Ashok Ogra

In his autobiography ‘I Have the Streets: A Kutty Cricket Story’, leg-spinner Ravichandran Ashwin makes an intriguing observation: “Players who don’t know Hindi will find the dressing room environment of Indian teams, especially in junior cricket (Under-15 and Under-17), forbidding and unwelcome.”

He further adds that while opposing Hindi can be a form of protest, it may also mean missing out on opportunities for growth.

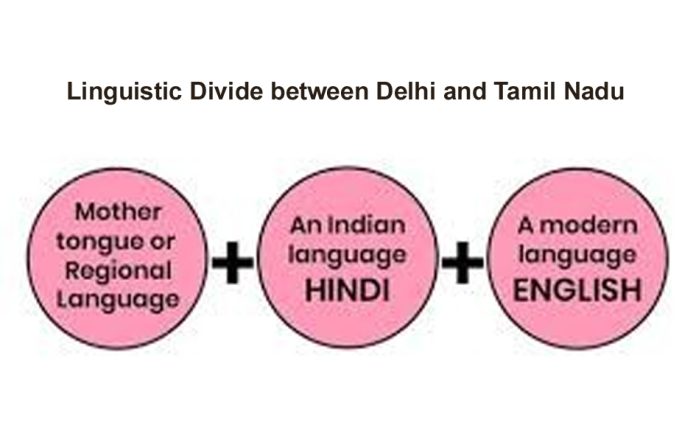

This raises an important question: why is the Tamil Nadu government adamant about offering only two-languages to the school students and strongly opposing the three-language formula outlined in the New Education Policy (NEP) 2020? By doing so, is it denying its own students the opportunity to embrace India’s linguistic diversity, and thus compete more effectively in other states?

Interestingly, despite Tamil Nadu’s official stance, hundreds of CBSE-affiliated schools and Kendriya Vidyalayas in the state offer Hindi as a third language. However, thousands of schools under the state board do not extend this option to their students.

Lack of Reciprocity in Language Learning:

This linguistic divide is not a one-way street. One of the major grievances of non-Hindi-speaking states is the lack of reciprocity in language learning. In Delhi, for instance, government schools-including Kendriya Vidyalayas-do not offer Tamil, Telugu, or even Bengali, despite significant populations from these linguistic backgrounds. Until the late 1980s, Tamil speakers had a strong presence in Karol Bagh, yet no school in the area offered Tamil as a subject.

While NEP 2020 technically does not impose any specific language, allowing states and students to choose so long as two languages are Indian, concerns about Hindi dominance persist. The 2019 Union Budget’s allocation of ?50 crore to support the appointment of Hindi teachers in non-Hindi-speaking states has only deepened these fears.

Meanwhile, Tamil Nadu has refused to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the PM Schools for Rising India (PM-SHRI) scheme, arguing that it could lead to the imposition of Hindi. In response, the Union government has withheld over ?2,000 crore in funding under the Samagra Shiksha scheme. This has escalated tensions, with BJP leaders accusing Tamil Nadu of defying the Constitution, while the Tamil Nadu government argues that the Centre is undermining linguistic and cultural autonomy.

One must add here that the state elections are due later this year, therefore, we should expect more such noise – some genuine but most of it to appeal to DMK’s voter base.

A Deep-Rooted Divide:

This disagreement reflects a broader communication breakdown between two democratically elected governments, particularly since the BJP assumed power in 2014. While the BJP positions itself as a custodian of national unity, the DMK-led Tamil Nadu government views many central policies with suspicion. The situation is further exacerbated by the actions of Tamil Nadu’s Governor, whose perceived partisanship has fueled tensions.

Linguistic assimilation in India has historically been organic. Communities have adapted to local languages while retaining their cultural identities. The Parsi community, for example, adopted Gujarati after migrating in the 8th century, developing a distinct dialect known as Parsi-Gujarati.

Similarly, Chakradhar Swami, the founder of the Mahanubhava sect, encouraged his followers to write in Marathi after migrating from Gujarat to Maharashtra in the 13th century.

Post-independence, India grappled with two major linguistic challenges: state reorganization along linguistic lines and the selection of a national language. Leaders like Nehru, Patel, and Dhulekar advocated for Hindi, but figures such as Rajagopalachari and Chettiar feared that it would marginalize regional languages.

