Chauncey K. Robinson

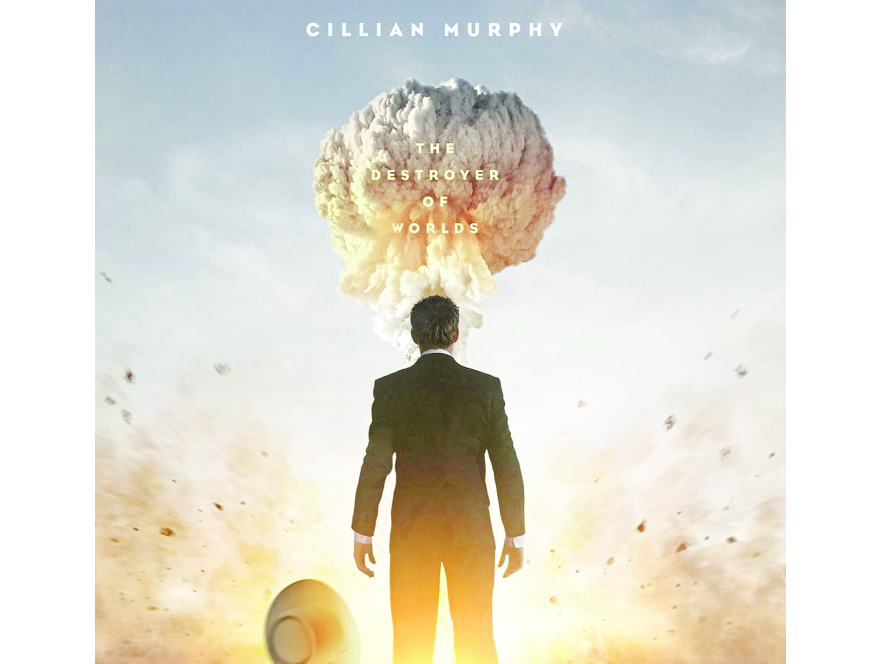

The existence of a film like Oppenheimer shows just how necessary it is to teach history in all of its complexities and nuance. When tackled in a way that is not sanitized, it can open up a true exploration of our past and its influence on our present and future. This biopic explores the life of the “father of the atomic bomb,” Julius Robert Oppenheimer, portrayed on screen by Cillian Murphy. The film masterfully creates an engrossing and dramatic thriller that intertwines history and questions of morality. It takes a deep dive into the Atomic Age of the 1940s and forces viewers to grapple with questions of how the period forever changed the course of human history. It is a heavy three hours to sit through, but well worth the viewing.

Written and directed by Christopher Nolan (Dunkirk), Oppenheimer is based on the 2005 biography American Prometheus, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. The film tells the story of theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who was pivotal in developing the first nuclear weapons as part of the Manhattan Project, thereby ushering in what has been called the Atomic Age.

The Atomic Age began when the first nuclear bomb—called “The Gadget”—was tested in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, during World War II. The bomb’s success would lead to the atomic annihilation of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki near the end of the war. It represented the first large-scale use of nuclear technology and brought about immense changes and divisions regarding technological development.

Oppenheimer played a pivotal role in launching this era. His scientific genius and organization of the Manhattan Project brought about one of the most influential scientific breakthroughs known to humankind. This breakthrough, of course, was a double-edged sword, as the theoretical scientist had to deal with the fallout (literally and figuratively), the lives lost, and the potentially catastrophic future his bomb could bring. The film explores Oppenheimer grappling with this moral dilemma, the atmosphere that brought about his conviction to create the bomb, his misgivings after the bomb came to fruition, and the influential figures around him that helped in his rise, fall, and eventual rise again in the public eye.

What the film also makes plain is that politics cannot be separated from how science and innovation are used to either help or hinder humanity. Director Nolan doesn’t shy away from the politics that shaped Oppenheimer’s life and those closest to him. Like many in the 1930s who were radicalized by the hardships of the Great Depression and the global rise of fascism, Oppenheimer was an individual who leaned heavily towards left-wing political thinking.

His lifelong best friend was a member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA); his brother Frank was a former member of the party; one of his first great loves, Jean Tatlock, was a member of the CPUSA; and his eventual wife and the mother of his children—Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer—was also an activist and former member of the CPUSA. For a good chunk of Oppenheimer’s life, he donated to a number of causes that would soon be deemed “radical,” “socialist,” and “communist.” By his own account, he subscribed to People’s World and was “quite close to the Communist Party,” though he never officially joined.

