Ravinder Kaul

The moment I open the book and my eyes rest on the first lines ‘They found the old man dead in his torn tent, with a pack of chilled milk pressed against his right cheek. It was our first June in exile, and the heat felt like a blow in the back of the head’, a lump is formed in my throat. My eyes feel moist. It is with a great effort that I keep reading. But, after a while, it becomes too painful to continue. Even turning a page seems like a herculean task. I feel drained both emotionally and physically. I give up.

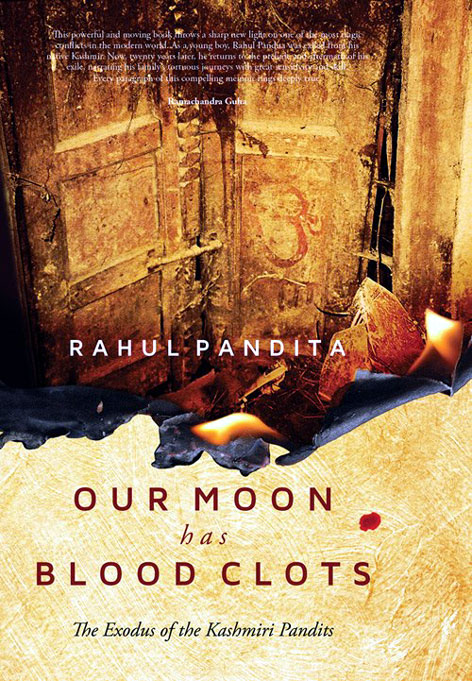

The lump returns even a few hours later as I pick the book again. It takes me almost a week to go through the 258 pages of Rahul Pandita’s immensely readable book ‘Our Moon has Blood Clots’-The Exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits.

The reason for the slow pace of reading is that it is an extremely disturbing book, particularly for those who have experienced the trauma of leaving their home under duress. Although the book is essentially about the circumstances and the manner in which Kashmiri Pandits were forced out of their homes in the year 1990, any individual or community that has had to leave home under similar circumstances will relate to it.

The author, Rahul Pandita has just crossed the threshold of going into the deep side of his 30s but he is already a veteran journalist. His particular area of expertise is conflict zones. It is a personal memoir about his exodus from Kashmir in 1990, along with about 3.5 lakh members of the Kashmiri Pandit community. He was just 14 years old.

Two facets strike one about Rahul’s personality as an author, his professionalism as a journalist and his love for literature. The book beautifully blends both sides of this persona, presenting a literary masterwork on a much higher plane than mere reportage. While he clinically presents the historical background of the Kashmir conflict and details of sufferings of the Kashmiri Pandit community, the style and usage of language is sheer poetry. It is actually a requiem for a decimated community, a lifestyle, a culture and a people. A few examples are to be savoured:

About a distant cousin who committed suicide while the author was still in Srinagar:

‘Her death left some indelible mark in my heart, some sort of pain-as if she had jumped into the Jhelum to meet me, and I was not there to save her, to rescue her. She must have been very lonely, or in love, or both…..Her memory always makes that dull throbbing pain return-the pain of being in exile.’

About how India’s loss to Pakistan in a cricket match at Sharjah in the year 1986 left a permanent scar on the author’s adolescent psyche:

‘Twenty-five years later after that episode, in 2011, when we had been in exile for more than two decades, India registered a World Cup victory. I am grown up now, and victory or defeat in a cricket match means nothing to me. But my father had tears in his eyes when India won. He looked at me expectantly. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that though I don’t care any longer for cricket, my feelings from 1986 remain. In ‘More Die of Heartbreak’, Saul Bellow calls such feelings ‘first heart’. My first heart remains with that failed Yorker bowled by Chetan Sharma.’

About the author’s visit to the house that was once his home in Srinagar and which had been sold during exile:

‘…I look at the spot where the apple tree used to be. I remember how Dedda used to sit there or how Totha would take me there and try to keep me busy playing with pebbles…….’There used to be an apple tree there,’ I point with my finger. ‘Oh, we got it cut; it was occupying too much space.’ Ghulam Hasan Sofi’s voice rings in my ears-

B’e thavnus chaetit tabardaaran

Yaaro wun baalyaaro wun

Chh’e kamyu karenai taavei’z pun?

I was split apart by the woodcutter

My friend, my beloved, tell me:

Who has cast a spell on you?’

About the effects of killing, by militants at Gool in the year 1997, of the author’s favourite cousin Ravi, ‘my brother, my first hero’, to whom the book is dedicated:

‘Ravi is dead. Life is empty. Family is meaningless. Ma never recovers. I think it is from that moment onwards that she began to slip away. Ravi’s father never recovered. He kept saying ‘Ye gav mein kabail raid’e’-this is my personal tribal raid.’

No detail escapes the keen journalistic eye of the author. He catches the tragedies, the ironies and the farce of various situations with finesse and sensitivity. The picture of a Jewish prisoner in Auschwitz, which the author sees in Delhi long after his forced exile, reminds him of the stark blankness in the eyes of a woman he had seen peeping out of the tarpaulin sheet of a truck at Ramban when he, along with other Kashmiri Pandits, was fleeing Kashmir. Her eyes ‘were like a void that sucked you in’, he recalls. Sitting in a television news studio in Delhi while discussing the killing of Muslims in Ahmedabad by a Hindu mob, the author confronts an ‘uproariously drunk’ army general who questions his stand on zero tolerance towards such crimes saying ‘it is they who have forced you out of your homes’, with the calm retort ‘General, I’ve lost my home, not my humanity’.

Kashmiri Pandits are nowhere men who are not considered worthy of even lip sympathy anymore. The political class has abandoned them for they are not a vote bank and do not possess the capability to swing results in any constituency. Their plan for return is in a shambles and the government does not appear to have either the will or the inclination to seriously implement any roadmap for their permanent return to the Kashmir Valley. Rahul has visited the resettlement colonies, ironically conceived like ghettoes, constructed in Kashmir (Sheikhpora and Vessu) and Jammu (Jagti) and considers these as glaring symbols of the apathy of the administration towards Kashmiri Pandits. The community has also been abandoned by the intellectual class and the media which, while highlighting the ‘brutalisation of Kashmiri Muslims at the hands of the Indian state …failed to see, and has largely ignored the fact that the same people also victimised another people’. ‘It has become unfashionable to speak about us, or raise the issue of our exodus’, he concludes.

Yet, Rahul Pandita has not given up hope. In the concluding words of the book he writes, ‘I will come again. I promise there will come a time when I will return permanently’. It is this optimism and the refusal of the author to succumb to cynicism despite grave tragedies that distinguishes this book from scores of other books dealing with contemporary history of Kashmir. Albert Einstein had said ‘Few people are capable of expressing with equanimity opinions which differ from the prejudices of their social environment. Most people are even incapable of forming such opinions’. One must admit, after reading the book, that Rahul Pandita is among few such people who have successfully achieved this delicate balance.

The book is a must read for all students of recent history of Kashmir and for everyone who or whose forefathers have ever suffered the pangs of forced migration. The book must find a place in every Kashmiri Pandit household and must be handed down as a family heirloom so that the future generations of Kashmiri Pandits, born and brought up in exile, do not forget how their ancestors were forced out of Kashmir, their motherland. The title of the book is taken from a poem of Pablo Neruda that the author quotes in the beginning of the book ‘…and an earlier time when the flowers were not stained with blood, the moon had blood clots!’

Trending Now

E-Paper