Amardeep Singh

Postman to my father, “Sunder Singh, this is a strange postcard and I believe it is for you.” With a two line address that just read “Sunder Singh, Gorakhpur,” it could only be a divine intervention that the postcard sent from Rawalpindi (Pakistan), found it’s way to my father in Gorakhpur (India).

In a crippled handwriting, it’s content was nothing else but an address of a Christian Missionary base in Rawalpindi, followed by the name “Hari Singh.” Just like the concise address, it’s content didn’t say much.

This was a moment of joy that Sunder Singh could not express any better but by letting the tsunami of tears roll down his cheeks. He rushed to the thatched hut at a short distance from his home. It was the sultry summer of 1949 and he was thankful to God that in the last two years, life was slowly limping back to normal for his siblings, who had moved to the city of Gorakhpur (Uttar Pradesh, India). In the pogrom conducted against non-Muslims in the city of Muzaffarabad (now in Pakistan Kashmir), his siblings had lost everything.

Wealth comes and goes but can life be replaced?

No mother can part with her children but when Pashtun tribals from Waziristan and adjoining areas entered Kashmir with an objective to cleanse the non-Muslim population and thereby occupy the region for the newly formed Pakistan, Sunder Singh’s sister was then in Muzaffarabad. The attackers parted women from men and children from women. The intent was to take into custody the young girls and shoot the adult males. Helpless, she had no clue what happened to her two boys, as much as they about their mother.

Sunder Singh pushed the door open and entered his sister’s hut, “Bhen (sister), I think the children are alive!”

My father, a goldsmith by profession from the region of Muzaffarabad, had left for Gorakhpur in 1945 to explore new business opportunities associated with supply of gold jewelery to the Gurkhas of British India army. The Gurkhas from Nepal would arrive at Gurkha Regiment Depot to collect their pension and this presented an opportunity as many would convert cash into gold, before heading back to their villages. In the two years prior to partition of India, Sunder Singh was busy setting up a business in Gorakhpur and his presence in a distant land became the reason why his siblings chose this city for migration.

In the religion based partition of August 1947, Pakistan was formed with Islamic foundation, while India maintained an all inclusive religious position. It triggered violence across communities on both sides of the dividing line. The outcome was that Sikhs and Hindus got cleansed from West Punjab and the now Pakistan Administered Kashmir.

Kashmir was not included in the state of Pakistan as the option to join or remain independent was left for the ruler, Hari Singh. While he delayed the decision, in mid October 1947, Pashtun tribals from Waziristan and Khyber region attacked Kashmir, in order to force it to join Pakistan. On 21st & 22 October, over 300 male Sikhs from the surrounding valleys were rounded up at Ranbir Singh bridge (also called DUMEL bridge as the rivers Jhelum and Neelum/ Kishenganga rivers join close to it) in Muzaffarabad and shot by the tribals at a point blank range.

Sunder Singh was helpless, stranded in Gorakhpur but it was also a blessing in disguise for his siblings, who saving their lives headed from Muzaffarabad to Baramulla and thereon to the valley of Srinagar.

In the months that followed, Sunder Singh was in turmoil, leaving the business activities behind he left for Delhi in hope to somehow reunite with his family. For three months he spent day and night at the Delhi Airport, sending messages through any defence personnel traveling to Srinagar. Luck would have it that one army man was able to locate his brother, Amar Singh and got back a message for Sunder Singh. My father spent his resources in reuniting the family by bringing them to Delhi. It was in December of 1947 an army Dakota plane carrying some refugees landed in Delhi and it included my father’s siblings. This was a moment to celebrate but there was also an intolerable pain as one of his sister did not know what may have happened to her two boys, aged less than 10 years. The two lads, Arjan Singh and Hari Singh, on being caught by the tribals were put through mental and physical humiliation. For Sikhs, keeping unshorn hair is the most sacred requirement and the tribals first action was to deprive them of this visible sign of their faith. For days they lived in fear of the unknown and being taken away from their loved ones. Finally, when the 1st Sikh regiment of the Indian army advanced and pushed the tribals back, they abandoned the children and left with looted wealth.

A Christian missionary outfit from Rawalpindi reached Muzzafarabad in November 1947 and took custody of the two destitute boys.

Time does not stop for anyone. Sunder Singh stabilized his uprooted brothers and sisters in Gorakhpur, helping them start their life from scratch but was always concerned about the well being of his sister who was under emotional pain of separation.

