Maneka Gandhi

The contents of your intestines are vital for your health. Within the intestine live trillions of organisms known as the gut microflora. Their many functions include: completing the digestion of foods through fermentation, protecting against disease causing bacteria, synthesizing water soluble vitamins, and stimulating development of the immune system. The health of the flora changes according to your diet.

Approximately 28 feet of digestive tube, known as the gut and intestine, processes food into life giving nutrients. The first 23 feet, which include the mouth, oesophagus, stomach, and small intestine mechanically divide the foods we eat, mix them with digestive enzymes, and then break them into microscopic particles ready for absorption into the body. The last 5 feet, known as the large intestine, or colon, works as a microbial factory. More than 400 different species of bacteria have been identified living in a single person. Within the colon their concentration reaches a trillion per millilitre of faeces. In a typical meat/milk/white flour eater one-third of the dry weight of the faeces is bacteria. For hose that eat healthily this concentration is less due to fibre in the diet.

The remnants of the foods we eat become the foods for the microflora. Different bacteria live better on different sources of nutrients. Gut microbial profiles are increasingly of interest to doctors and researchers as we begin to understand how they are linked to specific diseases. Scientists have already reported how microbial populations in the gut are different between obese and lean people and that when obese people lost weight their microflora reverted back to those found in lean people.

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that stimulate the growth and activity of “friendly” bacteria already present in your intestine. They are the preferred foods of “friendly” bacteria. The most effective prebiotics identified are small carbohydrates that are found naturally in artichokes, onions, chicory, garlic, leeks, and to a lesser extent, cereals. Many “friendly” bacteria secrete antibiotic substances that are active against harmful organisms.

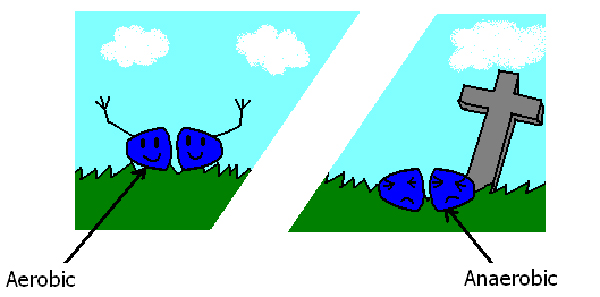

Vegetarians have higher counts of aerobic bacteria (bacteria that can live in the air) and lower counts of anaerobic bacteria (that can live and grow in the absence of oxygen) than meat eaters (Journal of Nutrition 105:878, 1975). Most importantly, the gut microflora of meat-eaters contains greater amounts of “unfriendly” bacteria that do unhealthy things to the body. A vegetarian diet promotes the growth and activity of “friendly” bacteria.

“Friendly” bacteria protect us from cancer in many ways. They have the ability to bind and deactivate cancer-causing substances in our foods. For example, Lactobacilli absorb cancer causing chemicals known as pyrolysates that are produced by cooking meat at a high temperature. These chemicals are deactivated when absorbed into the bacteria’s cell walls. “Friendly” bacteria also actively degrade cancer causing substances, like N-nitrosamines. Bifidobacteria produce antitumor substances that cause the human white cells to destroy growing tumour cells. A vegetarian diet decreases excretion of bile acids and the metabolism of these acids into cancer causing substances. A meat based diet causes bacteria to grow that make animal proteins into neutral sterols that are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. Research shows that a change from a mixed diet to a vegetarian diet leads to a decrease in certain enzyme (beta-glucuronidase, beta-glucosidase, and sulphatase) activity known to increase the risk for colon cancer.

Bile acids are produced by the liver for the purpose of digesting fats. The more fat consumed the more bile acids flow into the intestine to be converted to sex hormones which are then absorbed through the gut wall and into the blood stream (Lancet 2:472, 1971). Problems from excess sex hormones include: precocious puberty, fibrocystic breast disease, PMS, uterine fibroids, prostate enlargement, and breast, uterine, and prostate cancer. By changing the microflora with a low-fat, high-fibre vegetarian diet the sex hormones are excreted in the faeces, resulting in sex-hormone related problems being prevented and improved.

A vegan diet has been shown to change the faecal microflora in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and these changes are associated with improvement in the disease activity (Br J Rheumatol 1997 36:64, 1997).

Microbes in the gut change the trillions of microbes living in the gut, according to scientists writing in the journal Nature. The change happens quickly some within two days . One type of bacterium that flourishes under the meat-rich diet has been linked to inflammation and intestinal diseases in mice.

In a study done by researchers at Duke, Harvard University, Boston Children’s Hospital and the University of California, ten volunteers went on two different diets for five days each. The first diet was all about meat and cheese.

Then, after a break, the volunteers began a second, fibre-rich diet based on plants, grains and fruit. The volunteers’ microbacteria was checked before during and after each diet. The effects of the meat and cheese were immediately apparent. After the volunteers had spent about three days on each diet, the bacteria in the gut changed their behaviour. The kind of genes turned on in the microbes changed in both diets.

In particular Bilophila microbes started to dominate the volunteers’ guts during the animal-based diet. Bile helps the stomach digest fats. So people make more bile when their diet is rich in meat and dairy fats. A study last year found that an increase of Bilophila cause inflammation and colitis in mice. This finding supports other studies that prove the link between animal fat, bile acids and an increase in growth of microbes that may affect the risk of inflammatory bowel disease, the researchers said.

As soon as the diet became vegetarian there was an increase in bacteria called Firmicutes, which break down plant carbohydrates. The findings suggest “the choices that people make on relatively short time scales…could be affecting the massive bacterial communities that live inside of us.”

One thing is becoming clear: The bacteria in your intestine influence many aspects of your health, including weight, immunity and perhaps even behaviour.