Harry Walia

“Indian painting would have been poorer if the art of Basohli had not existed” – Ajit Ghose

Storytelling is as ancient as time. Storytelling through art goes back than many contend. Bones, skins, rocks, walls, leaves, cloth, wood, metal, and paper have been the canvas of humans to visualise the stories of gods, love, war and their life. Miniature Paintings, which depict a cosmos shrunk by many scales, all in infinitesimal details, have been an integral part of this tradition.

“A miniature is meant to be held in hand and read closely” sums how BN Goswamy got into the heads of the artists and unravel the rich tradition of Miniature Paintings of India spanning some thousand years.

The delineation of Buddhist text (Asta Sahasrika, Prajnaparamita) on the fragile palm leaves, belonging to the reign of Palas in Eastern India and emulating the classical murals in Ajanta Caves that were ‘stumbled across’ in Western India, are the earliest known extant examples of Indian Miniatures (c 983 AD). Though they represent a technically mature style which had spread to areas including Nepal, Sri Lanka, South East Asia, any miniature painting ascribable to a date earlier has so far not been discovered.

In Northern part of the country, an independent Western Himalayan hill state of Basohli, formerly known as Vishwasthali, birthed a unique style of Indian Miniature Painting, and arguably the greatest of all, the traits of which are widespread in the adjoining hill states, mainly Mankot, Nurpur, Kulu, Mandi, Suket, Bilaspur, Nalagarh, Jammu, Chamba, Guler and Kangra.

What has been termed as the first mention of Basohli School of Painting is in a report of Archaeological Survey of India 1918-19, stating that Archaeological Section of the Central Museum, Lahore has acquired a few Basohli Miniature Paintings (called ‘Tibeti’ by the curio dealers around Punjab) and their curator has concluded from his study that the School is possibly of Pre-Mughal origin. This perplexed connoisseurs all over the world and they began delving into its history.

Since the subjects of these paintings are Nayakas and Tantrik Devis such as Durga, and use fragments of beetles’ wings for ornamentation, amongst other considerations, they are found to be the later works of the Basohli School and most likely from the period 1660-70 AD.

Ajit Ghose, India’s foremost art collector and critic, revealed he had begun collecting specimens of Basohli Miniature Paintings more than a decade before the report, some of which are clearly older than those in Lahore Museum, and represent a much older tradition. The antiquity of Basohli School of Painting as such, is clear.

Describing his collection of ‘Basohli Primitives’ as he termed them, Ghose has written, “The miracle of the descent of Ganga has the outstanding qualities of imagination and expressiveness. It is a real tour de force. The tremendous rush of the mighty, whirling torrent and the rolling, shimmering foam, have been painted with wonderful success. Behind the figures of Shiva and Parvati, on the left, slanting into depth away from the spectator is Mount Kailas, most curiously depicted, and the abode of God strangely suggested by a doorway. This man, in spite of all the crudity of his mode of expression, is a true artist. The same vigorous draughtsmanship and power of expression characterize the pictures of Durga slaying Mahishasura, Vishnu on Garuda, and the Flute of Krishna. Rama and Sita is a striking composition and a more accomplished drawing. It is, possibly, of later date.”

They combine an unexpectedly spirited delineation with a bold and even daring composition; represent the folk-art stage of the School, the oldest style of the purely Hindu Painting of Western Himalayas, and closeness to mural painting, he has determined.

At the first chance, the traders and art scholars classified Basohli Paintings under or with the Pahari, Jammu, Tibeti, Nepalese, Rajput, Rajasthani, Gujarati, and Mughal Schools of Miniature Painting. Such is the distinctive style of these paintings and their historical importance in the annals of Indian Painting tradition, that re-classification of the Indian Schools of Miniature Painting was strongly sought so as to establish a different pedestal of respect and recognition for it.

Balauria Rajputs bearing the surname Pal, are learned to have founded their state of Basohli around 8th century with Balaur or Vallapura as their original capital, mentioned first in the Rajatarangini. The history prior to Pals is still obscure.

From certain texts we gather that Raja Bhupat Pal was put into prison by his contemporary Raja of Nurpur, with help from Jahangir. He managed to escape from the prison after 14 years, defeated the Nurpur army and recovered his state in 1627. In 1635, he founded the present town of Basohli, and went to Delhi to pay his respects to Shah Jahan where he was assassinated, allegedly by the same Raja of Nurpur with the connivance of Mughals. Interestingly, few paintings of him in Basohli style are available.

In the existing knowledge of Basohli School, the reign of Bhupat’s son, Raja Sangram Pal (1635-73) stands out in the country for art patronage, bountiful creations and rejection of mughal influence. While there are reasons to believe that the indigenous style of Basohli was in practice even before him, not much has been done to establish it with evidences and narrative accounts.

