WASHINGTON: A novel catalyst breaks carbon dioxide into useful chemicals faster, cheaper, and more efficiently than the standard method, an advance that could make it possible to economically turn CO2 into fuels, scientists say.

The extra carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is changing the planet’s climate, and many chemists are working on efficient ways to turn it into other useful products, according to the researchers from the University of Connecticut in the US.

However, the researchers noted that carbon dioxide’s stability makes this tough. It’s hard to get the molecule to react with anything else.

The best existing technique to electrochemically break carbon dioxide into pieces that will chemically react uses a catalyst made of platinum, which is a rare, expensive metal, they said.

In the research published in the journal PNAS, the scientists created an electrochemical cell filled with a porous, foamy catalyst made of nickel and iron, metals which are cheap and abundant.

When carbon dioxide gas enters the electrochemical cell, and a voltage is applied, the catalyst helps the CO2 — a carbon atom with two oxygens — break off oxygen to form carbon monoxide, a carbon atom with one oxygen.

The carbon monoxide is very reactive and a useful precursor for making many kinds of chemicals, including plastics and fuels such as gasoline.

Not only does the new nickel-iron catalyst work well, it is also more efficient than the expensive platinum process it could replace, noted Yongtao Meng, a former graduate student at the University of Connecticut, and now a researcher at the Stanford University.

The electrochemical cell using the nickel-iron catalyst gets almost 100 per cent efficiency, according to the researchers.

“It’s almost unheard of. Typically in a good system you’ll get 90 to 95 per cent efficiency, but it might not be stable, might not work at the same low voltage or might not be cheap,” said Steve Suib from the University of Connecticut.

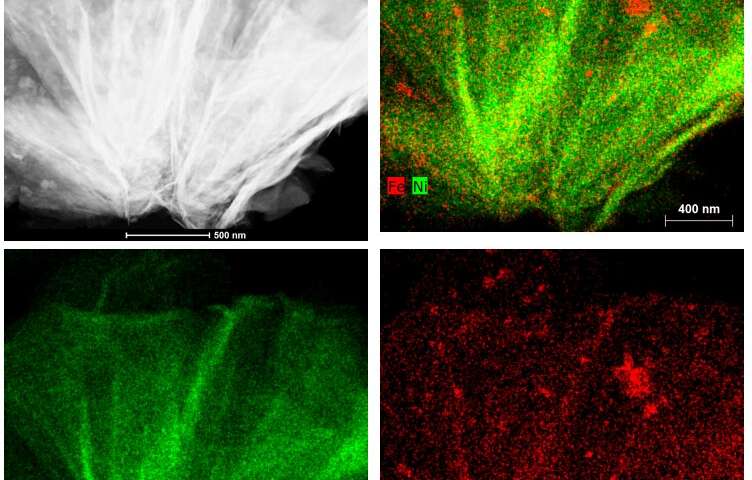

Suib’s lab used scanning transmission electron microscopy to map cross-sections of the new nickel-iron catalyst, revealing its internal structure.

Technically it’s a nickel iron hydroxide carbonate, with a porous structure that allows the carbon dioxide gas to flow through it, the researchers said.

Suib’s microscopy work showed the catalyst stayed intact and did not degrade from use.

The researchers noted that the next step in the process is to see if it can be scaled up, made in bulk, and tested in industrial situations such as power plants that produce large amounts of carbon dioxide as a waste product. (AGENCIES)

Trending Now

E-Paper