Even th ough Sumantra had faithfully conveyed to him Raja Dashrath’s plea to return to Ayodhya after a short trip to jungle, Ram insisted on staying back. He persuaded Sumantra instead to carryhis messages to everyone dear to him in the capital.For the next fourteen years, he wanted to relinquish the life of a prince and live the life of a hermit.

ough Sumantra had faithfully conveyed to him Raja Dashrath’s plea to return to Ayodhya after a short trip to jungle, Ram insisted on staying back. He persuaded Sumantra instead to carryhis messages to everyone dear to him in the capital.For the next fourteen years, he wanted to relinquish the life of a prince and live the life of a hermit.

Balmiki says that Ram told Guha – the chief of boatsmen – of his desire to recede to uninhabited part of the forest on the far bank of the Ganga. He wanted to find a suitable place there to spend the period of his banishment (see Balmiki Ramayan, Ayodhya Kand, Canto 52). Sant Tulsidas introduces here a character by the name of Kevat to make the event livelier. This Kevat is a simple-minded unlettered boatman. He turns down Ram’s request for a boat with a logic of his own –

Chhooat sila bhaee nari suhai/Pahan ten na kath kathinaee//

Tarniau muni gharini hoee jaee/Bat paraee mori nav udaee//

(You are the one) whose mere touch turned a stone slab into a beautiful woman. (My boat is wooden). Wood can never be harder than stone. (If you sit in it), my boat too will turn into Muni’s (that is Rishi Gautam’s) wife. My boat will fly away, I will be robbed!

Ramcharitmanas, Ayodhya Kand, 99(iii)

Actually, behind the façade of his simplicity, Kevat was trying to be smart. Being an ardent devotee, he wanted to have the privilege of washing Ram’s feet and this he achieved by using his twisted reasoning. Highly amused, Ram played up to him, telling him to wash the dust off his feet diligently lest his boat should change into a woman. His heart’s desire fulfilled; Kevat rowed the boat to the far bank of the Ganga. Disembarking, Sita removed her diamond ring and Ram asked him to accept the fare. To that Kevat replied that washing his sacred feet he had earned the wages of his life-time. He wanted nothing more now. Yes, when they returned, he would be too happy to accept whatever they gave him.

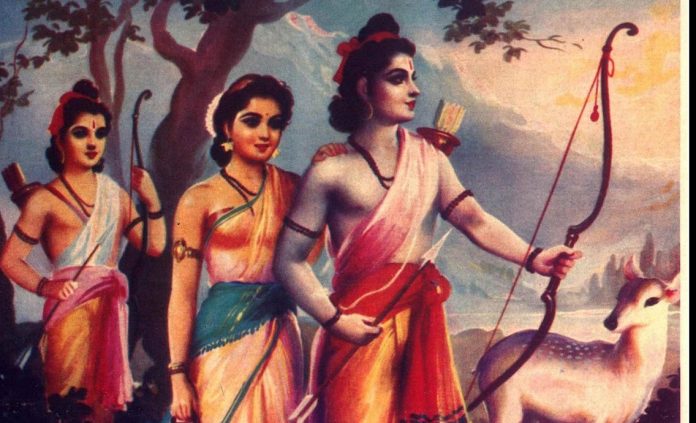

The three royals spent the night in the open – on beds of fallen leaves under a big tree. Ram understood that his consort Sita had willingly forsaken the comforts of a palace to live with him. But what about Lakshman? If it was not for the fraternal love, the prince had no obligation to go on living the life of want and suffering for fourteen long years. Ram also knew too well that his younger brother won’t leave Sita and him in the jungle and go home alone.

That made him think of a ruse which might compel Lakshman to rush back to Ayodhya. Ram called Lakshman aside for a private chat. He said that their father was quite old and grief-stricken because of separation from them. Kaikeyiby her manoeuvring had taken away from him what little vitality he had. With Bharat installed as the raja and Kaikeyi asserting her power behind the throne, there was no one who could save Raja Dashrath from coming to harm. He would have stayed on, Ram added, and prevented such possibilities to arise, but his vow to Kaikeyi forbade him. It behoved Lakshman, Ram pleaded, to go back to Ayodhya to ensure their father’s safety. He would have liked Sita also to go with him, but she too had her marital vows to abide with him.

Lakshman heard through Ram’s longish reasoning. In the end he replied to him succinctly: neither he, nor Sita was going away from him whatever be the circumstances in the forest or in Ayodhya. They just could not live without him. That sealed the argument. Ram, Sita and Lakshman were going to stay together for fourteen years.

At sunrise, they began to walk towards Prayag-raj, the Ganga-Jamuna confluence. Theirs was a pleasant and leisurely walk. A wide variety of trees and flowery bushes regaled them with their beauty and fragrance. The roar of the waters of two rivers was deafening. At a distance, Rishi Bhardwaj’s ashram made its presence felt with smoke rising from the fire places. Pieces of felled trees lay on the jungle floor.

Approaching the entrance, Ram and Lakshman asked an inmate to apprise the rishi of their arrival and seek his permission for their entry to the ashram. Rishi Bhardwaj was glad to have them with him. Learning of his vows of an ascetic life, he presented to Ram a cow and a quantity ofjungle fruits. He also invited the trio to stay with him as the place was peaceful and ideal for meditation. Ram told him courteously that he would prefer to settle instead in an isolated place since the ashram was too accessible and people would keep frequenting it to meet them. Bhardwaj then advised Ram to go to Chitrakoot, a mountain some 10 kos (about 30 kilometers) away from the ashram. It was the abode of quite many venerable rishis who had since departed this world. In the thick forest creatures like bears, monkeys and lemurs roamed freely. It would serve them as a good place for isolation.

They stayed at Rishi Bhardwaj’s ashram for the night. The following morning, the rishi walked with them for some distance and then gave them precise directions to reach their destination. “Raghunandan!” the Rishi said,”You will walk westwards to the spot where the Jamunaflows opposite to its currentbecause of the onrush of the Ganga waters. Then, carefully following the footprints of the wayfarers, approach the bank of the great river, make there a raft for yourselves, and in that raft row across to the other bank of the Jamuna….”

When Rishi Bhardwaj made a move toreturn to his ashram, Ram bowed to his feet, expressing his gratitude. The three of them then began their journey forChitrakoot. Lakshman would make there a ‘Parnkuti’ – a leaf hut – to provide them shelter against the elements. Surrounded by the lush green forest and in company of amiable birds and beasts, they looked for a serene life ahead, secluded from the rest of the world. Little did they know that a large crowd would be descending on them in a matter of days.