WASHINGTON : Scientists have successfully tweaked the process of photosynthesis to make it more efficient and increase plant productivity by raising the level of three proteins involved in the process.

Many years of computational analysis and laboratory and field experiments led to the selection of the proteins targeted in the study. Researchers used tobacco plants as it can be easily modified.

“We do not know for certain this approach will work in other crops, but because we are targeting a universal process that is the same in all crops, we are pretty sure it will,” said Stephen Long, professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in the US.

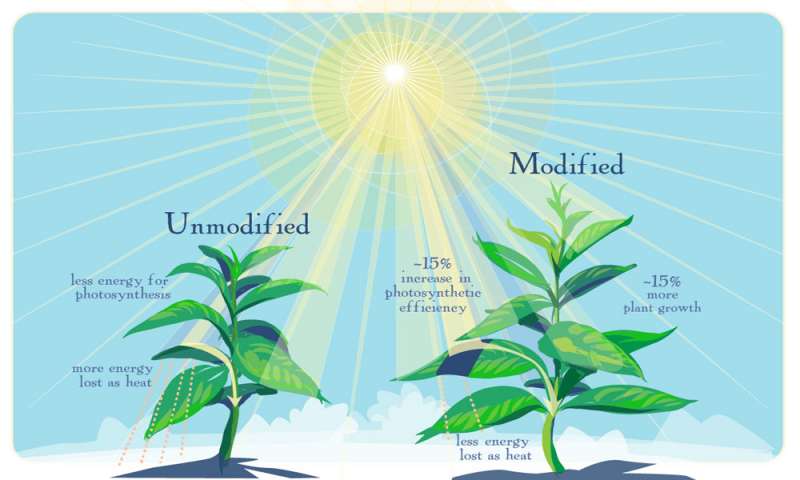

The researchers targeted a process plants use to shield themselves from excessive solar energy.

“Crop leaves exposed to full sunlight absorb more light than they can use. If they can not get rid of this extra energy, it will actually bleach the leaf,” said Long.

Plants protect themselves by making changes within the leaf that dissipate the excess energy as heat, he said. This process is called nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ).

“However, when a cloud crosses the sun, or a leaf goes into the shade of another, it can take up to half an hour for that NPQ process to relax. In the shade, the lack of light limits photosynthesis, and NPQ is also wasting light as heat,” Long said.

Researchers used a supercomputer to predict how much the slow recovery from NPQ reduces crop productivity over the course of a day.

These calculations showed “surprisingly high losses” of 7.5 per cent to 30 per cent, depending on the plant type and prevailing temperature, Long said.

Researchers suggested that boosting levels of three proteins might speed up the recovery process.

To test this concept, they inserted a “cassette” of the three genes – taken from the model plant Arabidopsis – into tobacco.

“The objective was simply to boost the level of three proteins already present in tobacco,” Long said.

The researchers grew seedlings from multiple experiments, then tested how quickly the engineered plants responded to changes in available light.

A fluorescence imaging technique allowed the team to determine which of the transformed plants recovered more quickly upon transfer to shade.

The researchers selected the three best performers and tested them in several field plots alongside plots of the unchanged tobacco.

Two of the modified plant lines consistently showed 20 per cent higher productivity and the third was 14 per cent higher than the unaltered tobacco plants.

The study appears in the journal Science. (AGENCIES)