By Nilanjan Banik

Kaala Pani, a web series on Netflix is a gripping tale about the outbreak of a lethal disease and a deadly health epidemic creating an atmosphere of chaos and fear. What makes the storyline more interesting is that it tests the ability of the administration to contain the spread of the disease among the residents and hundreds of tourists gathered on an island for a big festival. What if such an incident becomes a real one?

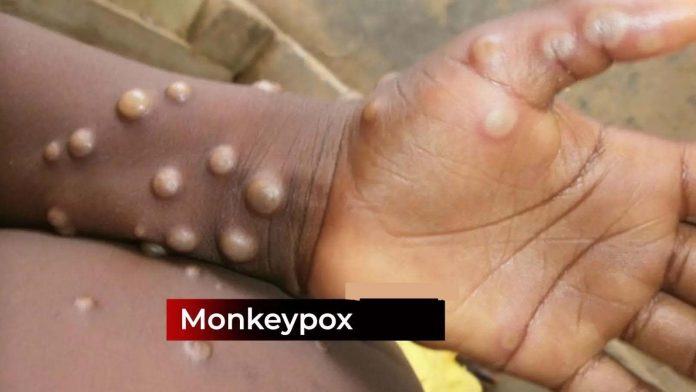

Going by the World Health Organization (WHO) there is a high probability of another pandemic coming soon. In fact, now we have rapid spread of M pox virus, formerly known as Monkeypox virus. According to the WHO, M pox has been declared a “public health emergency of international concern.” The current outbreak has been driven by Clade 1 strain of the M pox virus, which is more virulent and capable of spreading through skin-to-skin contact. This makes it particularly dangerous for low-income countries with dense populations.

No wonder, the spread originated from the African continent, with fourteen countries already impacted. Outside the African continent M pox is reported in four countries, namely, Sweden, Thailand, the Philippines, and Pakistan. In India Kerala reported two cases of M pox in March this year.

Presently, there are 8 families of viruses in the WHO priority list, each one mutating in an unknown way and becoming more virulent because of climate change, which may lead to the occurrence of deadly disease such as this more virulent version of M Pox. WHO has already floated a concept called Disease X (akin to the virulent version of M Pox), to understand the future readiness of any country to fight the pandemic. M Pox has symptoms similar to COVID-19, including cough and flu-like symptoms, along with lesions filled with pus. It is to be noted COVID-19 killed 6.9 million people.

How much prepared is India? In a counterfactual analysis, we identified the factors that influenced the preparedness of Indian health professionals and policymakers when the second wave of COVID-19 struck India. Back then, COVID-19 was more like M Pox, a pandemic that tested the preparedness of India to fight the pandemic. There was a shortage of hospital beds and doctors. Disruption in the medical supply chain impacted the availability of medicines, vaccines, PPE suits, and ventilators. There were erroneous policy decisions, such as the government’s hasty decision to implement a nationwide lockdown without providing adequate lead time for migrant workers to return to their native places.

In this paper titled, Need for Policy Reforms in the Aftermath of COVID-19?, we took a detailed look at all possible factors leading to disruption in medical facilities leading to higher death count. When an outbreak of disease occurs suddenly, it is crucial to address three main factors: operational, financial, and logistical issues. Among operational issues, lack of cooperation and collaboration among multiple stakeholders including public health officials, government agencies, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and distributors were reasons for a broken medical supply chain. Public health is a state subject in India. However, it is the Government of India that is responsible for designing health policies. During a viral outbreak, there is often a mismatch between the number of vaccines or medicines available at the federal level and the demand at the state level.

There were also logistic issues. For instance, people were unwilling to take vaccines due to fear emanating from a lack of trust, side effects, and concern regarding the efficacy of the vaccines. In addition to these demand-side factors, there are also supply-side issues. For instance, RT-PCR testing facilities are seldom available, particularly in rural India. This led to patient inconvenience, delay in getting test results, resulting in hesitancy on the part of the people to get the testing done.

Among the financial issues, although tariffs resulted in an increase in the price of medicines and vaccines, it is the non-tariff measures that were responsible for supply chain disruption. During the time of Covid-19, the higher price of Chinese active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) was negatively impacting the supply of medicines. In comparison to the pre-COVID days, Chinese suppliers of APIs and para amino phenol (used for manufacturing paracetamol) increased prices by 20% and 27%.

Preemptive policy measures aimed at promoting a healthy population may also be beneficial. In India, over 80% of all non communicable disease (NCD)-related deaths in India are attributed to four major diseases: cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes. COVID-19 has demonstrated that fatality rates are higher among individuals with co-morbidities.

Can government adopt policies that can reduce co-morbidity? Smoking is a major cause of cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and cancers. Tobacco-related cancers accounted for nearly half (48.7%) of the cancer burden in 2021. Given the challenges of quitting smoking—where only about one in ten adults who smoke succeed—could there be a less hazardous alternative? For instance, the government could reduce taxes on products that are less harmful than cigarettes, such as nicotine patches, nicotine gum, nicotine lozenges, and nicotine inhalers. This approach could make these alternatives more accessible and encourage their use over traditional smoking.

To enhance our health policy’s effectiveness, whether in combating future mutant deadly viruses or addressing existing diseases leading to co-morbidity, it is crucial to increase awareness within policy circles about approaches that are most effective. There is a need to establish an independent task force comprising of specialists, including doctors, economists, pharmaceutical executives, and engineers. This task force would provide valuable input, potentially through a real-time Integrated Health Information Platform, reflecting the problems in the existing set up and policies. (IPA