Harihar Swarup

The year, 2020, needs no introduction, neither does Sonu Sood. When the year kept throwing challenges at us, he inspired us to face them with kindness and compassion .The work that stood out was the Ghar Bhejo campaign to send migrants home and bring stranded Indian students home back. Sood has received both bouquet and brickbats. But he remained unfazed. He has been rightly adjudged THE MAN OF THE YEAR 2020.

It was day three of the lockdown, Mumbai, always bursting at the seams, found itself straitjacketed, or so it seemed; its crowded, chaotic streets almost deserted and quiet.

Actor Sonu Sood and his childhood friend Neeti Goel were heading home after distributing food to homeless who had found shelter under the Eastern Express Highway. While driving through Bandra, they saw a woman bent over a stove, stirring an empty vessel. As the car drove past, the woman ran towards it, waving frantically to stop. When Sood and Goel stepped out of the car, the woman broke down. She showed them the pot. It was empty, save for some stones. Shantabai had been stirring an empty vessel so that her five children-aged between one and seven-would fall asleep in the false hope that food would be served soon.

Shantabai’s situation left Sood feeling hollow. He realised that her plight was shared by many daily wage earners who were jobless because of the lockdown. The thought that thousands of children were going to bed hungry kept him up at night. He decided he had to do something. What followed was an outpour of compassion.

