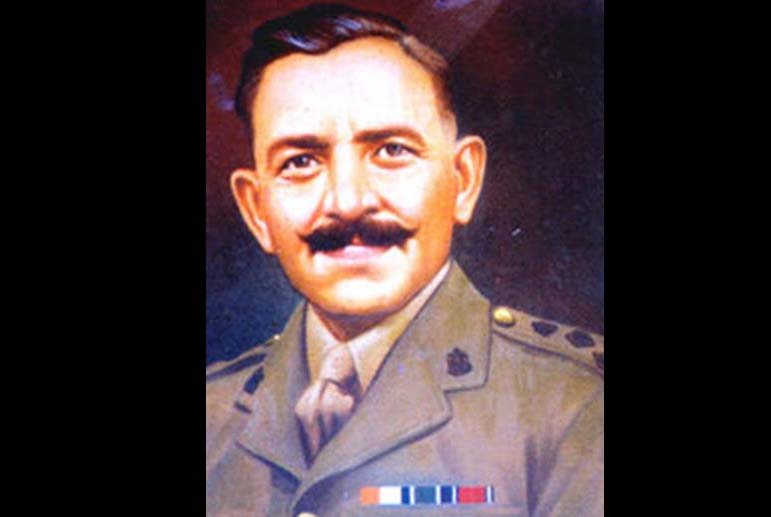

Col Ajay K Raina

Dogras are known for their soldierly qualities. The military history of our army is replete with numerous stories of their valour and sacrifices.Brig Rajinder Singh, Chief of Staff of J&K State forces during the 1947 invasion, was no different. Many readers know about his last action. This write-up attempts to highlight the circumstances and influences that shaped his personality and made him a military leader of such a stature.

He was born on 14 June 1899 in the small village of Bagoona (now renamed Rajinder Singh Pura, after him), some 35 km East of Jammu city. His family belonged to the Dalpatian clan of Jamwal Rajputs. The tradition of bravery and sacrifice ran deep in his family, with his illustrious ancestor, GenBaj Singh, having sacrificed himself only four years earlier while fighting in Chitral. His grandfather was a war veteran with seven battle scars on his body. His father, Subedar Lakha Singh, was a JCO in the State Forces. However, within six months of his birth, Rajinder Singh lost his father.

LtCol Govind Singh, one of his uncles, took it upon himself to bring up Rajinder, who had no one else to support him. Family loyalty came to his rescue. He was forgotten in the group of his contemporaries as he grew into a quiet, unassuming, obedient and studious young man. While his kind uncle supported him, he did miss parental guidance and plunged headlong into his studies to overcome the emptiness in his life. Educated in Jammu, he graduated from Prince of Wales College (now Gandhi Memorial Science College) Jammu in 1921. He did very well in his studies. In line with his family tradition, he was expected to seek a career in the army, and that was what he did.

In June 1921, soon after his graduation, he joined the State Forces as a Commissioned Officer. Once in the forces, the young Rajinder Singh devoted all his energies to mastering the art of soldiering and gave full play to the military genius that had so far laid hidden. His innate qualities saw him rising rapidly through the ranks. He was promoted to be a Capt in 1925, a Maj in 1927 and a Col in 1935. In May 1942, he became a Brig and was in line for his next rank.

After ex-British officer, MajGen HL Scott, was relieved of his duties by the Maharaja, Brig Rajinder Singh was appointed as the Chief of Staff of J&K State Forces on 24 September 1947.His appointment came at a time when the State was inexorably moving towards a deep military and political crisis.The Punjab and NWFP were on fire. The refugees were streaming into the State, seeking shelter and safety. The question of accession to either of the dominions was hanging fire. It was a tough time, indeed.

His first task during those turbulent times was reorganising the State’s defence. His predecessor had, intentionally or otherwise, deployed the State Army in a way that troops had been scattered in penny pockets, more as a police force rather than a cohesive fighting military. After a quick round of the forward areas and in view of the developing situation along the border in the Jammu region, he issued instructions to redeploy subunits so that each base could fight and hold on its own. The notion planted by the British that Pakistan would never attackthe State was something he refused to believe, and despite a glaring shortage of troops and resources, he set out to set things right. Poonch Brigade was raised during his initial days, and such a reorganisation actually saw Poonch through difficult days before the arrival of the Indian Army during the months to follow.

