Dr Mohinder Kumar

Migratory settlement of Kharnakling ‘Rabo’ colony is located near Choglamsar, 8 km from Leh. This settlement is home to the migrants of Kharnakzara, Samad Rukhten and Kurzok. These nomadic tribes were forced by natural and other circumstances to migrate from Changthang (90% from Nyoma block and 10% from Sham village in Nubra block). They migrated to survive under duress, between 1985 and 1995 by crossing Thang-lang-la pass on horse-back.

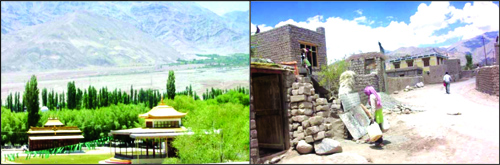

In Changthang these migrants used to be in regular nomadic mobility and move from place to place since generations; in Leh now they wander for casual wage-labor livelihoods. They are yet to decide whether old nomadic life of mobility was better, or the present life of vagabond-wage-wanderers is superior. Their lives are still trapped in transition from tribal to modern ways of life. This period of transition is the most difficult phase of their life. Kharnakling migrant settlement spreads from Tashi Gatsala to Tshe Manla. Its area is 30 acres, plain, residential, and without farming or pasture land, of which 14 acres was allotted by Revenue Department and remaining 16 acres is occupied/ expanded outside legal allotted area.

Village Weekly

The settlement has 170 households, a large number, considering that all are erstwhile nomads. They are Buddhists and retain social caste status of Scheduled Tribe (ST). They speak Ladakhi language. Both tribal migrant households and village non-nomadic households speak Ladakhi. Ladakhi language, like Buddhism, appears to be a strong binding factor of Ladakhis. Muslims in Ladakh also often speak Ladakhi language. It means Ladakhi language is not religion specific but people-geographic-region specific as it ensured harmony and social compactness of Ladakh area -a real symbol of unity of three great communities of Muslims, tribal nomads and the urban.

They reported that migration occurred due to three reasons: (a) extraordinarily heavy snowfall (5-7 feet) in Changthang; (b) no connectivity for six months; and (c) struggle with snow-clad cold nights. All of a sudden snow becomes a symbol of suffering and difficulties causing displacement though snow anyway troubled generations of Rabo nomads for hundreds of years. Migrants also refer to scarcity of grasses (for goats) and food (for family) though it may not be a sufficient reason to explain mass migration. It is difficult to establish any single reason. The issue of migration may require holistic analysis. What dominant factor triggered migration? Why migration did not continue but rather got stopped?

It is not that these erstwhile Rabo nomads do not have any skills, talents, crafts, trades or abilities. Post-migration, they could not utilize or showcase, in new setting, their traditional skills like yarn making, weaving, knitting, hide making, leather stitching, etc. carried from one generation to another, which could have been prospectively useful in their tryst with modern society. They could not capitalize on past skills, leading to their being erroneously termed as “traditional people without modern skills”.

Migrants are imbued with skills to compete economically but their chosen/ forced mode of living portrays them as traditional community devoid of skills. Majority (80%) of the migrants do wage-labor on whatever work they happen to find. After migration, works like leveling/preparing land, constructing kutcha house, molding earth, menial jobs -with contractor, on highway, on house construction site, and casual labor without tied to contractor, loader’s (“Kuli”) work and unskilled wage-labor, etc. characterizes their pattern of livelihoods. Only 20% migrants have adopted jobs like small shop, business, trade (grocery, wool collection & selling), taxi operator, driver, tourist-guide, guide-cum-driver, contractor, etc. Ironically erstwhile Rabo nomads who never owned-constructed house in the past are now called “contractors” in constructions and some are “labor contractors”. They turned into labor-contractors job since they know better than anyone else where wage-labor wanderers reside and could be sourced for wage-labor i.e., their new ‘avtar’ within present life-time in Leh. Migrants seem to be happy as wage-laborers. They work for six months (summer) and live relaxed life for 6 months during winter snow. Wage labor of six months would fetch income up to Rs.32000 per person. Average four persons do wage-labor in each migrant household. So, total wage income per family is Rs.1.28 lakh. Entire income is spent on household needs with no net savings. Migrants tell they are fine as money-spinning wage-wanderers in Kharnakling-Leh as compared to wool-spinning mobile nomads in Kharnakzara, if money is the criterion of life’s means for survival.

