Dr R L Bhat

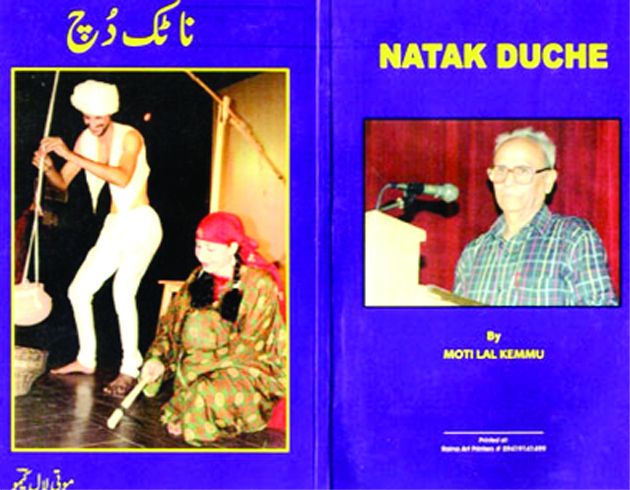

Yet again, the thespian of Kashmir, Moti Lal Kemmu in his latest offering Natak Duche, has employed the traditional art form of Kashmir, paa’thu’r to focus attention on some very contemporary issues – the increasing encroachment of human habitations on agricultural land and the black money stashed away in Swiss banks. The issues are as well known as they are elusive. Public, government, departments all are seized of the fact that the increasing use of agriculture and forest land to build colonies is devastating the environment. All concede the need for turning back this tide. Yet all the three, the people the concerned departments and the government are actively pushing this very flood that they see as bad in principle and are committed to stop. Aaru’mu’ny Paa’thu’r the first of the two naattaks in Natak Duche deals with this burning issue. And, the master craftsman, Kemmu, does it in his characteristically innovative yet simple way.

Aaru’mu’ny Paa’thu’r is one of the paa’thu’rs or folk theatre ways prevalent among the baandds of Kashmir. Deriving their name from the Sanskrit bhaanddam – buffoonery – baandds have been the traditional entertainers of the valley. There are well known villages of these folk artists in three regions of the valley, Anantnag, Srinagar and Baarahmulah. Kemmu’s contribution in reviving this traditional community of artists of Kashmir has been well documented by now, as he has been involved in it for the last half a century. As the first cultural officer of JKAACL, Kemmu traversed the length and breadth of the valley and reached out to the few baandd villages, then, on the verge of extinction. His efforts bore fruit and paa’thu’r began to thrive, anew. Baandds were activated, Paa’thu’r got revived. In the decades following it became a cultural mainstay and the community prospered.

Then came the turmoil – militancy, terrorism, whatever you may like to call it. Like all people with an independent and liberal outlook, the baandds too suffered persecution at the hands of fundamentalists. Paa’thu’r shrank as prohibitive dictates were issued out to baandds. By mid-1990’s paa’thu’r had shriveled to the state it was in 1950’s, when Moti Lal Kemmu had set out to rejuvenate it. He did it again. Not ready to see his work of a life-time drying up, he went from Jammu at grave risk of limb and life and activised the folk artists. He wrote for them, taught the baandd youngsters their ways and modes of art. He did direction work and by the turn of the century had the traditional Kashmiri theatre back on the state and national scene. His ‘Dakh Yeli tsalan’ was a reiteration of the urge of baandds to keep doing theatre even as it meant a threat to the very life. The drama was so huge a success that it was translated into many languages and performed on Non-Kashmiri stages. Over the last two decades, Kemmu has been the most active theatre personality of Kashmir. He is also the most acclaimed one.