It is essential to understand the socio-political context of Oppenheimer’s life in order to grasp the treatment and red-baiting he endured as he began speaking up against the U.S. government’s use of science and innovation to fuel war and militarism.

Due to the intertwining topics and themes, Nolan goes the route of not telling Oppenheimer’s story in a linear way. The focus is on three key points in history for the scientist. The first is his early days leading up to being recruited for the Manhattan Project and his time working on it. This is where the audience gets a glimpse into his psyche and the scientific, political, and personal factors that influenced him. We see his connections with labor organizers attempting to unionize the professors and staff at UC Berkeley. We also learn that the FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, had begun surveilling Oppenheimer even before WWII.

The second segment is centered on the panel hearing he endured in 1954 that led to his government security clearance being revoked. This is perhaps the heart of the film, as we see Oppenheimer grappling most with his legacy and his role in the creation of such a powerful weapon. This is the hearing that brought about his “downfall,” the moment when his “loyalty” to the government was questioned due to his past political affiliations and his opposition to certain projects the government was pushing—like the catastrophic hydrogen bomb.

The third key point follows Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss (played to perfection by Robert Downey, Jr.) years after Oppenheimer’s clearance was revoked. Strauss had played a central role in stripping Oppenheimer of his clearance. The portion of the film is set during Strauss’ Senate confirmation hearing to become Secretary of Commerce under then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower. This may seem like a random point for some not familiar with Strauss’ frenemy relationship with Oppenheimer, but it plays a pivotal role in driving home the fact that although Oppenheimer was a crucial ingredient for many scientific advances in his era, he—along with characters like Strauss—were also a puzzle pieces in a larger political picture. Strauss had been chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, advocated for the hydrogen bomb, and minimized the impact of radiation fallout on Pacific Islanders affected by U.S. nuclear tests.

This all may seem like a lot for a film to take on, but it works. Nolan embraces the complexities of his main character and all the supporting characters around him. It is this embrace of complexity and nuance that lends itself to not shoving anything into a particular box, but rather allowing the audience to make the connections and form their own conclusions. Murphy helps bring it all together in an inspired yet reserved performance.

Other characters who stand out in their own right are Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty (played by Emily Blunt) and the scientist’s former girlfriend, Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). Blunt gives a chilling performance as the loyal and somewhat troubled wife; it is this critic’s hope that the film encourages viewers to look deeper into Kitty’s life to understand her history in the progressive movement even before she met her husband. Hers is an interesting tale that Nolan touches upon briefly, but it helps viewers grasp the character’s choices and attitudes which those unfamiliar with her past may initially find perplexing. Pugh’s Tatlock makes a lasting impression in the film, although her presence feels all too brief.

What the film also explores through its look at Oppenheimer’s life is the use of science and innovation by the government and the volatile dynamic that can result. U.S. government officials knew of Oppenheimer’s ties to left-wing groups and people, yet they understood the importance of his potential contribution. This was true not only for Oppenheimer, as many of his colleagues—a number of whom worked with him during the Manhattan Project—were later blacklisted during the red-baiting witch hunts of the McCarthy era.

Oppenheimer was allowed to take on an advisory role in government, but the rapid development of potential world-ending weapons left many in the scientific community conflicted. Working for the government on such projects left them with no real ownership over how their research discoveries were used. Oppenheimer was one of the few allowed to speak out and disagree, even as he continued to advise the government, due to his star power. Yet, his security hearing—where his political affiliations were targeted and his clearance denied—marked a dark day when censorship and oppression won out.

Talented people were pushed out of their careers because they dared to question the state and the socio-economic system. The blacklisting happened not only in the scientific field but also in entertainment, medical, and other industries. Who knows what innovations might have been lost to time due to the oppressive McCarthy era? The weight of these blacklistings isn’t lost on director Nolan, either, as he takes moments to acknowledge those around Oppenheimer who were also affected.

Once again, there’s a lot here, yet Nolan manages—through dynamic storytelling and highly imaginative directorial choices—to infuse an energy in the film that prevents it from ever feeling like a three-hour slog. That’s pretty impressive when you’ve got to relay the complexities of theoretical physics to audiences who may have never tried to understand the topic before watching the film.Oppenheimer is a must watch for those who love history and good story telling in general. (IPA)

Trending Now

E-Paper