Dr. Ambedkar proposed continuing English as a neutral language that belonged to no specific region. The eventual compromise -known as the K.M. Munshi-Gopalaswamy Aiyangar formula-declared Hindi as the official language while allowing English to remain an associate official language for 15 years. However, the planned transition to Hindi did not materialize as expected.

In 1965, the central government’s attempt to make Hindi the sole official language triggered violent protests in Tamil Nadu. The DMK-led agitation echoed earlier resistance in 1937, when the Madras Presidency opposed the British administration’s move to introduce compulsory Hindi in schools. The protests forced the Centre to retreat, leading to a revised policy that allowed English to continue indefinitely as an associate official language.

Interestingly, socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia argued that India’s richness lay in its languages. He emphasized that language is central to people’s identity and warned against imposing a single linguistic order.(Rural India: The Real India by Ram Manohar Lohia)

The One-Way Engagement in Literature:

The imbalance in linguistic engagement is also evident in literature. While many Tamil writers have contributed to Hindi literature, Hindi-speaking writers rarely engage with Tamil literature. Similarly, Punjabi writers have extensively written in Hindi, but the reverse is uncommon.

The dominance of standardized Hindi at the expense of dialects like Bhojpuri, Maithili, and Awadhi further underscores the homogenizing tendencies in India’s language policies.

Global Parallels in Language Conflicts:

The politics of language is not unique to India. In Pakistan, the imposition of Urdu on Bengali speakers in East Pakistan led to protests in 1952, eventually culminating in the creation of Bangladesh in 1971.

In Sri Lanka, the 1956 decision to make Sinhala the sole official language alienated the Tamil-speaking population and fueled a decade-long civil war.

Spain has seen long-standing tensions between the central government and Catalonia over linguistic identity. Canada’s French-speaking province of Quebec has frequently clashed with the English-speaking federal government over language rights.

Recent Flashpoints in India:

In 2017, the Centre proposed making Hindi mandatory for central government job recruitment, reigniting concerns in non-Hindi-speaking states. The inclusion of Hindi in the NEET medical entrance exam, while excluding regional languages, further exacerbated these anxieties.

National Unity and Linguistic Diversity:

It must be appreciated and acknowledged that English has remained a neutral linguistic bridge across states and continues to serve as a unifying force- even when Indian languages continue to grow in their respective regions.

Tagore believed that India’s various languages represented the vibrancy of its culture and should be preserved as an asset to the country’s collective identity.

Interestingly, traders and businessmen – Marwaris, Sikhs etc- who migrated to other states decades ago have embraced the local language and culture. The famous Marwari, Jyoti Prasad Agarwal made significant contribution to Assamese literature and culture, producing and directing the first Assamese film ‘JOYMOTI’ in 1935.

The fact remains that many Tamilians in Delhi have learned Hindi for daily interactions, adapting to its spoken form even if they retain a Tamil accent. Remember the familiar DD national network Hindi newscaster J.V.Raman who was a Tamilian. Or look at the Tamilians who quickly learn Hindi when they join the Indian Army.

The same should be expected of the thousands of migrants from the Hindi heartland who move to southern states for employment-learning the local language should be a natural step, even if office communication remains in English.

A Call for a Broader Perspective:

Perhaps, as my friend Atulit Saxena puts it, we need to rethink the very concept of language. Beyond linguistic divides, what about the universal languages of hygiene, sports, technology, and the arts-essential skills for nation-building?

How does India become a Vishva Guru by 2050 if one goes by the Annual Status of Education Research (ASER) 2020? The report indicates that close to 60% of students in Class V could not read a Class II level text; 25% of 14-18 years old could not read a Class II level text fluently in their regional language. More than 40% of this age group could not read sentences in English.

We have government schools without teachers, teachers assigned to schools that exist only on paper, and in cases where both teachers and schools are present, no teaching actually takes place.

Therefore, the debate ought not to be confined to how many languages one studies in school but the focus should be on teaching and learning. Imagine, there are 5000 schools in UP that have just one teacher across all subjects. The situation in Bihar is even worse.

Regardless, the need of the hour is to bridge the gap between ‘big brother’ Delhi and ‘obstructionist’ Chennai, and by extension, between other state capitals. The continuing stalemate not only undermines but also denies students the opportunity to learn a third language – a point Chennai based cricketer Ashwin laments in his autobiography!!!

(The author works for reputed Apeejay Education, New Delhi)

Trending Now

E-Paper