Sapna Sadhralia

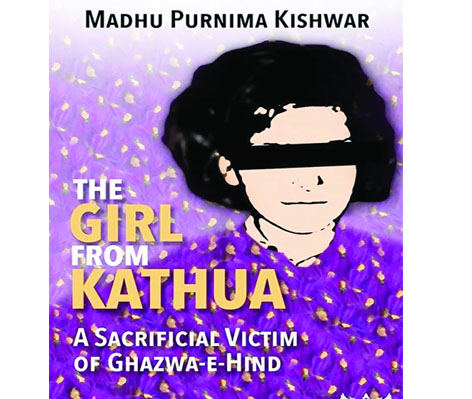

Title: The Girl from Kathua:

A Sacrificial Victim of Ghazwa-E-Hind

Author: Madhu Purnima Kishwar

Publisher: Garuda Prakashan Private Limited

Pages: 641

Language: English

Price: Rs. 799

As I perused Vineet Narain’s book on the ‘Hawala Scandal’ a decade ago, I was struck by his remarkable prowess in investigative journalism. At the time, I believed that no other author could surpass his abilities in this field. However, after reading Madhu Purnima Kishwar’s book, “The Girl From Kathua,” I must concede that it comes remarkably close to matching that standard. Kishwar’s thorough and penetrating investigation into the events surrounding the 2018 Rasana incident is a testament to her remarkable skills as a journalist and writer.

As Founder Editor of Manushi, a journal launched in 1979, Madhu Purnima Kishwar is widely acclaimed for having a uniquely Indic approach to gender, social and legal matters. From 1991 to 2016, she served as a Professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies. Before that, she taught at Delhi University College. Currently, she is a Senior Fellow at the Nehru Memorial Centre for Contemporary Studies, New Delhi.

The book is based upon the infamous incident where a minor nomadic girl from the Bakarwal community was found murdered in village Rasana, district Kathua of the erstwhile State of J&K in January 2018. Reportedly, the girl was kidnapped, kept inside a village temple and gang-raped and later murdered. After the initial investigation by the local police, the case was transferred to the J&K Crime Branch which produced a Chargesheet in Pathankot Court in April 2018 and a revised chargesheet thereafter. The Supreme Court had transferred the trial of the case from Kathua to Pathankot on a plea of the victim’s family. On June 10, 2019, a special court sentenced three people to life imprisonment while three others were sentenced to five years imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 50,000 each.

From the beginning, there was a massive outrage against the J&K Crime Branch which had allegedly investigated the case on communal lines with the ulterior motive to demean the Dogra community and demonize them as supporters of rapists, the author observes.

The book claims to expose the sinister jihadi designs of the PDP government led by Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti to persecute Hindus. The book has been written after putting painstaking laborious research into the incident for more than four years, during which Madhu Kishwar visited Rasana village and other places in Jammu region and took interviews to arrive at the conclusion. The writer states that the composition of SIT of the J&K Crime Branch was controversial and the investigation was conducted in an unprofessional manner. The author further explains that the chargesheet had multiple loopholes which were liable to be dismissed but the trial judge overlooked the defence’s arguments and passed an unfair verdict.

From the day one, there was a sense of disbelief about the case in me as I was well versed with the social fabric of Dogras, J&K bureaucracy and the stature of the political leadership of Dogras and their say in the policy-making. I made up my mind to follow the case since the day a reputed senior advocate of J&K High Court and the then Bar President B.S Slathia was humiliated by Arnab Goswami in his prime time show for calling the Crime Branch investigation as biased and botched up. Since then I closely followed the social media and local and national newspaper coverage of the Rasana incident.

The book addresses the girl as #GhazwaVictim instead of calling her Miss A or A**fa. The book is divided into 4 sections and 32 chapters, Section one initiates the ‘Kathua conspiracy and the bizarre charge sheet’ in which the writer has revealed the bare facts & trajectory of the case and mentions how she get involved in investigating the dynamics behind the #GhazwaVictim’s murder. Chapter 6 of Section 1 narrates the fake spoon-fed BBC reports on the incident. The writer has quoted a BBC report dated April 12, 2018, by a Srinagar-based freelancer stringer published under the caption “A**fa B**o: The Child rape and murder that has Kashmir on edge.” The writer has argued that neither the victim was a Kashmiri nor the killing had taken place in Kashmir then how come Kashmir was on the edge? She further questions whether the BBC would have reported similarly had a girl from the Hindu religion in Jammu or Uttar Pradesh been murdered. The writer states that BBC’s stance on the case was quickly adopted by almost all national and international magazines and TV channels. Barring Zee News, all Indian papers and TV channels followed the BBC template through spoon-fed reporting of the case. However, the writer agrees that some Hindi newspapers with active bureaus in Jammu did try to present more factual reporting, but by and large, none dared to boldly expose the officially-peddled lies.

The writer further points out that the title of the report carries not only the name of the alleged rape victim but also her picture, which goes against BBC’s code of ethics. Not only this, even CM Mehbooba Mufti in her initial tweets revealed the victim’s name and humiliated the opposing Hindus. As CM and Home Minister, she had effectively pronounced judgment on the accused and steered the investigation onto a sinister communal course.

Chapter 7 of Section 1 deals with the arrest of the sole juvenile accused and the roping in of other persons including the alleged “Mastermind”. The writer says that in January 2018 police proudly announced that they had cracked the case following the arrest of a juvenile accused even though the police had zero evidence to back their claim. Since most people in the region did not know who the juvenile accused was, there was no mass outrage at his arrest. It was only when Sanji Ram was implicated along with seven others–with police shifting the scene of the crime from an innocuous cowshed in Rasana to the Baba Kaliveer Devasthan in the same village–that spontaneous protests arose in various districts of the Jammu province.

In Section 2, the writer exposed the lead players who orchestrated a fake narrative for the media.

In Section 3, the writer questioned the pretentious judgment pronounced by the trial judge and exposes his compromised credentials. In Chapter 24 of Section 3, the writer points out that crucial witnesses were dropped during the trial and dubious witnesses were brought at the eleventh hour. A crucial ‘last seen witness’ was dropped, and a crucial witness who led the dog squad was also dropped.

Of all the 32 Chapters in the book, I found Chapter 25 of Section 3 intriguing in which the bare facts exposed the falsity of the crime branch’s report. The writer states that the most damning part of Sessions Judge’s judgment was the reluctant acquittal of Vishal Jangotra, the younger son of Sanji Ram who had to be acquitted because Zee News had managed to procure CCTV footage of Vishal’s presence in Muzaffarnagar on the very same day he was alleged to have committed the gang rape and joined the murder of little girl. The writer states that the evidence put forth by the J&K police to implicate Vishal Jangotra was concocted and cast a heavy shadow of doubt on the rest of the yarn they had woven to implicate Sanji Ram and six others and the alleged chain of events collapsed following Vishal’s acquittal. In Section 3, the writer states that if the victim’s case had come up before an upright judge, he would have at least ordered a reinvestigation into the case by an independent agency.

In the conclusion of the book, the writer discusses the 2009 Shopian murder and alleged rape of two Kashmiri women in which Mehbooba Mufti had rejected the J&K SIT probe and demanded a CBI investigation into the incident.

The language throughout the book is simple, fact-based and backed up by maps and screenshots for easy understanding by a common reader. The book is a must-read for anyone interested in investigative journalism. The number of pages is on the higher side and the book is priced at a premium. A Hindi version of the book is much needed.

Trending Now

E-Paper