Paa’thu’r – threaticals – is generic term for the folk theatre of Kashmir. The artists i.e. baandds had general drama outlines called Paa’thu’r which they played. Depending upon the particular subject these came to be known as Shah paa’thu’r, juugy paa’thu’r, etc. These names delineated the general theme and characters, costumes, styles and evocations both verbal and gestural. Within the general outline, the artists improvised all deportments to bring in new elements, tackle issues of the day and make novel presentations. Aaru’mu’ny paa’thu’r is one general outline, focused on the vegetable growers of Kashmir called aaru’my. Kemmu contests the view expressed by some that it does not represent a distinct outline or paa’thu’r theme. There have been communities in Kashmir engaged specific jobs, like growing vegetables here, who over long period of time developed distinct way of living, speaking, dressing and general behavior. Paa’thu’r worked on these distinctions and made presentation which focused on their visible characteristics. The paa’thu’r that takes the community as the particular focus becomes aaru’mu’ny paa’thu’r. Built around their needs and problems and highlighting their peculiarities to evolve humorous lines and situations, the specific paa’thu’r fulfilled their own artistic needs of expression and entertained the public. As Kemmu’s Aaru’mu’ny Paa’thu’r shows the group has a full repertoire of special attributes to sustain a paa’thu’r.

Aaru’mu’ny paa’thu’r may not have been as common a theme outline as say Shah paa’thu’r or juugy paa’thu’r. These had a wider appeal as attributes could be understood by the general audience. People at large could understand the words and attitudes of the kings and yoogiis depicted even caricatured in the paa’thu’r and enjoy them. Kemmu’s paa’thu’r in Natak Duche, has the rich vocabulary of aaru’my community, which can be fully understood only by people living around the communities of these traditional vegetable growers of Kashmir. Paa’thu’r builds on the nuances of usages of the focal group. Emphathy upon which dramatics live is evoked on comprehension of these. This author too only just made out the meaning of tool paazun and many other specific used by Kemmu. They would hinder one to emphathise fully with the implied evocations. These things would have limited the reach of aru’mu’ny paa’th’ur. But they also tell that the specifics were enough and distinct to support this paa’thu’r.

Kemmu uses all of this specific arsenal in his paa’thu’r, to tell that progress or development has had fatal implications for the special call of aaru’mu’ny community. The general corruption visits the community in the shape of the pent-shirt clad VLW, who would not release water unless bribed. They would’ve come to terms with this disease and probably did as the head of the community threatened a public agitation if he pestered them again. They, however, could do nothing about the approaching menace of colonization. Colonizers bought their land for building and finished off the aaru’my village. On the other end the forests too, are being decimated, for the same purpose. A special community, a special trade, a resource and a living… all get effaced in the advance of this progress. Kemmu tells it, proving that aaru’mu’ny paa’thu’r was a robust theme, though its survival would not be guaranteed.

The second creation in Natak Duche is a one-act play Jaa’dygar – The Magician. The play to be performed on a single stage setting is told as a daastaan – tale – with a daastaangoo (teller of tales) presenting it. This is the traditional suutradhaar of Indian drama. He tells the tale of a kingdom, of a worthless king named Sakhaavat Shah (king of generosity) whom the people have given the apt nickname nyam nyam shah (king sans a spine). A menace stalks the land, forcing the people to raise a hue and cry but the Shah is gorging on sweet dishes and then sleeping them out. The people finding no succor resort to that ultimate instrument of public, the agitation. It brings out the king. When finally forced to attend to the outcry, he has no solution. His minister, equally worthless, shows total helplessness.

The administration, police and army all fail to control the thing menacing the land. Then comes a magician who claims that he can control it. They fall for a magician. After gaining their confidence with verbal, magical and aerobatic acts, he has the king, the minister and the people under his spell. He offers to present a novel trick during the course of which he loots the treasures and decamps. Shah calls for army, helicopters et. el. to find him but he has fled away. Giving the whole tale a contemporary twang, the suutradhaar tells that he has deposited his loot in Swiss banks in his own his wife’s name and none can do anything. From the pen of the master of the art, the naattaka, Jaa’dygar is an incisive comment on the issue of black money in foreign banks. The innovative manner of portraying intricate acts on stage has allowed the dramatist to bring elements of film portraiture into a stage play.

Over the past years besides his yeomanry among the folk artists of Kashmir, M L Kemmu has been holding workshops at Jammu to train youngsters. Training young uninitiated boys and girls drawn from the exiled Kashmiris and local Jammuvities, Kemmu has presented half a dozen Kashmiri dramas and paa’thu’rs at Jammu during the past decade. His efforts to attract new talent to this old art form is a laudable contribution of this thespian of the state. His versatile genius of writing directing and training raw youth in the demanding art of drama, is a great contribution to the cultural enrichment of the state. This latest work of M L Kemmu, Natak Duche, is an equally great contribution to the literature of the state.