After 1985, Rabo migrants had to choose between their past and the present. If they chose past, they would be required to return to their roots. If they chose present, they would be expected to forget past. They are prepared for none. They cling to both past and present. By mid-1990, extension and continuation of life in Changthang had become disoriented. They started showing signs of losing nerves and strength to tackle the emerging situation of semi-starvation although State help of ration and fodder was provided to them within time, which they nonetheless found inadequate. A state of silent mental turmoil emerged in 1985, reflected in growing collective anxiety, leading to outbreak of migration.

Migrants of Kharnakling Leh have formed puzzled perceptions. Interaction reveals they have nurtured mystified view of the past and the present, leading to muddled statements. Contradictions and paradoxes are common. They find themselves in a state of indecisiveness. Forced migration has impacted their innocent psyche. Their views on life are incoherent and inconsistent. On the one hand, migrants say they faced difficulties, on the other hand they deny importance to those difficulties. On the one hand, they say old culture, river, area, mountain, snow, grasses were good and they felt captivated by aesthetics of nature; they recall everything of past life to return. On the other hand, they say it was difficult living there. On the one hand, they say “everyone in tribe should get grass and ration; we requested government to provide adequate grass, provisions for full four months; 20 quintals of grass was inadequate for 500 goats for four months; feed and ration too was inadequate”. On the other hand they display sensitive understanding of real situation: “Government cannot provide assistance in-kind to everyone; it may be able to extend help at the most to one or two villages”. Soon they take recourse to self-interest, individualism and self-indulgence: “If government says nomads should re-distribute assistance equally among themselves, how is that possible?” Mystification of reality muddled with individualized narrow self-interest and overt socialized altruism may not facilitate understanding of real reasons of migration.

Population of nomad households increased and it put pressure on natural resources, particularly after the settlement of over 3000 Tibetan refugees in Changthang. If a cluster of Rabo nomads had 10 households 100 years ago, their number increased to 80 households 30 years back. It shows eight times or 700% growth in 70 years i.e., 10% per year. Even if it is considered that family size became half, it means 5% annual growth in population, which is very high. This high growth in population of nomads may not have been possible without support of nature that provides nourishment. If nature had not produced adequate grasses, bushes and wheat to support life, this much growth in population of nomads would have been impossible. However, there is limit to growth. Growth in population could not be sustained after mid-1980s. Migration process of nomads continued for a decade, up to 1995.

Triggering factor of mass migration is high population growth of nomads. The same environment and natural conditions which allowed population to grow also at some time (1985) forced “excess” number of nomads to abandon that area to make exodus. Migration could also be linked with “climate change” while actual beginning of change in climate in context of Rabo nomads may have been made even before 1985. Tribal nomadic hilly terrain of Changthang, devoid of grass-cover/ vegetation experienced calamitous and catastrophic conditions with seven feet snowfall, without adequate supply of feed, fodder and food from outside. Large number of livestock (Pashmina goats, sheep, horses) had died. Nomads, feeling surely not the fittest to adapt and survive, migrated early on before perishing in cold. It was their quick response to the situation. Climate change probably triggered mass exodus even as heavy snowfall made physical survival impossible amid semi-starvation conditions. A combined trigger of climate change and population growth had set-in before 1985. Migration was just a few ticks away in 1985.

State assistance could not ensure adequate succor and survivability by food ration, grass, medical help, veterinary aid, etc. Force of nature turned hostile for a while, and authoritative force was insufficient to turn tide in their favor by way of government help. Nomads kept migrating over the decade of 1985 to 1995 until 150-200 nomadic households left their original abode. Other accelerating factors behind mass migration are: attraction of wage-labor; lure of Leh city; glow of capital; lure of permanent settlement; lure of assistance at Leh; attraction of post-nomadic capitalistic way of life & culture based on money income though not inclined to savings-accumulation. They were set to acquire this new culture. Pressure on land-grass-vegetation-water resources influenced the life and survivability of Rabo nomads. By 1985 it attained unbearable proportions. Role of settlement of 3000 Tibetan refugees in Changthang in Rabos’ migration may not be ruled out.

Migrants are still in transition 30 years after migration as they find hard to get fully assimilated with new mode of settled life. It would take some more time to judge whether migrants really succeeded in coping with difficulties at Leh. They are yet to decide whether to go back to their roots in Kharnakzara-Nyoma tribal mutual help clusters, to lead nomadic way of life in Yak-Pashmina woolen tents, or should they get settled in permanent ‘kutcha’ houses by forming Self-Help Groups at Leh. For present they are content with wage-labor for economic survival as “one-dimensional” economic beings dragged away from lap of Nature which nurtured them as natural beings.

(Author works for NABARD. Views expressed are personal)

Feedback:mohinder1966@gmail.com