explore. But, by then at the age of 29 in 1950, he had enough maturity to take a decision. He was fully aware of the state of the Indian nation after barely three years of independence and how Indian film industry needed a new turn based on the neo-realism of the Italian variety and not French new wave or even the Hollywood blockbuster. Satyajit Ray was overwhelmed after seeing ‘Rashomon’ by Akira Kurosawa of Japan. If Japan, an Asian country, could make such an outstanding film, why not he in India?

So, on the couple’s way back to India on ship, Ray decided that he would make ‘Pather Panchali’ at all costs. This was very much in his mind earlier also, but during their London visit, they both found that the ‘Pather Panchali’ story fitted in with their neo-realistic view. The young couple knew that the challenge of getting financial backing for this film, by a newcomer with no experience in filmmaking, would be a Herculean one, but the passion was so high that Ray began all his preparations in full steam, including illustrations (now called ‘storyboard’) and draft of the script. Ray was a great fan of the writer Bhibhuti Bhusan Bandyopadhyay. But he was at the same time sure that he was making a film out of the great novel and filmmaking was a different art form. The book needed lot of pruning and shaping for the cinematic adaptation.

Ray was fascinated by the humanism of the novel and its ring of truth. He wrote in an article later: “I knew I could not go in this film beyond the first half of the book which ended with the family’s departure for Benares – but at the same time, I felt that to cast the thing into a mould of cut and drive narrative would be wrong. The script had to retain some rambling quality of the novel because that in itself contained a clue to the feel of authenticity, life in a poor Bengali village does ramble.”

Ray had definite views about how a good film may be made from a great book. As Ray explained in his article ‘Should a Film Maker be Original?’ that all great filmmakers have fashioned classics out of other people’s stories. He may borrow his material, but he may colour it with his own experience of medium. Then and only then, the completed film will be his own, as unmistakably as Kalidas’s Sakuntala is Kalidas’s and not Vyas’s. Ray then says:”Compare a good film of a book with the book itself and you will find that the original has undergone a process of thorough reshaping. The reason is simple, but needs to be stressed repeatedly — books are not primarily meant to be filmed.”

According to Ray, if books are written to be filmed, they would read like scenarios and if they were good scenarios, they would probably read badly as literature, for scenarios are no more than indications in words of what is really meant to be conveyed in images. Then he elaborates: “I have made a trilogy of films based on the two well-known Bengali novels of Bibhuti Bhusan. Pather Panchali is a great book, a classic of Bengali literature with many qualities, visual as well as emotional which are transcribable on film. I tried to retain these qualities in the film.”

As Ray gathered his team of maverick people around him who were equally hungry for doing something new for Bengali cinema, work followed. However, when Ray presented his concept, script and the drawings of the shots to the leading producers of West Bengal, the common reaction was:”The idea is wonderful, but you have no experience, how will you do it?” From then on, the search for financiers for Pather Panchali continued and in the process, Ray was cheated three times by the small-time brokers who promised to give the funds after getting some money as advance.

The twists and turns of Ray and his friends in their long search for mobilizing funds for making Pather Panchali over the next four years after his return from London in 1950, are well known, but the most gripping of the anecdotes was when in the course of shooting, in a remote village, the promised funds had not come through, but the crew had to be fed. Ray’s team member Anil Choudhury was rushed to Bejoya immediately. Anil took a pair of gold bangles from her and pawned them in a known shop in lieu of some money to feed the crew. However, Bejoya was pregnant at that time and one day she was supposed to wear those bangles given to her by Ray’s mother Suprabha on the auspicious occasion that the Bengalees call ‘Swad’, a special day for pregnant mothers.

Anil salvaged the situation by persuading another woman known to him to loan her ornaments for a few days and put those in the pawn shop and gave back Bejoya’s bangles on the scheduled day, so that she wore those in a normal manner and her mother-in-law had no doubts. After the function, Anil Choudhury took back those from Bejoya and gave them back to the pawnshop owner and took the other ornaments for giving back to the lady who helped.

There was another interesting story. Satyajit was too tall compared to common Bengalis. His height was six feet four and half inches. Those days in 1950s, they had very little money for spending on taxis. The team members had to travel by buses. Satyajit with his height was not comfortable standing as a passenger inside the buses; his head touched the ceiling of the buses in those days, and he had to stoop straining his neck. So, he always used to stand on the stairs of the bus. The conductors understood his problem, so they also did not mind.

The French director Jean Renoir told Ray in 1949 in the course of a meeting: ‘If you could only shake Hollywood out of your system and evolve your own style, you would be making great films’. Yes, Ray did precisely that and charted his own course based on his own understanding of his surroundings, the Indian ethos and how to use the film medium to convey to the viewers his perception about the issues he believed in. And that had been an incredible journey indeed. (IPA)