SINGAPORE: Microorganisms living in the gut may alter the ageing process, which could lead to the development of food-based treatment to slow it down, according to a study.

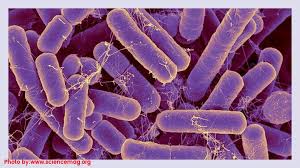

All living organisms, including humans, coexist with a myriad of microbial species living in and on them.

Research conducted over the last 20 years has established the important role gut microbes play in nutrition, physiology, metabolism and behaviour, according to a team led by Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore.

Using mice, the team led by Professor Sven Pettersson from the NTU, transplanted gut microbes from old mice (24 months old) into young, germ-free mice (six weeks old).

After eight weeks, the young mice had increased intestinal growth and production of neurons in the brain, known as neurogenesis.

The study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, showed that the increased neurogenesis was due to an enrichment of gut microbes that produce a specific short chain fatty acid, called butyrate.

Butyrate is produced through microbial fermentation of dietary fibres in the lower intestinal tract and stimulates production of a pro-longevity hormone called FGF21, which plays an important role in regulating the body’s energy and metabolism.

As we age, butyrate production is reduced, the researchers said.

They then showed that giving butyrate on its own to the young germ-free mice had the same adult neurogenesis effects.

“We’ve found that microbes collected from an old mouse have the capacity to support neural growth in a younger mouse,” said Pettersson.

“This is a surprising and very interesting observation, especially since we can mimic the neuro-stimulatory effect by using butyrate alone,” he said.

The researchers said these results will help explore whether butyrate might support repair and rebuilding in situations like stroke, spinal damage and to attenuate accelerated aging and cognitive decline.

The team also explored the effects of gut microbe transplants from old to young mice on the functions of the digestive system.

With age, the viability of small intestinal cells is reduced, and this is associated with reduced mucus production, making intestinal cells more vulnerable to damage and cell death.

However, the addition of butyrate helps to better regulate the intestinal barrier function and reduce the risk of inflammation.

The team found that mice receiving microbes from the old donor gained increases in length and width of the intestinal villi — tiny hair like structures in the wall of the small intestine.

In addition, both the small intestine and colon were longer in the old mice than the young germ-free mice.

The discovery shows that gut microbes can compensate and support an ageing body through positive stimulation.

This points to a new potential method for tackling the negative effects of aging by imitating the enrichment and activation of butyrate, the researchers said.

“We can conceive of future human studies where we would test the ability of food products with butyrate to support healthy aging and adult neurogenesis,” said Pettersson. (AGENCIES)