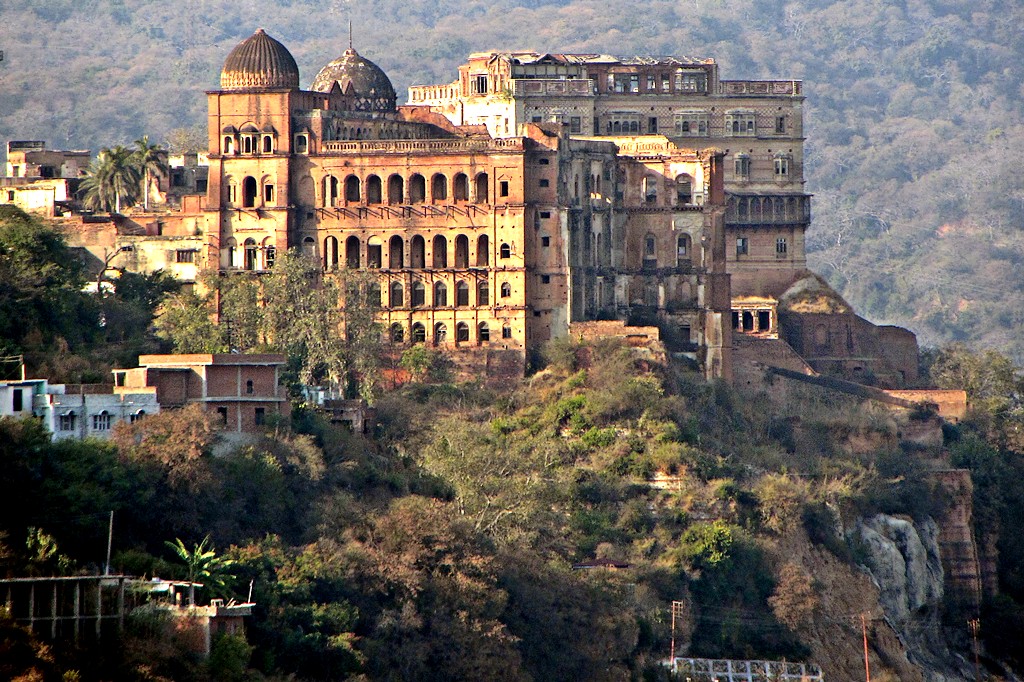

The historic Mubarak Mandi Complex in Jammu stands as a testament to the rich cultural heritage and architectural splendour of the Dogra dynasty. Despite its historical significance, the complex has long struggled under the weight of neglect and bureaucratic inertia. However, recent developments signal a promising shift towards its restoration and preservation. The decision to transition funding from the Languishing Projects Scheme to the Capex Budget, coupled with the establishment of a dedicated Engineering Wing, marks a pivotal moment in the efforts for restoration. The previous scheme, while well-intentioned, often resulted in inconsistent fund allocation, impeding steady progress. The Capex Budget, however, promises a more reliable and streamlined financial flow. The provision of Rs 40 crore for the current financial year, out of a total of Rs 140 crore earmarked for the project, underscores the Government’s commitment to the restoration.

One of the most pressing challenges in the restoration of Mubarak Mandi has been the lack of specialised manpower. Previously, only a handful of engineers from the Tourism Department were assigned to oversee the project, leading to inevitable bottlenecks and slow progress. The establishment of a dedicated engineering wing from the R&B Department is a crucial development. This division, now focused almost exclusively on Mubarak Mandi, brings much-needed expertise and attention to detail, ensuring that the restoration work is both meticulous and timely.

However, despite its declaration as a State Protected Monument and numerous restoration efforts, the Mubarak Mandi Complex remains largely unrestored. The formation of the Mubarak Mandi Heritage Society and the announcement of a detailed master plan in 2019 with clear timelines and work details were promising steps. However, five years have passed with little visible progress. Instead of focusing on restoring one palace at a time, the Heritage Society began work on all the front palaces simultaneously, without adequately considering the budget and the need for expert manpower. Consequently, all the front palaces, except those restored by the Archaeological Survey of India, are without roofs and continue to suffer from rain and other natural calamities year after year. Moreover, no efforts have been made to reinforce the back side of the complex as suggested in the master plan.

With the new initiatives taken by the administration, one hopes the mega heritage structure gets proper attention now and will be restored within the set new timeline. Now, the restoration plan prioritises five main buildings within the complex: Raja Ram Singh Palace, Dogra Art Museum, Army Headquarters, Darbar Hall, and the Central Courtyard. A three-year timeline (2024-25 to 2026-27) has been set for the completion of physical restoration and the adaptive reuse of these structures. DPRs for these buildings have already been prepared. The adaptive reuse of these buildings, once restored, will be a critical aspect of the project, ensuring that these historic structures are not just preserved as static monuments but are integrated into the cultural and social fabric of contemporary society.

Given past experiences, the recent restructuring of the engineering wings across different departments has been a strategic move to enhance efficiency. The Government has addressed two major issues: consistent funding and specialised manpower. This restructuring, combined with the shift of administrative control from the Tourism Department to the Culture Department, reflects a more cohesive approach to heritage conservation. The engagement of a Conservation Architect, with expertise in the restoration of heritage sites is another positive step, ensuring the highest standards of conservation. The Heritage Society needs to accelerate the restoration efforts.Timely completion of the project can ensure that Mubarak Mandi remains relevant and accessible to future generations.

Trending Now

E-Paper