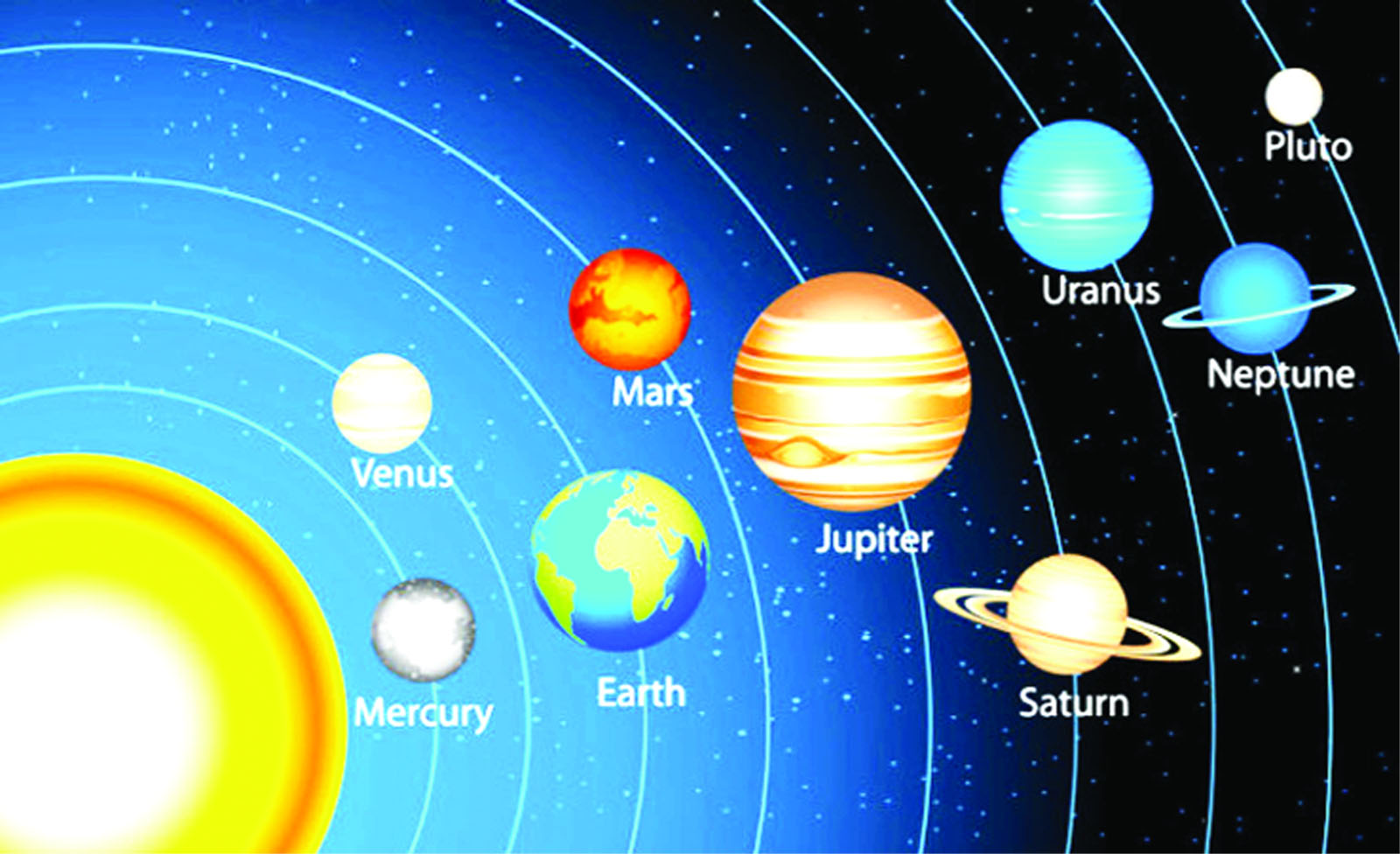

From Mercury, the planet closest to the Sun, to the icy dwarf Pluto, scientists this year explored far reaches of our solar system, travelling unprecedented distances to make new discoveries and solve many mysteries of the vast space surrounding the Earth.

