Bollywood songs with jewels and ornaments used in the lyrics have enriched the melody and the rhythm of the films. Shoma A. Chatterji probes into the Hindi film song with women’s jewellery as the subject and explores its significance.

Gunga Jumna (1961) was one of the biggest box office hits of the year. It was produced by Dilip Kumar who portrayed the dual role of twin brothers and directed by Nitin Bose who migrated from New Theatres to Mumbai in the 1940s. One song that remains immortalised is dhundo dhundo re saajana more kaan ka bala sung and danced by Vyjayanthimala . The lyrics were by Shakeel Badayuni and the music was by Naushad, both milestone creators in their respective fields.

The song was picturised on Dilip Kumar and Vyjayanthimala in a playful scene of love and teasing following their nuptial night. Dhanno (Vyjayantimala) suddenly discovers that one of her danglers is missing. She takes off the other one, dangles it and begins to dance. A little later, we discover the missing earring stuck to Dilip Kumar’s kurta, but the two are oblivious. It carries a sensual and erotic suggestion on the nuptial night with the bed strewn with dried up flowers. Both Dilip Kumar and Vyjayantimala won the Best Actor Awards from Filmfare for their work in the film.

Jhumka Gira Re from Mera Saaya (1966) with lyrics penned by Raja Mehdi Ali Khan and sung by Asha Bhosle to music composed by Madan Mohan is lip-synched by a gypsy girl performing to an audience on the streets of a city (Bareilly?) to a male crowd. Her costume and jewellery, designed by Bhanu Athaiya, fit into the scheme of a gypsy performer with double-entendre lyrics that could mean several things – literal, metaphorical and suggestive. This reverses the kaan ka bala metaphor to now shift to a public performer away from the mainstream. The use of the word ‘bajaar’ in the second line, meaning ‘market’ makes the connection obvious.

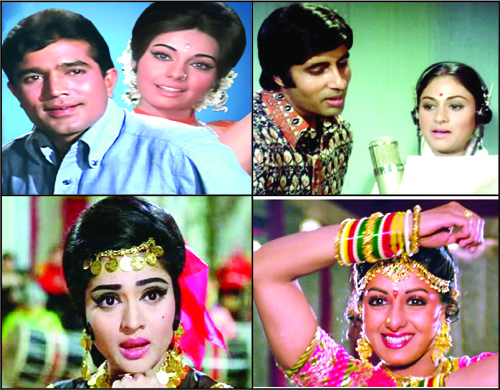

Bindiya chamkegi, chudi khankegi from Do Raaste (1969) is a romantic song picturised on the hit pair Mumtaz and Rajesh Khanna under the directorial baton of Raj Khosla whose sense of music, songs and their picturisation remain carved in cinema history. The picturisation of the song composed by Lakshmikant-Pyarelal on lyrics penned by Anand Bakshi and sung by Lata Mangeshkar throws up a model lesson on how song-dance numbers should be ideally picturised. Mumtaz wore a bright orange sari with lots of flowers in her hair and was decked generously in silver jewellery.

She tried to divert the attention of the hero studying on the terrace and managed to seduce the camera with her underplayed sensuality. At one point, the hero bites an ear-ring she is wearing but she seems not to pay attention. The camera has experimented with innovative angles to shoot the lady in close-up, in mid-shots, through the hole where the rest of the screen is black and so on. The lyrics are rich with meaning. At once place, she sings – maine muhabbat kee hai, ghulami nahi kee maine which is eloquent in its feminist stance within a very patriarchal backdrop. The song thus reaches far beyond the ornaments and make-up such as payaliya, kanganaand kajara used in the same song. The musical interludes filled with brilliant beats compliment the lyrics without dominating them.

Teri Bindiya Re from Abhimaan (1973) has survived the onslaughts of time, globalization and post-modern cinema. It is a love song picturised on Amitabh and Jaya Bachchan in the film after they have just married. The lyrics by Gulzar use the words “bindiya”, “nindiya” “gehna”, “kangana” and “angana” apparently as a rhyming strategy but listened to closely, it enlarges the horizons of the literal and ritualistic significance of the ornaments to embrace a life-view of togetherness and love.

The bride says that while her ‘bindiya” will steal his ‘nindiya’(sleep), she considers him her ‘gehna” – composite jewellery and rejoices in the thought of being part of his angana (metaphorical compound of the home they will make together). Enriched with the beautiful music of S.D. Burman with the magic voices of Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammed Rafi, this song is an ideal example of how cinema can and has used jewellery – an everyday marker of womanhood to mean much more than what it means in real life.

Sreedevi dances to the song number mere haathon mein nau nau chooriyan hai in Chandni (1989) to lyrics by Anand Bakshi and music by the Shiv-Hari duo at a sangeet ceremony for a cousin’s marriage where men are not allowed. Wearing a pink ghaghra-choli-odhni filled with zardozi and decked in heavy jewellery, she places the focus on the colourful bangles in her hand which, unlike the rest of the gold she wears, includes cheaper bangles of plastic, This is purely an ingredient for entertainment with a dance number by Sreedevi put in to raise the box office value of the film. There is a romantic teaser in that the hero (Rishi Kapoor) tries to smuggle himself in by covering his head with a towel and pleads with other women when caught to let him stay just to ogle at the girl he is falling in love with.

These song numbers and many more provide a cultural map to our past because much of this jewellery has changed in significance and in use and has broadened to include an increased consumer base across the world.

Rings of different kinds are now inserted in the belly button, on the chin, and tattoos are used in place of jewellery by girls, and often boys, in a global world where culture-specific and gender-centric connotations that jewellery once held are slowly but steadily fading away. Historically however, they will continue to enrich the history of cinema and its socio-cultural significance now and in the future. TWF