Suman K Sharma

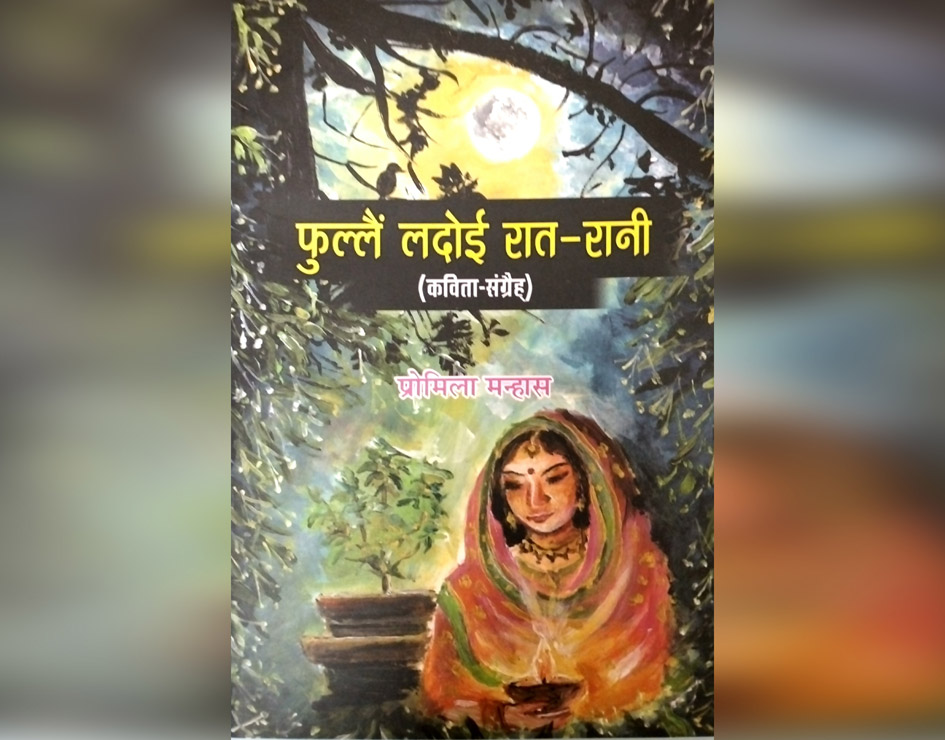

Promila Manhas has made her debut as a published author with a collection of Dogri poems, Phullain Ladoi Raat Rani (Classic Printers, Jammu, 2022).

Not too long ago, there was a fad among the literati to focus attention on the text itself. Only the text and the reader mattered, all the rest – and that included the author – were of incidental importance, if at all. But then the text does not exist of its own. If the author were not there, how would have the text come to the reader? It is the author who, acting as a highly developed channel, perceives the world, adds the magic of factor ‘x’ to it, and passes on the impressions to the reader by way of text. In so doing, s/he leaves an indelible mark of self on the text. A fair idea about the author, therefore, makes it easier for the reader to comprehend the why and wherefore of a literary work.

Ms. Promila Manhas (born 1970) belongs to the second generation of free India. Married, she holds a master’s degree in Botany and is currently teaching as a senior lecturer at a government school. She has been a voracious reader since her school days. Poetry came to her from the rural environment that nurtured her. She wrote her first poem – in Hindi – when she was in Class VII (23-25).

The 82 poems in the collection evince three major characteristics of Promila’s mental make-up: her deep-rooted feminism, the will to find her place in the sun and an unabashed realism. Significantly, a woman of many accomplishments, she is proud to remain the daughter of her family. The first poem in the book, titled “Maan” – Mother (29) is an encomium to motherhood informing the universe, as well as to her biological mother. The last poem, “Pita: Nain Hoi Sakde Kavita” – Father: No Poem Can Speak for You (174-176), is the poet’s personal accolade to her father.

The daughter now speaks in the voice of a sensitive, strong and assertive woman. The female foetus in its mother’s womb is not a pathetic creature languishing in a dark dungeon, but a future human being who urges the mother: “Don’t you lie dormant/Keep your eyes open/…. Your womb/Feels like a crib to me/Let me enjoy the ride/Allow me the time/To have my share of your affection (“Maassey da Lothadu” – A Piece of Meat (60)). A 20th century mother has this to say of her daughter: “My daughter/A sapling of my own century/Though me older than the country’s freedom/And she born in a country free/She refused to accept from her granny’s hand/The strands of her dad’s proud turban (“Photu Frame” – Photo Frame (31)). Yet, a grown-up woman rues that the walls of her house are “Overtopped by a concrete roofing/Neither they can walk/Nor can they fly/Standing still is their grain (“Ghar” – House (75)).”

Obviously, it would require extraordinary effort for a woman to come out of such constraining walls and realise her potential of “grabbing the skies at will”. Promila graphically describes the unlimited endurance called for in that ‘evolution’: “For being a superwoman/That evolution she passed through/She bore pain beyond measure/Shed tears without limit/Her hurts/She fomented herself/She picked up thorns with her eyeballs/She faced storms/Blocking her veins and arteries/All those blood clots/She melted for free-flow/With the heat of her zeal” (“Superwoman” (152-153)).

Promila, it seems, is a poet eager to go beyond terrestrial constraints. Her canvas spans the earth and the stars. In “Tare Gede Go-achi Kushwa” – Stars Are Lost Perhaps (164-167), she recollects how as a child she roamed the skies lying in her bed with Bebe, her grandmother. Bebe could not traverse the galactical distances, so Baby Promila packed her in a little box and lugged her along the Milky Way. Now a mature woman, the poet laments the disappearance of stars in the night sky –

“Perhaps, layer after thick layer of grime/Has settled perpetually/Between the earth and the stars/Ruffled, perhaps, the constellation/Is distancing itself from earth/To go to a safer place in the universe/To brighten it up/Perhaps…”

Now this is what may be called ‘factor X’ of the poet’s magic. A hard look at the reality is so engagingly intertwined with fantasy that we keep guessing which is which. Promila takes pleasure in making cliches stand on their head. Moon and moonlight have been traditionally associated with beauty and feminine charm. Who can forget Balkavi Bairagi’s beautiful song, “Tu Chanda main Chaandani….” sung by Lata Mangeshkar! But in “Chann Adhkad” – Middle-aged Moon (118-119), Promila lampoons the Moon as a wrinkled, tired and irritable oldish man; and his Moonlight, a worn out, hunchbacked (!) old dear. Clad head to foot in a dirtied white sheet and holding a walking stick in her hand, poor Chaandani bears her Chaand company till she can…

Anthropomorphism, the age-old poetic device to accord human traits to non-human phenomena, lends Promila’s poetry a dimension that she could not have achieved otherwise. Not only the moon and moonshine as man and wife, she turns the night-blooming jasmine (Cestrum nocturnum flowering bush) into a scented damsel bedecked in flowers lying in wait for her lover (“Phullain Ladoi Raat-rani” – Flower bedecked Jasmine (156-158). And the poet’s glasses? The pair becomes a wife long discarded by her husband who now values her with his life (“Kadar” – Recognition (159-160)).

Recently, a renowned literary figure of Jammu asked me what as a reader I look for in newly published Dogri authors. I said I wanted to see something out of the ordinary in them. Promila Manhas’s very first publication more than that meets my expectations.