B L Razdan

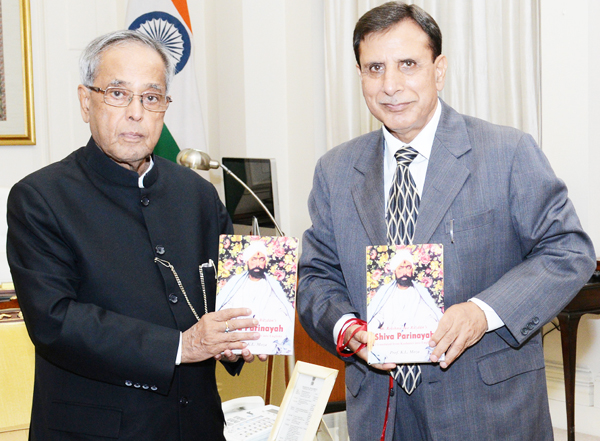

Professor Kanhaiya Lal Moza has passed away and my heart is bleeding in deep anguish and pain. This feeling is all the more accentuated by the tragic irony that while I was having the book “Shiv Parinayah” authoured by him released by the Honourable President of India at Rashtrapati Bhawan in New Delhi on 25th July, 2013, Professor Moza was breathing his last at Jammu. While his enlightening book was exchanging hands in New Delhi, the light that produced it was extinguishing at Jammu. The most popular teacher and the self-effacing crusader, who was loved even by the militants in Srinagar and was even protected by them even during the peak of militancy, left Srinagar only to marry his children and when his health started failing him, found Jammu convenient to stay.

When I had asked him how should he be introduced to the prospective readers of the book – his pet project – this is how he wanted himself to be described, “Born in 1939; his critical evaluations of Kashmiri literary works published in numerous journals and magazines; several translations of Kashmiri prose and poetry published by Sahitya Academi; retired as a professor of English from Gandhi Memorial College, Raipur, Jammu; taught English to undergraduate and post-graduate classes in the Srinagar campus of Gandhi Memorial College; presently engaged in critical appraisal of Kashmniri Hindu literary luminaries.” He did not permit me even an additional word of praise or opinion even though I had insisted upon. Probably because of his simple nature revealed by what is unsaid in this brief introduction I held him in the highest esteem and had nothing but reverential regards for him. My visits to Jammu were incomplete without calling upon him at his residence.

A couple of years back when his son Yudhishtger was travelling from Lucknow to Delhi alongwith his family, the car met with a serious accident in which his son was badly hurt and his less than one and a half year old grand daughter, Sampada, died. He wanted the book to be dedicated to her memory and wrote below her photograph, “Baby Sampada Moza (22.01.2007 – 06.06.2009) fondly remembered by Dadi and Dada, Smt. Mohini Dhar Moza and Shri K. L. Moza. Today when the intorductory page of the book is adorned with this dedication, he is not there to see it.

It took quite a while for Yudhisther to recover from the critical injuries he had received in the accident. Professor Moza himself sufferred from the most painful of the diseases and had to undergo several sessions of chemotherapy; but I always found him a picture of calm and fortitude, always immersed in the work he had undertaked to retrieve the lost heritage of the Kashmiri Pandiats. Tragically again, I had emailed him the semi-corrected manuscript of another book titled “Kashmiri Hindu Literature – An Anthology of Critical Essays & Translations”, the job of publishing which he had entrusted to me, just a week ago, for his suggestions on arrangement of chapters, etc. Now, I may have to do it myself; the masters’s magic touch will be missing. And what was his magic touch? Please read the foreword to his book just released, which reads as under:

“Translators have always trembled in their attempts to translate from one language into another. This has been more starkly true when the subject matter of the transaction is poetry. The reasons are not far to seek. “The beauties of poetry cannot be preserved”, said Samuel Johnson, “in any language except that in which it was originally written.” This remark is true about kashmiri poetry as well and truer of Krishnajoo Razdan’s poetry for the simple reason that the poetic formats and idioms of expression devised by him served as models for his contemporaries and followers alike, which, in a way, justifies the validity of the erudite critical opinion that Krishnajoo Razdan is a poets’ poet. Instead of hurrying through narrative segments of his lyrics, to quote Prof. Moza, we observe him luxuriating in deliberate verbal stokes for conjuring up some captivating aspects of the nineteenth century kashmiri Hindus life. Evidently, it is not easy to translate the rhyming couplets and musical quatrains, the narration of which is ingratiating in the tracts where the poet adopts rhyming couplets embellished with sweet metaphors, similes, alliterations and assonances. In the circumstances, one shudders to imagine the arduousness of the task of translating his Kashmiri poems into English poetry while preserving the inimitable charm infused by the author by the clever use of Arabic, Persian, and Indian elements of the poetical language, each of which bears not only its simple meaning but also different accessory notions. That Professor K. L. Moza, who has several translations to his credit, was able to do precisely do the same with comparative ease only speaks volumes not only about his mastery over English language, of which he is an acknowledged authority in his own right, but also of his profound scholarship of our sacred scriptures, erudition, and the fertile imagination that so activated the genius in him as to enable him to grasp the spirit of each Kashmir poem, nay, of each couplet of Krishanjoo Razdan’s poetry into beautifully varnished and taut English couplets aimed primarily at introducing the Kashmiri poet to the English world to make them realise that the genius of Razdan was no less than that of their own poets; but because of the limited reach of the Kashmiri language, he did not get the recognition that he so richly deserved. During his time the poetry, especially Indian poetry, was a prisoner of philosophical thought as was the case with most of his contemporary poets. To Krishnajoo Razdan, however, goes the credit of disentangling poetry from philosophy through his mature artistic efforts. As observed by Prof Moza of Razdan’s poetic compositions transparently objectify his deep conviction that the principal concern of literature should be to portray and not to preach. That also makes him a people’s poet as well in that the language and the imagination used by him is comparatively easily comprenesible Words fail us in expressing our gratitude to Prof. Moza for this invaluable favour. We can do no better than to offer him our reverential regards and pray for his long and healthy life to enable him to realize the stupendous goal he has set before himself ‘Amen!”

Unfortunately, our prayers have been only half answered. The doyen of our cultural ethos has orphaned us when we need him the most. In mourning his loss we could do no better than work for the ideals he cherished and continue the crusade launched by him.