Bilal Gani

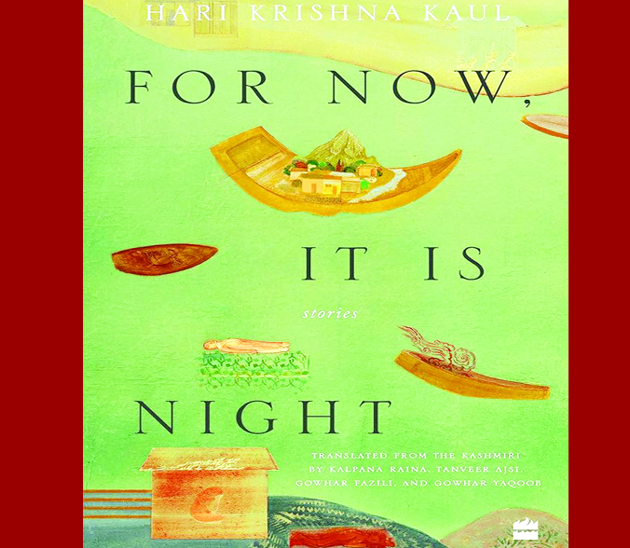

For Now, It Is Night: Stories, Hari Krishna Kaul, translated from the Kashmiri by Kalpana Raina, Tanveer Ajsi, Gowhar Fazili, Gowhar Yaqoob, Harper Collins India, 2023

In the somber pages of history, the Pandit exodus from the Kashmir Valley unfolds as more than a mere migration; it is a tale etched in the human spirit. As homes were left behind, each brick echoing with memories, families embarked on a journey not just across geographical borders but through the labyrinth of loss and resilience. The exodus, painted with the hues of personal narratives, becomes a story of tearful goodbyes to familiar landscapes, the scent of saffron fields, and the echoes of a culture deeply rooted in the valley’s soil. It’s a narrative woven with the threads of human connection, the laughter of children now scattered, and the warmth of shared traditions severed.

Unraveling The Human Tapestry

In the poignant exploration presented in a new book For Now It is Night, Hari Krishna Kaul skillfully delves into the heart-wrenching narrative of the Pandit exodus from the Kashmir Valley. The pages come alive with the stories of a community forced to confront the profound challenge of leaving behind not just homes and landscapes, but a cultural and historical heritage deeply intertwined with the region.

The book brings together 17 short stories written between 1970 and 2000 by the prominent Kashmiri author and playwright Hari Krishna Kaul. It also contains a few previously translated stories that have appeared in various Kashmiri short stories collections edited and translated by Neerja Mattoo such as Kath: Stories from Kashmir (2011), The Greatest Kashmiri Stories Ever Told (2022), and In This Metropolis (2011) translated by Ranjana Kaul and published by Sahitya Akademi. These stories, beyond the statistics and political complexities, are a human touchstone, reminding us that even in the face of displacement, the bonds of culture and community endure. In each untold story lies the heartbeat of a people, resilient in the face of adversity, forever tethered to a home left behind, yet carried within.

In “Sunshine”, the opening short story in “For Now It is Night”, Kaul questions the Kashmiri desire to escape the harsh winter of Kashmir through his character Poshkuj, who is unable to adjust to life in Delhi during just one winter away from Kashmir. The story originally featured in the book Pat Laraan Parbat (The Mountains Will Chase) where Kaul wrote about homesickness and the attachment of Kashmiris to the valley. Published in the 1970s, this theme later became acutely painful and persistent in his and other Kashmiri writers’ and poets’ works after the 1990s.

Hari Krishna Kaul, one of the very best modern Kashmiri writers, published most of his work between 1972 and 2000. His short stories, shaped by the social crisis and political instability in Kashmir, explore – with an impressive eye for detail, biting wit, and deep empathy – themes of isolation, individual and collective alienation, corruption, and the social mores of a community that experienced a loss of homeland, culture, and language.

Through a nuanced blend of personal testimonials and a meticulous examination of historical events, Hari Krishna Kaul weaves together a narrative that encapsulates the complex emotions and experiences of the Pandit community during this tumultuous period. The author doesn’t merely recount the events; they immerse readers in the atmosphere of uncertainty, fear, and the painful decisions that shaped the destiny of a people. The book not only offers a historical account but also endeavors to capture the human aspect of the Pandit exodus. It invites readers to empathize with the individuals and families who faced unimaginable circumstances, leaving behind the familiar and venturing into an uncertain future.

The Nuanced Narratives

The book explores the rich tapestry of cultural syncretism within Kashmiri society, weaving tales of harmony and blending traditions. However, as conflict arrives, this delicate balance begins to evaporate, revealing the fragility of cultural unity in the face of external pressures. Through its narratives, the book reflects on the impact of conflict on the intricate layers of shared values and practices, shedding light on the transformative power of external forces on a once harmonious cultural landscape.

In the realm of literary endeavors, the collaborative translation of this superb collection of short stories emerges as a testament to the synergy of talented writers who, collectively, have breathed new life into the essence of the original work. Translated from Kashmiri in a silver-tongued way by Kaul’s niece and writer Kalpana Raina, Tanveer Ajsi, Gowhar Fazili and Gowhar Yaqoob, this fine translation goes beyond a rigid, formal use of the English language that creates a barrier between the way the story was intended to be told and its translated version.

Through this collaborative effort, the translators have not only conveyed the literal meaning of the text but have ventured into the realms of cultural intricacies and subtle nuances. The spirit, the emotions, and the cultural context of the original work have been meticulously preserved, allowing readers to traverse the narrative landscape as envisioned by the author.

Brilliantly translated in a unique collaborative project, For Now, It Is Night brings a comprehensive selection of Kaul’s stories to English readers for the very first time.

In the narratives surrounding the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits from the valley, it is imperative to acknowledge the nuanced history and experiences that often go unheard. While the plight of the Pandit community deserves profound attention and empathy, it is equally essential to recognize that a singular focus on their stories can inadvertently overshadow the suffering endured by the Muslim population during the same tumultuous period. The turmoil in Kashmir affected both Pandit and Muslim communities, leading to displacement, loss, and a shared sense of uncertainty. The pervasive impact of conflict has left scars on the collective memory of all Kashmiris, irrespective of religious identity. The complexity of this narrative lies in the recognition that oppression and displacement, though experienced differently, have affected diverse communities. It is crucial to foster an inclusive dialogue that encompasses the diverse narratives within Kashmir. By acknowledging the shared pain and aspirations for a peaceful resolution, we contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the region’s history and pave the way for empathy, reconciliation, and a collective vision for a harmonious future.

(The author is a researcher and writes on conflict and literary criticism.)