BOSTON: Researchers have carried out what they claim to be the coldest chemical reaction in the known universe — at a temperature millions of times colder than interstellar space — an advance that may lead to more efficient energy production.

The study, published in the journal Science, described the moment when two molecules meet to form two new molecules, which the researchers said captures a chemical reaction in its most critical and elusive act.

The researchers, including Kang-Kuen Ni from Harvard University in the US, said at such intense cold — 500 nanokelvin, or just a few millionths of a degree above the lowest possible temperature in the universe — their reacting molecules slowed to glacial speeds.

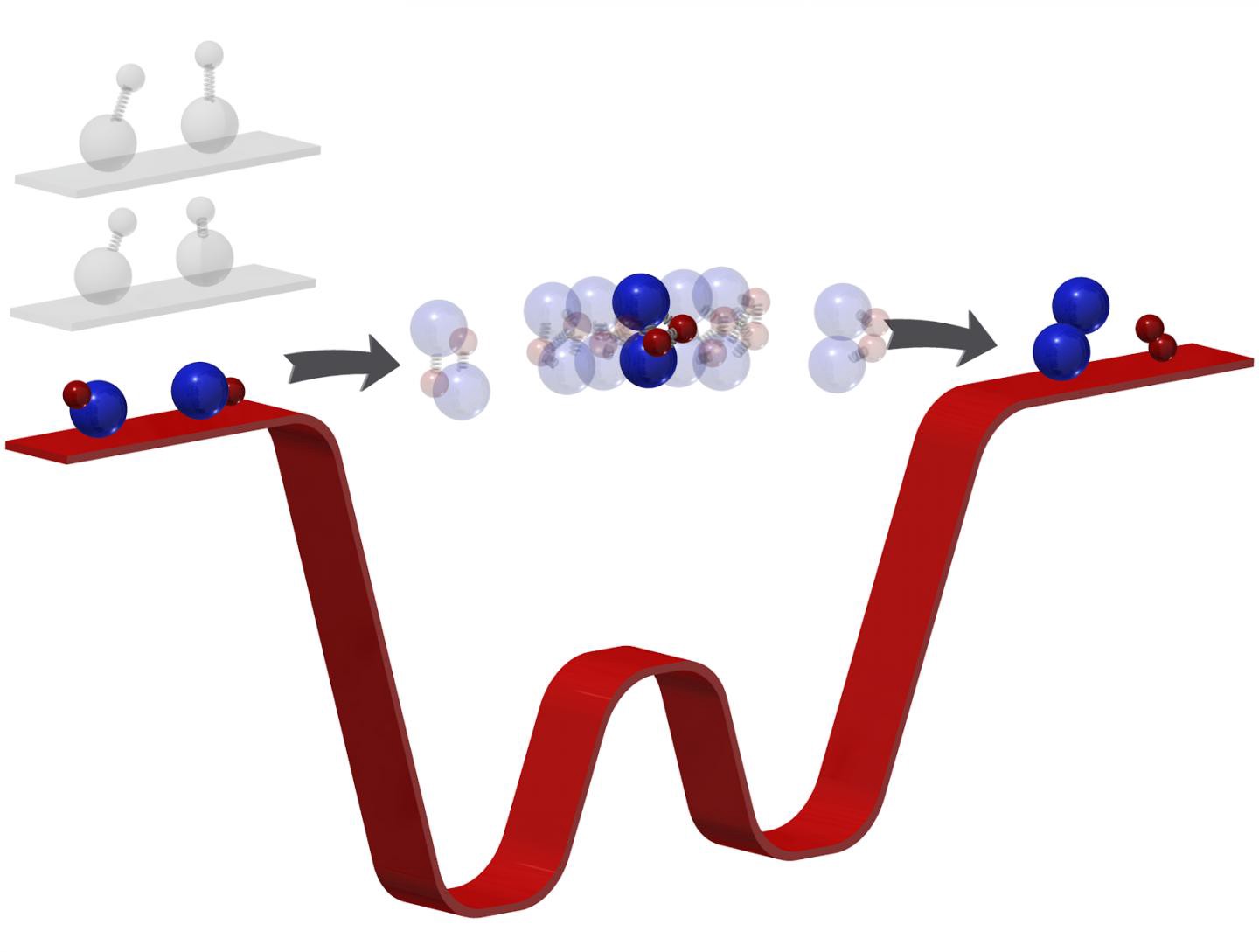

When two molecules containing two atoms each collide, they sometimes swap partners, they said.

“For instance, two potassium-rubidium (KRb) molecules can produce K2 and Rb2. The four-atom intermediate formed upon collision is typically too scarce and short-lived to spot, even using ultrafast techniques,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Ni used ultra cold temperatures in her earlier research to forge molecules from atoms that never reacted otherwise.

At such extreme temperatures, she said, atoms and molecules slow to their lowest possible energy state, allowing scientists to manipulate their interactions with utmost precision.

However, the researchers said they could never see what happened at the very beginning of these ultracold reactions.

They said chemical reactions occurred in just millionths of a billionth of a second — in what are called femtoseconds.

According to the researchers, even today’s most sophisticated technology can’t capture something so short-lived.

They said scientists have been using ultrafast lasers to snap rapid images of reactions as they occur like fast-action cameras.

However, even these setups can’t capture the whole picture, the researchers said.

“Most of the time, you just see that the reactants disappear and the products appear in a time that you can measure. There was no direct measurement of what actually happened in these chemical reactions,” Ni said.

In the current study, the ultracold temperatures forced reactions to a comparatively numbed speed, the researchers said.

“Because [the molecules] are so cold, now we kind of have a bottleneck effect,” Ni said.

When Ni and her team reacted two potassium rubidium molecules, the ultracold temperatures forced the two molecules to linger in the intermediate stage for millionths of a second.

These microsecond time scales, while not too short, the researchers said, were millions of times longer than usual, and long enough for them to investigate the phase when bonds break and form, which is essentially how one molecule turns into another.

The researchers plan to observe reactions at this time scale, and test theories that predict how bonds form.

Using the observations, the scientists plan to craft new theories, using actual data to more precisely predict what happens during chemical reactions, they said. (agencies)

Trending Now

E-Paper