With Pakistan cutting all supplies to J&K State despite having signed the Standstill Agreement, the forces started feeling the heat. Because of the border skirmishes and the enemy action in the Jammu region, ammunition began to run short. Brig Rajinder Singh, using the links of LtCol KS Katoch, impressed upon Delhi to send in the war essentials, and the request was approved more than once both by Sardar Patel and Sardar Baldev Singh. Another issue is that the British officers, who were manning the subordinate appointments, never executed such approvals and the State had to pay a heavy price in the coming days.

His daughter, Usha Parmar, remembers that he was an ardent worshipper of Ma Bhagwati. He would support the education of many needy children either by paying their fees or getting the fees waived. He would also donate to help people marry off their daughters. He was not a rich man, though and all his philanthropic work meant strain on the family’s finances. He was a teetotaller but a chain smoker. However, once all his daughters decided to stage a small protest by picking up stubs and using those to copy his smoking style, he gave up smoking too!

He was a keen sportsman and would play tennis and squash with passion. Riding horses and hunting were his beloved hobbies, and he would indulge in those activities only when he could manage to find time from his busy schedule.

As can be seen, a combination of a tough childhood, some fine qualities (both innate and acquired) andthe Dogra ethos was instrumental in shaping his persona. And he would not think even once before taking a stand on the issues that he felt were worth the effort. Because of such a trait, he, on two occasions, had resigned from service but was talked into rejoining the force. The Maharaja regarded him well, and when he was elevated to the Chief of Staff position, he was not the seniormost in the military hierarchy.

And when it mattered the most, he took the concept of obedience to a different level when he executed the order given by his Commander-in-Chief to fight to the last man and last round. It happened on 22 October 1947 when the Pak army-led invaders drove into Muzaffarabad unopposed courtesy of own troops switching sides. That treachery meant the road to Srinagar lay open and unguarded after a handful of soldiers under their CO, Lt Col Narayan Singh Samyal, OBE, trying to fight traitors and invaders, were killed in action. Finally, it fell upon Brig Rajinder Singh, who, despite his senior-most position in the military hierarchy, led just about 100 Dogra soldiers to fight an unparalleled action along the Jhelum Valley Road between Garhi (ahead of Uri) and Baramulla.

As more than 6,000 frenzied men who had been promised women and wealth as war booty kept on assaulting the numerable Dogra braves, Brig Rajinder led his men in a series of well-planned tactical withdrawal manoeuvres over the next four days. His decision to blow up the Uri bridge proved to be a masterstroke, and the enemy’s plan to reach Srinagar on 23 October to capture the Maharaja alive and make him sign the Instrument of Accession, suddenly went haywire. His men were dying and getting wounded as a few more were rushed from the rear. However, at no point during that action did he have more than 100 able-bodied soldiers under him. Fighting without rest and proper food, the Dogras, under their Chief of Staff, kept the enemy away from Baramulla until 27 October. By that time, chips were down, and Brig Rajinder had been badly wounded. At that stage, he refused to be evacuated and ordered his men to leave him under a culvert. With a pistol in his hand, he stayed behind, thus becoming the last man to try and stop the enemy. He was never seen again after that early morning of 27 October.

It is unfortunate that history was twisted to declare other non-consequential entities as ‘saviours’ of Kashmir during the following years. Such a narrative is believed by many as gospel even though none of such personnel ever fired a bullet or fought the invaders. Such an attempt amounts to humiliation to those selfless soldiers who gave up their lives fighting so that the Indian Army could land and take on the duty of protecting the Valley. It goes to the credit of Brig Rajinder Singh and his men that within a few hours of his laying down his life, the first unit of the Indian Army landed at Srinagar. There has been no other instance anywhere in the world wherein a Chief of Staff of a nation has led his men into a battle, knowing well that not many would be able to come back. Such men are not born every day.

Brigadier Rajinder Singh was awarded the second-highest gallantry award of the nation, MVC, posthumously. His action, however, clearly deserved much more. It is also an irony that not a single man out of 100+ who died fighting against the odds was ever recognised or awarded. The injustice continues to the day!

(The author is a military historian and a Founder Trustee of the Military History Research Foundation, India.)

Trending Now

E-Paper