Strange are God’s ways for whom he desires to save. Even in a whirlpool, he leaves a twig to hold. As a young boy of around 7 years, Hari Singh had heard his mother often say that his Mama (Uncle), Sunder Singh has gone to Gorakhpur. Somehow in October 1949, Hari Singh managed to source a postcard and sent it by addressing to “Sunder Singh, Gorakhpur “, mentioning the address of the Rawalpindi Christian missionary.

The postcard did reach the hands of my father. This could only happen with divine intervention.

The challenge now was that the borders of the two nations were sealed. Travel to Rawalpindi to rescue the children was impossible. Sunder Singh headed to Delhi to leverage political strings. He met with Baldev Singh, the first Defence Minister of India, requesting his intervention.

Files moved across the borders and a few months later, the children were united with their mother.

Though I was born in the year 1966, nineteen years after partition but I grew up amongst such real lifetime stories. With passage of time the footprints have only grown bigger and were demanding a closure.

I grew up delving into the history of my community and realized that 80% of the Sikh heritage lies in the area that now falls in Pakistan, and post partition it is lost forever. It is with this backdrop, I had told myself that once in my lifetime, I will travel freely in Pakistan. Our next generation may not be able to associate closely with the events of partition but at least for me, the entire being desired to feel the energy of our ancestors.

In October 2014, at the age of 48 years, I was finally able to make the trip. In a backpacking style I traveled for 30 days, exploring the Sikh heritage that now lies in dilapidated condition across remote areas, unprotected and soon to become extinct. I visited the non-functional Gurudwaras in villages, forts, schools and more importantly met people who once had a Sikh lineage but had to convert their faith in order to survive.

