Pushp Saraf

The tale of two trans-Himalayan districts, Leh and Kargil, is one of complex politics, simmering tensions and a constant struggle for identity. Together, these districts form the Union Territory (UT) of Ladakh. Their history of coexistence spans several eras: first as part of the Ladakh kingdom, then under Dogra rule and later as part of the same Leh district until 1979 when Kargil was designated a separate district. This division continued under the short-lived Ladakh Division of the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir in February 2019. Even while remaining distinct districts they were collectively transformed into a UT without a legislature on October 31, 2019.

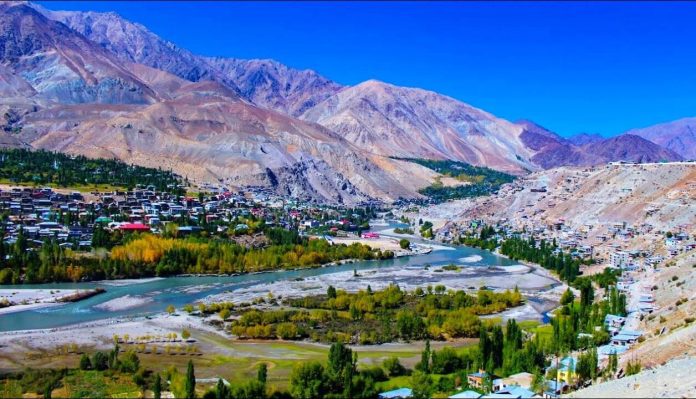

A notable difference between the two districts was that Kargil often played a subordinate role. Even as a separate district, Kargil struggled for recognition. Although geographically part of Ladakh, it was largely overshadowed by Leh. Ladakh was commonly identified with Leh, particularly Buddhist Leh, which boasted prominent Buddhist leaders, imposing monasteries and stunning natural beauty. Leh remained in the spotlight for a long time, partly due to its late spiritual leader Kushok Bakula’s close relationship with the country’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru chose Bakula for a political role which he fulfilled with great responsibility. Bakula earned a reputation as a statesman.

In contrast, Kargil did not enjoy such advantages. As a Shia Muslim majority area, it looked more towards the Kashmir Valley with which it shared religious proximity.

Three significant developments in 1989 jolted Kargil and underscored the need for a stronger and more cohesive identity. The first was the outbreak of separatist violence in the Kashmir Valley. Despite Kargil’s close religious and political ties with Kashmir, it did not share the secessionist sentiment and reaffirmed its commitment to national unity by actively participating in elections.

The second development was the social and economic blockade of Muslims imposed by the powerful Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA) in Leh, as part of their struggle for UT status. Kargil distanced itself both from the Valley’s violent separatist movement and the LBA’s aggressive stance, which had anti-Sunni Muslim undertones.

The third major event, from the perspective of Shia Muslims, was the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of the Iranian Revolution. His passing had a profound emotional impact on the Shia community, as the revolution had awakened their awareness of their potential as an independent and influential force.

These events collectively heightened Kargil’s awareness of the need to safeguard its own interests. The realisation dawned that situated between the Valley and Leh, each pursuing their own agendas, Kargil needed to assert itself to protect and promote its unique identity.

This sentiment manifested in the 1989 Lok Sabha elections when, for the first time, a Shia leader from Kargil, Mohammad Hassan (popularly known as Commander), won the seat from the Buddhists of Leh by defeating the Congress stalwart P. Namgyal. This was a momentous political event. One key factor in Commander’s victory was the strong support from the National Conference (NC), which opposed the Ladakh Buddhist Association’s (LBA) demand for separation from Jammu and Kashmir. Although Namgyal was not an LBA activist, he, like many of his party colleagues in Leh, had aligned with the LBA’s popular stance. The NC never publicly acknowledged its role in his defeat given its electoral alliance with the Congress.

In 2024, however, Kargil made a powerful and unequivocal statement in the Parliamentary elections. The local leadership of the National Conference (NC), led by Qamar Ali Akhoon, openly defied the party’s directive to support Congress candidate Tsering Namgyal. This bold move was unprecedented compared to 1989. In a remarkable show of unity, the local units of the NC, Congress, and other parties, except for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), rallied behind their common candidate Haji Mohammad Hanifa Jan securing his victory.

Meanwhile, the Congress and BJP both fielded Buddhist candidates which split the Buddhist vote in Leh and diminished their chances. The BJP, instead of re-nominating their former one-time poster boy Jamyang Tsering Namgyal, chose Tashi Gyalson, Chairman and Chief Executive Councillor of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC, Leh). It appeared that both the Congress and BJP were more focused on preparing for the upcoming Council elections in Leh in 2025 rather than the immediate Parliamentary race!

This does not imply that Leh has lost its prominent position. Historically, it has fought all its battles independently. The Lok Sabha election might have been more competitive if the newly-elected LBA, whose election coincided with the last date for candidate withdrawals, had had the opportunity to mediate and reconcile the differences between the BJP and Congress.

Any impression that Leh and Kargil have bitterly fallen apart is misplaced. In fact, they remain united in fighting larger battles such as seeking statehood for Ladakh and its inclusion in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. The Apex Body of Leh and the Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA), which include all political and religious groups from their respective districts, are jointly leading this agitation. The overall structure remains intact. All that has happened is that its two supportive districts are more balanced, with Kargil strengthening its position. The Apex Body and the KDA have also resolved a 50-year-old controversy regarding the construction of a monastery in Kargil, with Thupstan Chhewang, Qamar Ali Akhoon and Asgar Ali Karbala playing decisive roles.

Trending Now

E-Paper