The Supreme Court’s dismissal of a petition to revert to ballot paper voting in India marks an important moment in the ongoing debate about the evolution of electoral systems. The plea, which also sought stringent measures to curb election malpractices, was reflective of growing apprehensions about the sanctity of elections in the digital age. Yet, the Court’s rationale for rejecting the plea was grounded in pragmatism and the need to embrace technological advancements while addressing underlying issues of corruption and transparency.

EVMs have been at the centre of elections since their phased introduction in the 1990s. They were heralded as a solution to many issues associated with paper ballots, including logistical challenges, slow vote counting, and rampant tampering. However, scepticism over EVMs has persisted, often amplified by allegations of manipulation from losing candidates. The Supreme Court bench aptly pointed out this paradoxical trend: EVMs are only questioned when a party loses, not when it wins. This observation strikes at the heart of the trust deficit in India’s electoral system-not one rooted in the technology itself but in the political culture of contesting outcomes. Claims of EVM tampering, while sensational, lack empirical backing. The Election Commission has repeatedly emphasised the rigorous testing and safeguards in place for EVMs, including the introduction of VVPAT systems to enhance transparency. These measures provide a paper trail for every electronic vote, ensuring accountability and addressing concerns about electronic manipulation.

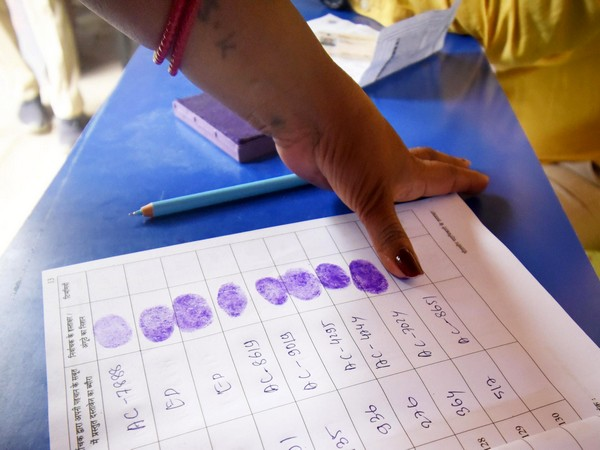

Advocates for a return to ballot papers argue that the traditional method is more transparent and less susceptible to tampering. However, history suggests otherwise. Pre-EVM elections in India were marred by booth capturing, ballot box stuffing, and prolonged counting processes that often led to disputes and violence. The logistical challenges of transporting, storing, and counting millions of paper ballots in a country as vast as India are staggering. Moreover, reverting to ballot paper voting would not address the core issue of electoral corruption. The petitioner’s emphasis on EVMs as a root cause of election malpractice overlooks systemic issues such as money and material inducements to voters-a problem that persists regardless of the voting mechanism.

The petitioner’s plea also sought a directive to disqualify candidates found guilty of distributing money, liquor, or other inducements to voters. This aspect of the petition highlights a genuine concern. Election malpractice, particularly the use of financial incentives to sway voters, undermines the very essence of democracy. The ECI’s efforts to curb such practices, including monitoring election expenses and seizing illegal cash and goods, are commendable but insufficient. The staggering figure of Rs 9,000 crore seized in 2024 alone underscores the scale of the problem. To combat this menace, stricter enforcement of electoral laws, real-time monitoring, and the use of advanced surveillance technologies are imperative.

Rather than reverting to outdated methods, the focus should be on leveraging technology to enhance electoral integrity. Blockchain-based voting systems, for instance, could provide an even more transparent and tamper-proof alternative to EVMs. These systems, coupled with biometric authentication, could eliminate many of the vulnerabilities associated with traditional voting methods. Additionally, the ECI must prioritise building public trust in EVMs. Transparent communication, regular audits, and involving independent experts in the process can help dispel myths and misinformation. Civic education campaigns are equally important to ensure that voters understand the system’s robustness and do not fall prey to politically motivated narratives.

India’s democracy is its greatest strength, and safeguarding its integrity is a shared responsibility. While the Supreme Court’s dismissal of the plea to revert to ballot paper voting was justified, it should not mark the end of the conversation on electoral reforms. The real challenge lies in addressing systemic corruption, enhancing transparency, and fostering trust in the electoral process. As the world’s largest democracy, India is leading by example, demonstrating how technology and tradition can coexist to uphold the values of free and fair elections.

Trending Now

E-Paper