Suman Gupta

An article on Andrew Wyeth in the Time magazine in the year 1986, related to the series of works done by him secretly with his German model, was the first time I ever saw his work. Looking at his work for the first time was like love at the first sight. After this first encounter, I became a true believer in his work and I still hold this opinion, although I’m aware that many others don’t share it.

His work has had a profound impact on my carrier as an artist. Soon after this, I sent a handwritten letter to the master expressing my deep appreciation for his art and the impact it’d had on me. To my surprise, one of America’s best known twentieth-century artists, replied soon with his handwritten letter, which has become an important part of my archives. There was a great desire to meet him in person but he died in his sleep in the year 2009 after producing a series of some of the finest works in the nine decades of his career as a famous American artist. My dream to meet him in person too died with him.

It was during my ‘One Man Show’ at the Gallery Christine Frechard in Pittsburgh, U.S.A. that I finally decided to visit the place where he had been living and painting for the last many decades of his life and get a feel of the place and its people. It was more important for me to see his studio and see his works physically than anything else during my trip, because very few contemporary artists in the world have mastered the technique of egg tempera like him with such precision, commitment, discipline and devotion.

My ‘One Man Show’ “Hopes and Dreams” opened on September 3, 2014 and was to remain open to public till October 7. The opening was a wonderful experience both for me and my wife Joy, who was also accompanying me during the show. Soon after the opening, we planned a trip to New York where we spent around ten days and saw the famous ‘Christina’s World’, one of the most popular and important works produced by Wyeth at MOMA. The Museum had acquired this work from the artist soon after its completion. I also had to see some major museums and galleries in NY since it was my very first visit to the US. Yet, I must say that looking at ‘Christina’s World’, which is one of the most durable and disquieting images of the 20th century America, was a profound experience. Against the wall of landscape that leads up to her house, the painting depicts the crippled body of an ageless woman who seems trapped, imprisoned by the very emptiness of the earth. Its meticulous execution was just so wonderful that I almost spend more than one hour only to observe and study the technicalities of the execution part of the painting.