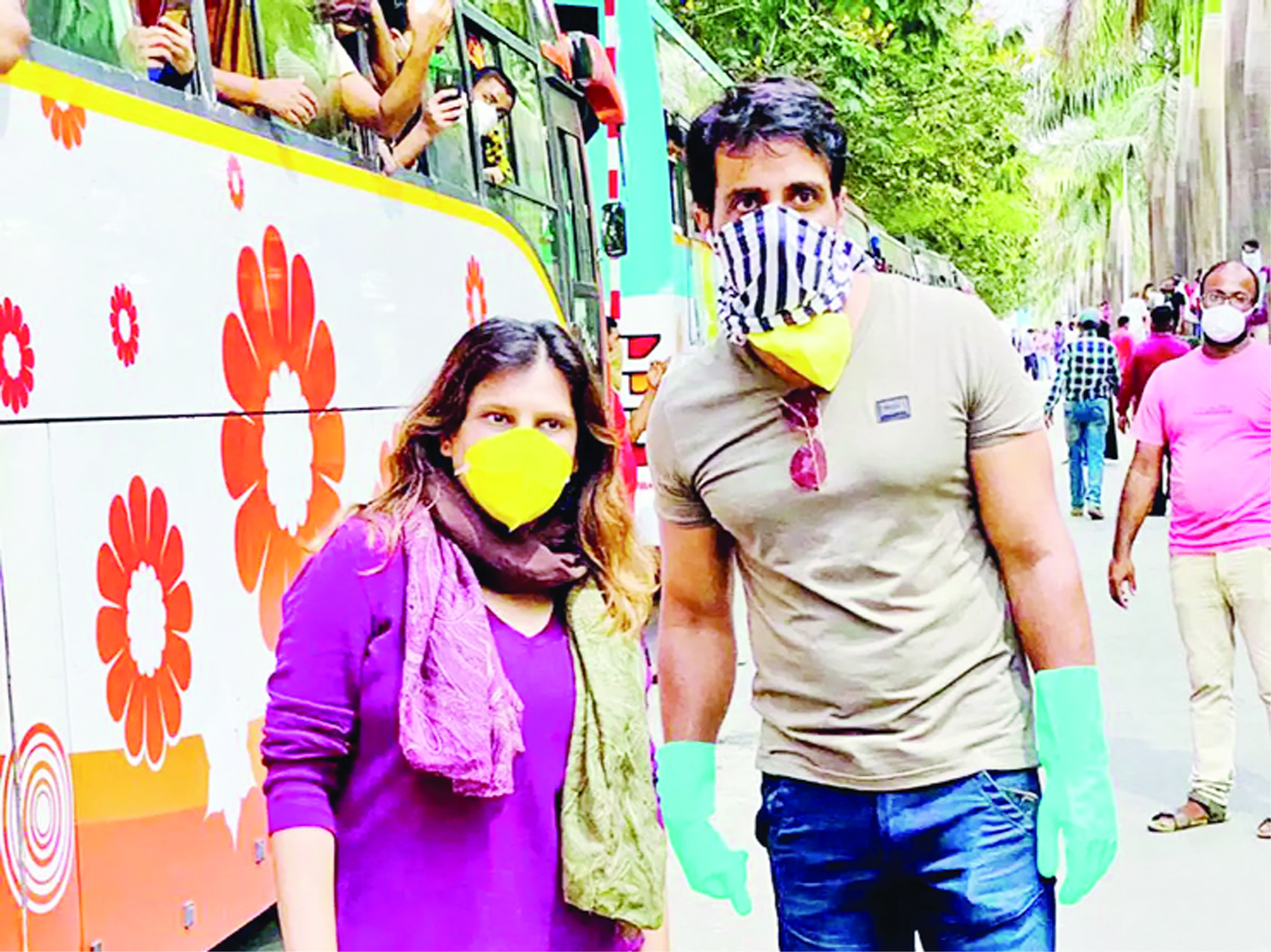

In April and May, as the lockdown kept extending, desperate migrants started walking home. Sood launched the Ghar Bhejo campaign with Goel, and reportedly arranged transport for 7.5 lakh migrant workers. He equipped frontline workers with masks and face shields, airlifted students stranded abroad and helped farmers in distress. He also launched Pravasi Rojgar, an app to help skilled and unskilled workers find jobs.

While showing kindness comes easy to some, it does take great effort. For instance, Ghar Bhejo was launched at a time when even cycles stayed off roads. Sood and his friends approached many people to ferry the migrants. Bus owners refused, fearing that their vehicles would be vandalised. Finally, someone with a fleet of 120 buses pitched in. Sood promised to reimburse him for any loss or damage to the buses.

Getting permission was a big challenge, said Sood. “All those stranded would connect with me on social media, especially on Twitter,” he said. “I had to take permissions for every single individual who was travelling.” Sood said he would make a list of all those who contacted him, and divide them into groups. “I made a few people head each group, got details of each person travelling in that group and then sent requests to authorities of respective states for permissions,” he said. He also had to take travel permits for every bus driver.

Procuring medical certificates was another herculean task. Covid-negative reports were mandatory for interstate travelers, and Sood had to coordinate with doctors, too. “I hardly slept in the first week as the whole country was chasing me to help them go home,” he recalled. People close to him said that the 47-year-old worked for 20-22 hours a day to get the first set of buses moving.

Sood arranged buses for migrants from Mumbai to travel home to Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, Tamil Nadu and Akola in Maharashtra. Some migrants in Kerala and Mumbai were airlifted and sent home to Bhubaneswar, Uttarakhand and Assam.

Among those who benefitted from GharBhejo project is a plumber from Varanasi who needed an emergency kidney transplant. He insisted on going back home as he did not want to die in Mumbai. Sood and his friends organized an ambulance for him with great difficulty. They got him admitted to a hospital in Varanasi and ensured that he had the transplant.

The migrant crisis unleashed by the lockdown forced around 30 million people – 15 to 20 per cent of the urban workforce – to eventually go home, said Chinmay Tumbe, assistant professor, economics, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. “Sood’s empathy and service shone through brilliantly in those times as middle and upper class urban India turned its back to the crisis, comfortably watching returns of epics on TV,” said the author of India Moving: A History of Migration.

Sood’s wife, Sonali, said that the migrant crisis took an emotional toll on him. “He interacted with people closely and saw their pain, which affected him quite a bit,” she said. “He was constantly working those days. Sometimes he would get up at 3am and respond to requests on Twitter. He did it with so much dedication and sincerity.”

Initially, Sood and Goel only had about six people assisting them for the Ghar Bhejo campaign; today they have a 90-member team. “The campaign started with me and Sonu funding it personally, as no one believed in it,” said Goel. “But, later people came forward and supported us.”

Shamid Ali, 27, would vouch for the work done by Sood and his team. Beebi, his one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, had a hole in the heart and required an open-heart surgery. Ali, a truck driver from Karnataka’s Kanakagiri, reached out to Sood’s team. He was surprised when the actor answered the phone. “He asked me to come to Mumbai with my family,” said Ali. “We met Sood sir at his home. He gave us food.”

Sood connected Ali with SRCC Children’s Hospital. “We love Sonu sir very much. It is not enough to call him god” said Ali, in a trembling voice. His prayers now include a plea for Sood’s well-being. He shares video clips of his daughter and voice messages with Sood, who promptly replies to them. (IPA Service)

Trending Now

E-Paper