“This past year marked record-breaking progress in our exploration objectives,” said NASA Administrator Charles Bolden.

A newly discovered “great valley” in the southern hemisphere of Mercury provided more evidence that the small planet closest to the Sun is shrinking.

Scientists used stereo images from NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft to create a high-resolution topographical map of Mercury that unveiled the broad valley – more than 1,000 kilometres long – extending into the Rembrandt basin, one of the largest and youngest impact basins on the innermost planet of our solar system.

About 400 kilometres wide and three kilometres deep, Mercury’s great valley is larger than North America’s Grand Canyon and wider and deeper than the Great Rift Valley in East Africa.

In July, scientists using observations from European Space Agency (ESA)’s Venus Express satellite, showed for the first time how weather patterns seen in the planet’s thick cloud layers are directly linked to the topography of the surface below.

Rather than acting as a barrier to our observations, Venus’ clouds may offer insight into what lies beneath.

Frozen beneath a region of cracked and pitted plains on Mars lies about as much water as what is in Lake Superior, largest of the Earth’s Great Lakes, researchers using NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter determined.

This reserve could prove to be a vital resource for astronauts in future manned-missions to the red planet.

“We advanced the capabilities we will need to travel farther into the solar system while increasing observations of our home and the universe, learning more about how to continuously live and work in space, and, of course, inspiring the next generation of leaders to take up our Journey to Mars and make their own discoveries,” Bolden said. Meanwhile, ESA’s Schiaparelli – an entry, descent and landing demonstrator module launched in March – failed to successfully land on the surface of Mars. The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) which carried the test lander continues to orbit the red planet.

The ExoMars programme will continue to investigate the Martian environment and findings may pave the way for a future Mars sample return mission in the 2020’s.

After a five year long journey, NASA’s solar-powered Juno Spacecraft entered Jupiter’s orbit on July 5. It became humanity’s most distant solar-powered emissary. The milestone was achieved on January 13, when Juno was about 793 million kilometres from the Sun. In August, the probe successfully executed its first of 36 orbital flybys of the ‘King of planets’ passing about 4,200 kilometres above Jupiter’s swirling clouds – the closest Juno will get to Jupiter during its prime mission.

Meanwhile, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope imaged what may be water vapour plumes erupting off the surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa.

The observation increases the possibility that missions to Europa may be able to sample Europa’s ocean without having to drill through miles of ice.

After more than 12 years studying Saturn, its rings and moons, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft entered the final year of its voyage.

On November 30, Cassini began orbiting just past the outer edge of the main rings, executing the first ring-grazing plunge on December 5.

These orbits, a series of 20, are called the F-ring orbits. During these weekly orbits, Cassini will approach to within 7,800 kilometres of the centre of the narrow F ring, with its peculiar kinked and braided structure.

In the final phase of the mission’s dramatic endgame, the spacecraft will pass through the gap between Saturn and the rings – an unexplored space only about 2,400 kilometres wide.

The spacecraft is expected to make 22 plunges through this gap, beginning with its first dive on April 27 next year.

A study led researchers from the University of Idaho in the US suggested that there could be two tiny, previously undiscovered moonlets orbiting near two of the planet’s rings.

The discovery was made from data gathered by the NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft which flew by Uranus 30 years ago.

New images obtained by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope confirmed the presence of a dark vortex in the atmosphere of Neptune.

Though similar features were seen during the Voyager 2 flyby of Neptune in 1989 and by the Hubble Space Telescope in 1994, this vortex is the first one observed on Neptune in the 21st century. The New Horizons spacecraft beamed back the final bits of data – a segment of a Pluto-Charon observation sequence taken by the Ralph/LEISA imager. It was the last of the 50-plus total gigabits of Pluto system data transmitted to the Earth by New Horizons since its historic flyby of the icy dwarf planet last year.