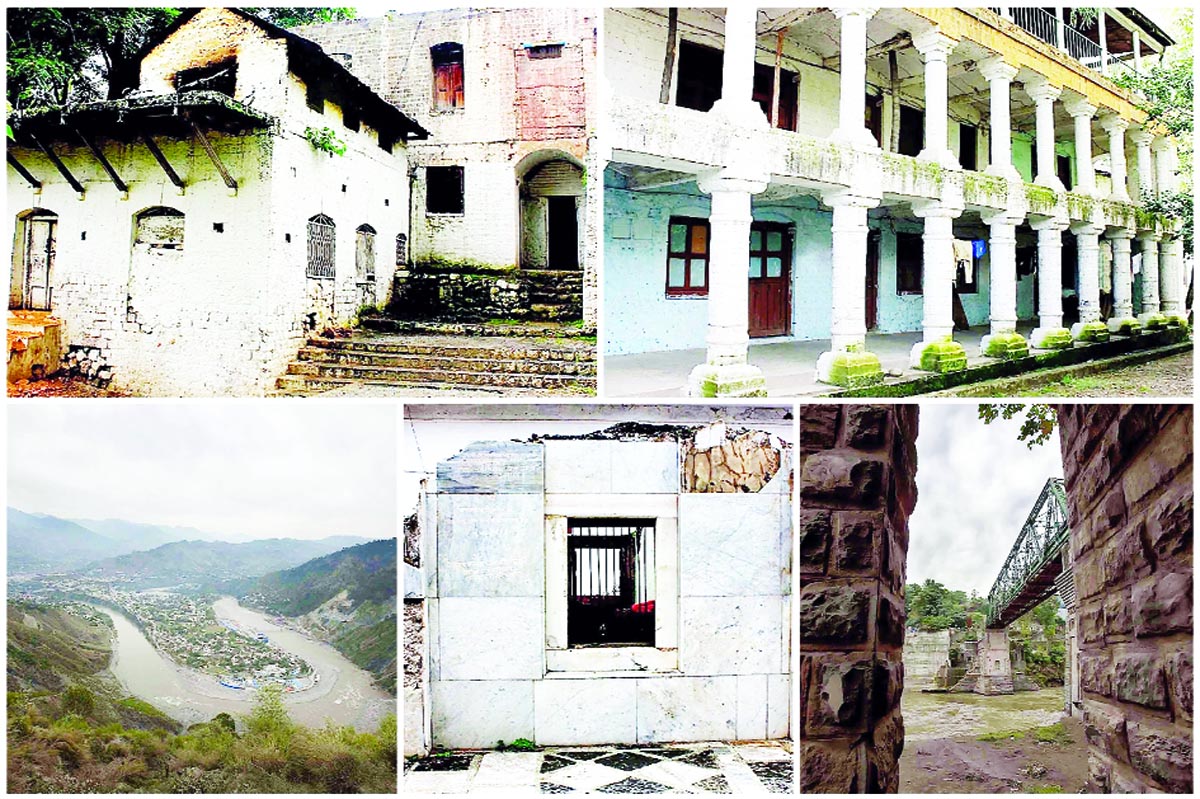

Though I travelled extensively across Punjab, Khaibar and Pakistan Administered Kashmir but I knew the attraction of the trip was a visit to Muzaffarabad, the place where our paternal family hailed from. Driving from Abbottabad, I entered Pakistan Administered Kashmir, and the first glance of the city of Muzaffarabad from the top of the hill, peaked my emotions to a level that I had to ask the driver to halt the car. As I stood by the road, looking into the vast expanse of the valley, the meandering Jhelum river making a U-turn, I was asking myself, “is this the expanse of the valley that my father used to describe. He used to describe a small Shangri-La (a heavenly valley) but this is just like any other modern city.” Seeing the development it didn’t resonate with the image that I was carrying of the valley in my memory, but time has neither stopped. It is 67 years since partition and the valley has naturally expanded. Muzaffarabad is located on the banks of Jhelum and Neelum (Kishanganga) rivers. It is bordered by Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa in the west, by the Kupwara and Baramulla districts of Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir in the east, and the Neelum district of Pakistan Admnistered Kashmir.

See Fulltext: https://www.dailyexcelsior.com/sunday-magazine/

Guru Hargobind, the 6th Guru had visited the valley and many residents had thereafter adopted Sikhism. Prior to partition the valley of Muzaffarabad and adjoining areas of Balakot and Ramkot consisted of a large Sikh population. The historical Gurudwara in the memory of Chatti Pathshahi (Guru Hargobind’s visit) used to be a fulcrum where the Sikh population of the valley would come together. Today, the Gurudwara premise is converted into a Police station and a CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) establishment. The north wall of the Gurudwara building is all that remains of the main structure as it has been reconstructed into the new establishment building. The resident hall and the kitchen areas of the Gurudwara area are though surviving and being used as residence.

As we were parking the car in the market, a man approached asking in Punjabi, “Sardar Ji, what brings you to Muzaffarabad?”

We struck a conversation and he shared that he belonged to a nearby village. He had heard stories from his parents about the vibrant Sikh community that had existed in this region, scattered across remote villages. He offered to take me to his village where he can point to the houses which once belonged to the Sikhs and are now occupied by the local Muslim community. He shared an interesting observation that many Sikhs leaving Muzaffarabad had buried their valuables under the cooking area of the kitchen or in the walls. So years after 1947 migration, the occupiers of residences would continue to dig the kitchen area and break the walls in search of valuables and many did succeed. Going to his village would have required about 4 hours and therefore I politely requested to be excused.

At the Dumel bridge (Ranbir Singh bridge), the site with which many stories are associated with our extended family, we have grown up hearing, I became highly emotional. My mother-in-law, Satwant Kaur, who stays in Dehradun had also lost both her parents in the target Sikh killings conducted on this bridge by the attackers.

At the bridge, I took the stairs and headed down to the river bank, standing in silence, hearing the gushing water.

A stone slab with the year 1885 indicates this bridge has been standing for 130 years. It is named after the Dogra King, Ranbir Singh of Jammu & Kashmir state.

The structure of the bridge and the existence of a Baradari (structure with twelve gates) at the lower section, with nearly extinct ghat structures indicates the prominence of this place for the Hindu community of the region, akin to the ghats of Varanasi. This bridge is the only footprint of the secular civilization that once co-existed.

When I was planning for the Pakistan trip, a strong desire had manifested my being that I need to carry back the soil of Muzaffarabad from under this bridge and preserve it in a sealed bottle to pass on to next generation as a reminder of the holocaust. However as I stood here, I seemed to have a numb feeling. The valley did not resonate with the picture that I had created for myself. The people were not approachable, primarily because of my own perception that as a lone Sikh, I may be under risk. The bridge gave me a creepy sense of the past.

Suddenly, I decided I didn’t want to spend a minute more in Muzaffarabad. Hurriedly I climbed the stairs, got into the car and we were off to Murree in Punjab. I did not have any more desire to explore the valley and neither to carry back any soil.

The closure I had been seeking in my mind happened with the acceptance that things have changed and I need to move on in life.

Trending Now

E-Paper