THE MUSEUM

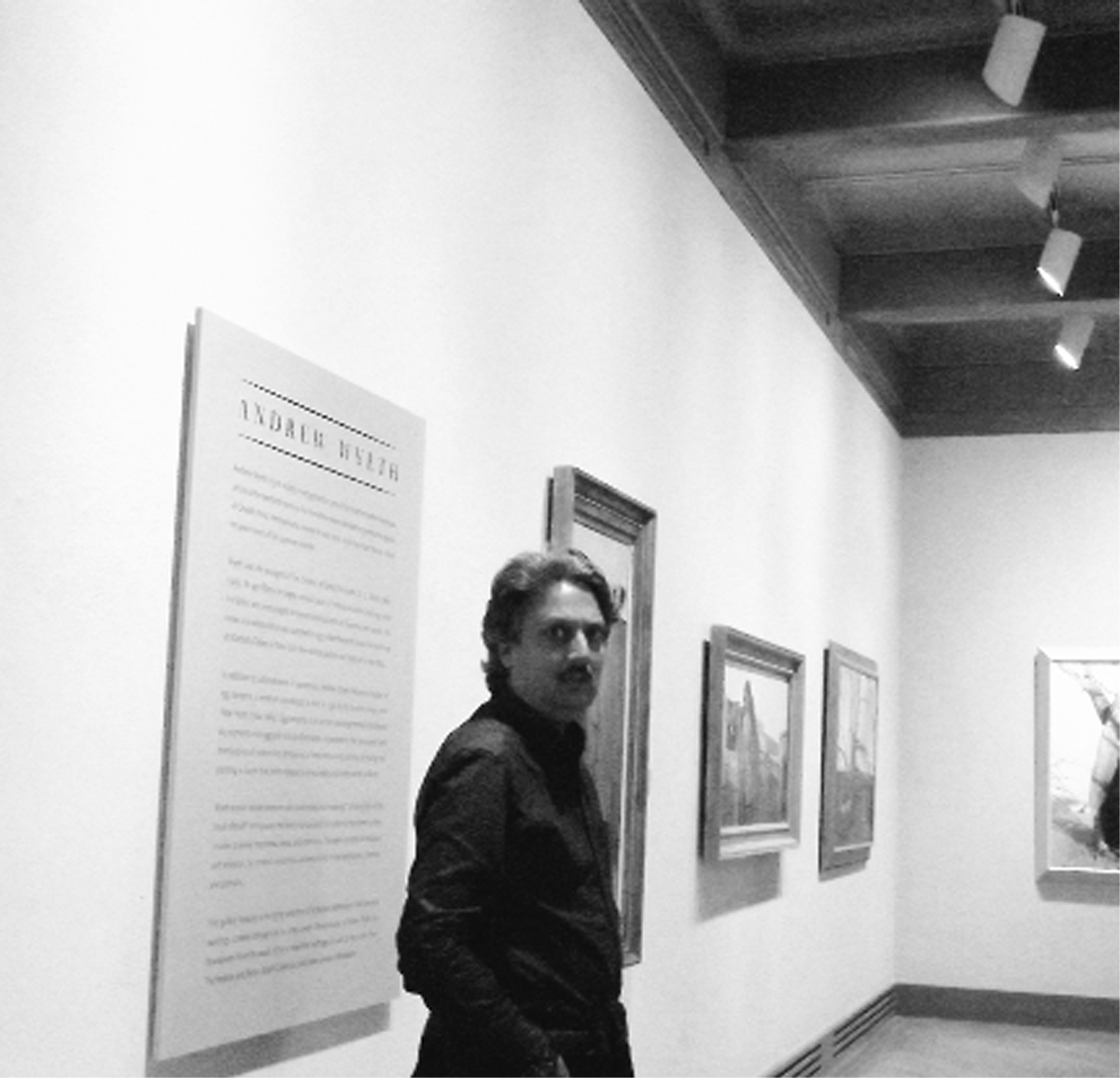

After coming back to Pittsburgh to attend my talk organized by the Gallery, we went back to Philadelphia and from there we caught the bus to Chadds Ford in Wilmington. The journey from Philadelphia to Chadds Ford was not as easy as we had thought but somehow we did manage to reach up to our hotel which we had already booked while travelling from India. Next day it was our first visit to the Brandywine River Museum and Andrew Wyeth Studio in Chadds Ford. I was very excited to see everything. We took a morning taxi which took us some 45 minutes to reach our destination. Finally we saw the Museum signboard on the highway and made our way inside the inner lane and caught the very first glimpse of the Museum. The Brandywine River Museum is a museum of regional and American art located on U.S. Route 1 in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania on the banks of the Brandywine Creek. The Museum showcases the art of Andrew Wyeth and his family including his father N.C. Wyeth. After buying our tickets, which covered both the Museum as well as the Studio where Andrew Wyeth had worked, we entered a very simple and old looking building with a feel of Wyeth paintings. I was curious to see the work of Andrew Wyeth more closely than the works of other family members. So, after looking at the work of N.C.Wyeth, Johan McCoy and Peter Hurd, I finally entered the Andrew Wyeth Gallery and lo and behold, here it was, ‘The Night Sleeper’, ‘Roasted Chestnuts’, ‘Dryad ‘ and few works from his Helga series right before my eyes. For nearly 60 years Andrew Wyeth spent every fall and winter in Chadds Ford. Wyeth was an astute observer who once noted that meaning “is hiding behind the mask of truth” in his work. He freely manipulated his subjects, transforming them in order to evoke memories, ideas, and emotions. Through a process of reduction and selection, he created mysterious undercurrents in his landscapes, interiors, and portraits.