It is well-known that the 17th century was a period of revival of Vaishnavism in Western Himalayas. Basohli, more so, was a sanctuary for Hindu culture and art.

In ‘Divine Pleasures: Painting from India’s Rajput Courts – The Kronos Collections’, Steven Kossak, an art curator, sings praises of ‘this brilliant school of painting that emerged as a beacon of traditional Indian aesthetics.”

He has ascertained in ‘Indian Court Paintings, 16th-19th Century’ that “in contrast to the assimilationist tendency of the Rajasthani ateliers, the workshops of Western Himalayan Hills turned their backs on Mughal influence. The Basohli idiom seems quite clearly to reject Mughal conventions in favor of a style solidly within the mainstream of indigenous Rajput tradition. These paintings mostly illustrate religious texts rather than embracing Mughal subject matter.” The artists, who migrated from other Schools of Paintings or fled from Aurangzeb’s rule for he despised art, also joined the Basohli workshops.

Through diversity of themes, years of execution, hands of the artists, or Rajas on the throne, there runs an underlying unity which makes the paintings part of the same school, and distinct from other Schools of Miniature Painting or their influences.

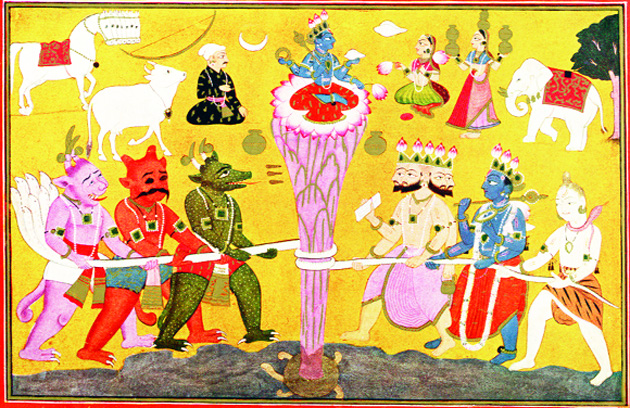

Apart from portraitures of various rulers and prominent persons of then, Basohli Miniatures have been painted around the themes of Hindu Pantheon, Rasamanjari, Ragamala, Krishna Leela, Ramayana, Tantric manifestations, and Gita Govinda, transcending different phases of evolution of the style though not exactly in the same order. Some of them bear shlokas and inscriptions in Takri for describing the painting and often artists.

The most remarkable and obvious features of this School are vitality, originality, unconventionality, depth of conviction, detailed execution yet considerable simplicity, lyrical intensity, sincerity of emotions, symmetry and unity of composition. The architectural designs; large effects, strong and symbolic colors; facial and figure types – receding foreheads, downwards continuing nose, large eyes, small mouths, receding chin and full cheeks; short choli, skirts, scarves, diaphanous draperies; pearl ornaments or white dots to represent pearls, beetles’ wings; natural poses and gestures, eloquent expressions, precisely painted every strand of hair, all enhance the aesthetics and attest to the amazing imagination of the artists and their mastery of the art.

Some artworks, out and out masterpieces, have come to light from the collections of prestigious museums, art galleries, palaces, workshops, and houses, in the hill states, rest of the country and across the world. In all likelihood there are many more waiting to be discovered.

Lamentably, the Basohli style which has no parallel anywhere, was gradually supplanted or mutated by Schools of nearby hill states and even the Mughal. “The chief proponents of this new idiom were two brothers, Manaku and Nainsukh, the greatest Pahari artists of the 18th century. Afterwards, it was very largely a continuation of their work by their children,” Kossak has suggested. It further waned under Muslim potentates, British Officers, and their sympathizers. ‘Art is never finished, only abandoned’ took a literal turn in this case.

The historical state of Basohli, the fountainhead of phenomenal art style and a centre of excellence, now merely a tehsil in Kathua district of Jammu province, has been forcibly shorn of its former glory, and its unique art tradition lost in the mists of time, Kashmir-centric politics and garbs of administrative reforms.

The successive Governments, political and societal honchos, have not only failed to explore, preserve, and promote this legacy, they have denied it the benefits of mere existence in their policies and initiatives. They have time and again publicly painted a sloppy and fallacious picture for the Basohli School.

One department, in particular, has gone to the extent of glossing the mughal influence on Basohli style and proclaiming that it was ‘started by mughals’ in the application for Geographical Indications Tag, the official process for which was started after years of beseeching. It is quite telling of the officials heading that department, necessitating an immediate remedy.