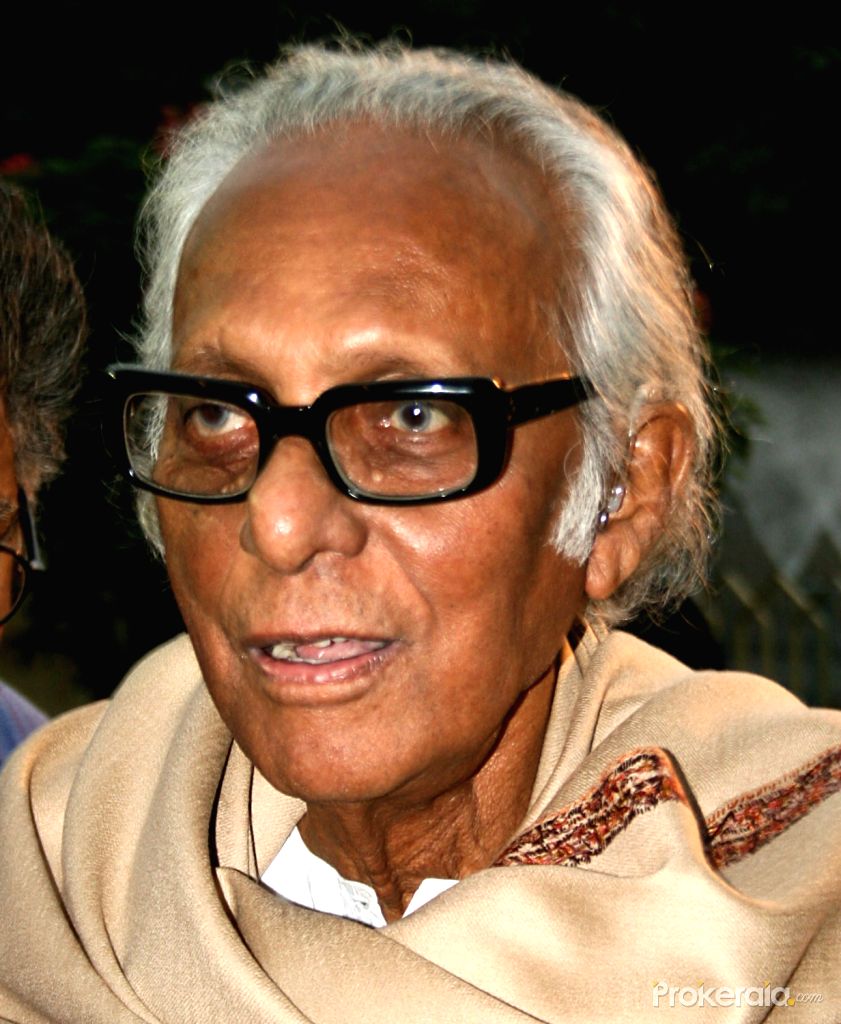

With the passing away of Mrinal Sen on Dec 30, an era in Indian arthouse cinema came to an end. Sujoy Dhar remembers the many candid interactions with the auteur and a legend of our time

As a young man, Mrinal Sen had no fierce passion for cinema and he was not even a habitual cine-goer. “My foray into films was purely accidental,” he once told this writer in between cups of black tea at his south Kolkata residence in Beltala area.

One day in the 1950s, Sen came across Rudolf Arnheim’s book “Film” in the catalogue room of the then Imperial Library. It was a book on the aesthetics of cinema, on its philosophy and socio-political relevance. Well, as they say, rest is history.

Loved and hated equally for projecting his views with unabashed candour, Mrinal Sen with his strong Marxist leanings, rewrote the language of films and in the course of that journey won awards in Cannes, Berlin and everywhere else. Besides Bengali and Hindi, he also made films in Oriya and Telugu.

At the end though, Sen was a spent force and his last few films were better not made I strongly felt. His Dimple Kapadia starrer “Antareen” was also not a film I liked though he told me in an interview: “I was overcome with terrible sense of emptiness for a long time benumbing my creativity. The alienation I experienced led to a film like Antareen [where two alienated stangers- Dimple Kapadia and Anjan Dutta- one night starts talking over the phone as their lives start revolving around the telephonic conversation without ever meeting]”.

Born on May 14, 1923, in Faridpur, (now in Bangladesh), Sen came to Kolkata later and studied physics. Soon he was involved with the cultural wing of the Communist party and got associated with the Indian Peoples Theatre Association.

Mrinal Sen made his first feature film in 1953 (a disastrous debut as he himself told me), but it was his second film Neel Akasher Nichey (Under the Blue Sky), which brought him to limelight.

Set in the background of the ultimate rising against the British rule in Kolkata, the film told the story of an immigrant Chinese wage worker, Wang Lu, and the bond he developed with a housewife (Kali Banerjee and Manju Dey essaying the roles respectively) who was also involved in the freedom struggle of India.

However, Neel Akasher Nichey is still not a signature film of Sen who scripted a new language of cinema in the following years and decades to register his protest against an unforgiving capitalist society.

His third film, Baishey Shravan (Wedding Day, 1960) first earned him the recognition as a filmmaker of international repute and skills.

What brought Sen more fame and controversy was his Calcutta Trilogy depicting the Naxalite Movement of the late 60s and early 70s with the films- Interview, Calcutta 71 and Padatik (The Guerrilla Fighter).

In the last film of the series- Padatik- he actually reassessed the movement that rocked Bengal and created ripples across India.

A voyeur with camera Sen imprisoned on celluloid real life events taking place in Kolkata in the 70s- the political rallies and the police baton-charge and the protests every day on the streets. His films were a telling commentary of the times Bengal experienced.

However, with time he learnt to become more cautious about his political leanings. “I was at that. point of time trying to point my finger at the enemy outside,” he said of the films.

He in the second half of 70s started making film which were marked departure from the political films. He concentrated more on soul searching and targetted the enemy within ourselves. This was somewhat reflected in Hindi film Mrigaya (1976 in which Mithun Chakraborty made his debut). But his introspective films started with “Ek Din Pratidin (And Quiet Rolls the Dawn) in 1978.

This was a film of an unmarried working girl, a sole bread earner of a family who does not return one night, setting off a chain of introspective reactions from her rather selfish family members.

And then came a film like Kharij (The Case is Closed), a slap on the face of middle class, where a servant left to sleep beneath the staircase, died of asphyxiation in the kitchen where he had taken refuge to escape the freezing winter night.

The process of introspection continued with films like Shabana Azmi starrer Khandhar (The Ruins, 1982) and earlier Smita Patil-Srila Majumdar starrer Akaler Sandhane (In Search of Famine, 1980).

Sen, a Padma Bhushan and Dada Saheb Phalke awardee, paved the way for parallel cinema in India along with Satyajit Ray and Ritwick Ghatak, but he would also be self-criitcal.

“Deep in my heart I know my areas of mediocrity. And the professor in the film Ek Din Achanak who walks out of his family on a stormy day never to return, I too feel that the saddest thing in life is that we live only one life. Today I feel like starting all over again,” he would tell me in one interview, leaving me surprised. (TWF)