After coming back to Pittsburgh to attend my talk organized by the Gallery, we went back to Philadelphia and from there we caught the bus to Chadds Ford in Wilmington. The journey from Philadelphia to Chadds Ford was not as easy as we had thought but somehow we did manage to reach up to our hotel which we had already booked while travelling from India. Next day it was our first visit to the Brandywine River Museum and Andrew Wyeth Studio in Chadds Ford. I was very excited to see everything. We took a morning taxi which took us some 45 minutes to reach our destination. Finally we saw the Museum signboard on the highway and made our way inside the inner lane and caught the very first glimpse of the Museum. The Brandywine River Museum is a museum of regional and American art located on U.S. Route 1 in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania on the banks of the Brandywine Creek. The Museum showcases the art of Andrew Wyeth and his family including his father N.C. Wyeth. After buying our tickets, which covered both the Museum as well as the Studio where Andrew Wyeth had worked, we entered a very simple and old looking building with a feel of Wyeth paintings. I was curious to see the work of Andrew Wyeth more closely than the works of other family members. So, after looking at the work of N.C.Wyeth, Johan McCoy and Peter Hurd, I finally entered the Andrew Wyeth Gallery and lo and behold, here it was, ‘The Night Sleeper’, ‘Roasted Chestnuts’, ‘Dryad ‘ and few works from his Helga series right before my eyes. For nearly 60 years Andrew Wyeth spent every fall and winter in Chadds Ford. Wyeth was an astute observer who once noted that meaning “is hiding behind the mask of truth” in his work. He freely manipulated his subjects, transforming them in order to evoke memories, ideas, and emotions. Through a process of reduction and selection, he created mysterious undercurrents in his landscapes, interiors, and portraits.

THE STUDIO

When it came to his work, Wyeth was very private – a proclivity that is underscored by a sign tacked to the front door: “I do not sign autographs.” Even with his family, he could be secretive. He rarely told anyone, including his wife, where he was going when he left his house in the morning to paint. His palette was the countryside along the Brandywine: the sky, the grass, the animals, the houses and the people that he had known since childhood.

Soon after visiting the Brandywine Museum we had our lunch at the Museum restaurant and the Museum car took us to Wyeth studio. Andrew Wyeth painted many of his most important works of art in his Chadds Ford Studio.

“I feel limited if I travel”, he once told Thomas Hoving, then the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “I feel freer in surroundings that I don’t have to be conscious of. I’ll say that I love the object, or I love the hill. But that hill sets me free. I could wander over countless hills. But this one hill becomes thousands of hills to me.” Wyeth discovered Karl and Anna Kuerner’s farm on one of his boyhood walks. Migrants, who settled in Chadds Ford after World War I, fascinated the artist. Over time, he developed a complex relationship with Kuerner’s German family and painted some of his best-known works of art in the backdrop of this bonding. Chadds Ford, which is smaller than nine square miles, provided the inspiration and privacy Wyeth needed. Most of his life he worked seven days a week, leaving his home at 8:30 a.m. and returning at 5:30 p.m. From the 1940s to the 1960s, Andrew Wyeth achieved acclaim seldom, if ever, given to an American artist. On three occasions, major American museums acquired paintings he had made, with each purchase setting a new record for a living artist. In 1963, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Eight years later, Life magazine anointed him “America’s preeminent painter.”The great connoisseur of Italian art, Bernard Berenson, wrote admirably about Wyeth’s work in his diary. The poet Robert Frost was an enthusiastic fan. The statesmen Winston Churchill, when he visited Boston, made arrangements to have Wyeth watercolors hang in his hotel room at the Ritz.

Andrew Wyeth sought – and achieved – independence his whole life. But he was also strongly connected both to the landscapes and people where he lived. In spite of the reticence of his national artistic profile, Wyeth loved to look at and into people in the same way he dissected landscapes. My own view is that he fits into a larger tradition of modernist creativity that goes beyond the medium of painting, one that’s also found in novels and movies – a tradition of attending to the overlooked. His influence – like that of his contemporary Edward Hopper – has been most important and profound not only in the realm of painting, but also in poetry, literature and filmmaking.

Trending Now

E-Paper