LONDON: Scientists have successfully created artifical mouse embryos in lab, using a 3D scaffold and the body’s master stem cells, an advance that may explain why more than two out of three human pregnancies fail.

Once a mammalian egg has been fertilised by a sperm, it divides multiple times to generate a small, free-floating ball of stem cells.

The particular stem cells that will eventually make the future body, the embryonic stem cells (ESCs) cluster together inside the embryo towards one end: this stage of development is known as the blastocyst.

The other two types of stem cell in the blastocyst are the extra-embryonic trophoblast stem cells (TSCs), which will form the placenta; and primitive endoderm stem cells that will form the so-called yolk sac, ensuring that the foetus’s organs develop properly and providing essential nutrients.

Previous attempts to grow embryo-like structures using only ESCs have had limited success. This is because early embryo development requires the different types of cell to coordinate closely with each other.

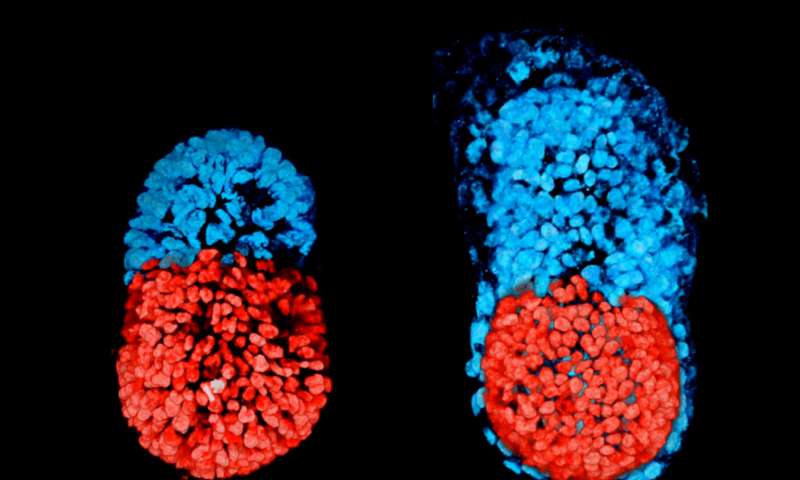

Researchers from the University of Cambridge in the UK used a combination of genetically-modified mouse ESCs and TSCs, together with a 3D scaffold known as an extracellular matrix, they were able to grow a structure capable of assembling itself and whose development and architecture very closely resembled the natural embryo.

“Both the embryonic and extra-embryonic cells start to talk to each other and become organised into a structure that looks like and behaves like an embryo,” said Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz from Cambridge, who led the research.

“It has anatomically correct regions that develop in the right place and at the right time,” said Zernicka-Goetz.

Researchers found a remarkable degree of communication between the two types of stem cell: in a sense, the cells are telling each other where in the embryo to place themselves.

“We knew that interactions between the different types of stem cell are important for development, but the striking thing that our new work illustrates is that this is a real partnership – these cells truly guide each other,” she said.

“Without this partnership, the correct development of shape and form and the timely activity of key biological mechanisms doesn’t take place properly,” she added.

Comparing the artificial ’embryo’ to a normally-developing embryo, the team was able to show that its development followed the same pattern of development.

The stem cells organise themselves, with ESCs at one end and TSCs at the other. A cavity opens then up within each cluster before joining together, eventually to become the large, pro-amniotic cavity in which the embryo will develop.

The study was published in the journal Science. (AGENCIES)

Trending Now

E-Paper