LONDON: Scientists have decoded how the bronze weapons of China’s iconic Terracotta Army remained pristine and shiny despite being buried for nearly 2,000 years.

The team found that the chrome plating on the Terracotta Army bronze weapons — once thought to be the earliest form of anti-rust technology — derives from a decorative varnish rather than a preservation technique.

The study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, reveals that the chemical composition and characteristics of the surrounding soil, rather than chromium, may be responsible for the weapons’ famous preservation power.

“The terracotta warriors and most organic materials of the mausoleum were coated with protective layers of lacquer before being painted with pigments — but interestingly, not the bronze weapons,” said Marcos Martinon-Torres, from University of Cambridge in the UK.

“We found a substantial chromium content in the lacquer, but only a trace of chromium in the nearby pigments and soil — possibly contamination,” Martinon-Torres said in a statement.

“The highest traces of chromium found on bronzes are always on weapon parts directly associated to now-decayed organic elements, such as lance shafts and sword grips made of wood and bamboo, which would also have had a lacquer coating,” he said.

“Clearly, the lacquer is the unintended source of the chromium on the bronzes — and not an ancient anti-rust treatment,” he added.

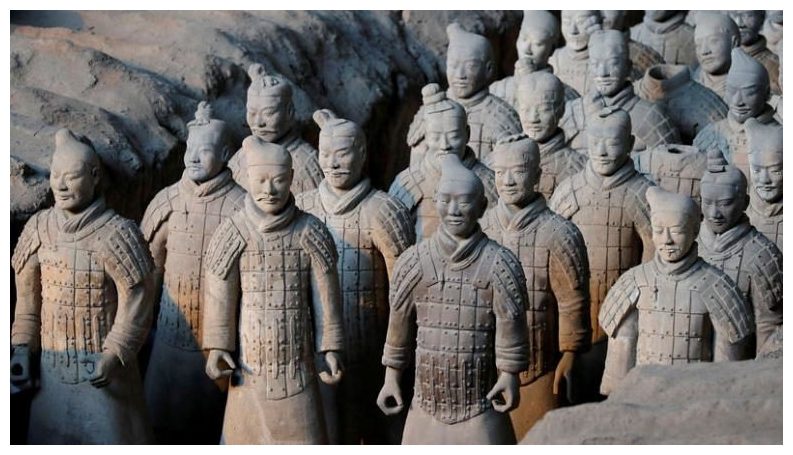

The world-famous Terracotta Army of Xi’an consists of thousands of life-sized ceramic figures representing warriors, stationed in three large pits within the mausoleum of Qin Shihuang (259-210 BC), the first emperor of a unified China.

These warriors were armed with fully functional bronze weapons; dozens of spears, lances, hooks, swords, crossbow triggers and as many as 40,000 arrow heads have all been recovered.

Although the original organic components of the weapons such as the wooden shafts, quivers and scabbards have mostly decayed over the past 2,000 years, the bronze components remain in remarkably good condition.

Since the first excavations of the Terracotta Army in the 1970s, researchers have suggested that the impeccable state of preservation seen on the bronze weapons must be as a result of the Qin weapon makers developing a unique method of preventing metal corrosion.

Traces of chromium detected on the surface of the bronze weapons gave rise to the belief that Qin craftspeople invented a precedent to the chromate conversion coating technology, a technique only patented in the early 20th century and still in use today.

Researchers showed that the chromium found on the bronze surfaces is simply contamination from lacquer present in adjacent objects, and not the result of an ancient technology.

“Some of the bronze weapons, particular swords, lances and halberds, display shiny almost pristine surfaces and sharp blades after 2,000 years buried with the Terracotta Army,” said Xiuzhen Li from University College London in the UK.

By analysing hundreds of artefacts, researchers also found that many of the best preserved bronze weapons did not have any surface chromium.

To investigate the reasons for their still-excellent preservation, they simulated the weathering of replica bronzes in an environmental chamber.

Bronzes buried in Xi’an soil remained almost pristine after four months of extreme temperature and humidity, in contrast to the severe corrosion of the bronzes buried for comparison in British soil.

“It is striking how many important, detailed insights can be recovered via the evidence of both the natural materials and complex artificial recipes found across the mausoleum complex — bronze, clay, wood, lacquer and pigments to name but a few,” said Andrew Bevan, from UCL.

These materials provide complementary storylines in a bigger tale of craft production strategies at the dawn of China’s first empire,” said Bevan. (AGENCIES)