Suman K Sharma

It was about quarter-past 5 on that cold evening of Friday, January 30, 1948. The place was the compound of the Birla House in New Delhi. Enfeebled by a 6-day fast he had kept to persuade Hindus and Muslims to desist from further bloodshed, Mahatma Gandhi was late for his evening prayer meeting. Nathuram Godse appeared from nowhere, touched his feet reverentially and then fired four shots at him point blank. As Gandhiji fell to the ground, the life-story of an extraordinary personage came to an end. In his death, the Mahatma set an example of how one should live and die for his or her convictions.

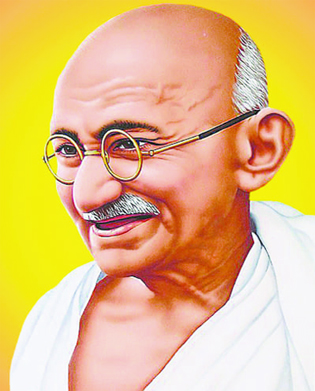

No wonder that three quarters of a century on, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi still seems as familiar to us as his face on a crisp currency note. The youngest of six siblings, he was born at Porbandar, Gujrat, on October 2, 1869 to Putlibai and Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi. They called him ‘Monu’ out of affection. If you had walked down the streets of Porbandar during the mid-1880s, you would have found Monu or Moniya a boy of average intelligence, susceptible to good as well as bad influences. In May 1883, barely 13, he was married to Kasturba Makhanji Kapadia, who was six months older than him. He became attached to her dearly. Much later in his life, Gandhi-ji would sorely repent the teenage passion for his young wife that could wrench him away from the bed of his dying father.

At 18 he was a matriculate and his family decided to send him to England to study law. It was not an easy decision to take for an orthodox family that belonged to a much more orthodox community of Modh Baniyas. The Gandhis were excommunicated for being mlecchas. Mohandas, on his part, assured his kin that he would remain faithful to his wife and not touch alcohol or meat during his stay abroad. His three year stay in London was uneventful except that he made use of his spare time in passing the London Matriculation examination as well. He failed for the first time because of Latin. In the second attempt, he dropped Latin for another subject and was declared successful. Acquiring a degree of law was relatively easy. On June 11, 1891, the gawky Indian youth with prominently standing out ears became a registered ‘barrister-at-law’. Intellectually, he had fortified himself in London with a thorough knowledge of English language, basics of English law and perceptions of the Latin lawgiver, Justinian. Spiritually, he had picked up elements of Gita (he read it in English translation) and The New Testament. He got well acquainted with the western life-style and dressed up like any contemporary Londoner. More importantly, Gandhiji, had become a true admirer of Pax Britannica.

The following two years that he spent in India did not bring him any case. Yes, he appeared before a court in Bombay (now Mumbai), but as his client watched helplessly, he stood tongue-tied before the judge. That was Gandhiji’s first and the last case as a barrister in India.

Destiny was calling him across the seas to South Africa, where he would spend two decades – from 1893 to 1914. It was here that the rough and tumble of happenstance hewed his intrinsic qualities of adherence to truth, compassion, non-violence and unfailing commitment to fight for what he thought was wrong, and stand for what was right. When a ship brought him to the Durban port, Gandhiji was a rookie, unprepossessing man of law in the employ of an affluent merchant. But as he bade adieu to South Africa, he had turned into an icon who could look into the eyes of the mightiest of the mighty and have his voice heard all round the world. It was in South Africa that he experienced – and relentlessly fought – the brutality and unreasoning of apartheid at its rawest. His unbounded compassion found an expression there in tending the afflicted with bubonic plague in Johannesburg. In Phoenix Settlement and then in Tolstoy Farm he inculcated in his followers the principles of truth, celibacy, selfless service to the community and the importance of maintaining cleanliness. Working pro bono to defend indentured labourers caught in the web of harsh laws, taking up the cause of the Indian immigrants in his campaign against the Immigration Amendment Bill and the Franchise Amendment Bill, Gandhiji honed his legal acumen and learnt how to conduct mass movements successfully. It is anybody’s guess that the great precepts of Satyagraha, Brahmcharya and vegetarianism became a way of life with him because of the immense tasks he had taken in hand in South Africa.

After a short stay in London in 1914, Gandhiji returned to India in January 1915 and was accorded a hero’s welcome. Travelling throughout India, he familiarised himself with the ground conditions, and in the year that followed year he set up the Sabarmati Ashram at Ahmedabad in Gujrat. From that point till his assassination, Gandhiji was at the helm of nation-wide movements to set right what bothered his countrymen. In 1917, it was the Champaran Satyagraha to alleviate the miseries of Indigo cultivators. In 1919 he lent whole-hearted support to the Ali Brothers in Khilafat Movement to reinstate the Caliph in Turkey. In 1920, in the fallout of the Jallianwala Massacre – and the kid-glove treatment the British government gave its perpetrator, Brig Dyer – he launched the Civil Disobedience Movement to peacefully demonstrate to the Gora Sahibs that they could no longer take Indians for granted. The Civil Disobedience Movement of 1930 was also in that vein. He led the Dandi March in the same year to break the Salt Act to tell the Britishers in no uncertain terms that their oppressive laws would not to be respected. Then, in 1942, Gandhiji launched the Quit India Movement of 1942 as an ultimatum to the Raj that it had to wind up in India.

Gandhiji protested not only against the British Raj (for which he had a soft corner till very late), but he was equally given to show his displeasure or disagreement with his own people. His most potent weapon on such occasions was fasting. He started the practice in 1913 as an experiment in self-purification in the Phoenix Farm, and the last time he was on a fast was in January 1948, a couple of weeks before his assassination. In between, he had fasted on 17 more occasions. It is no wonder that the authorities of his times found him a thorn in their flesh. Four times he was sent to jail in India – in 1920, 1930, 1933 and 1942.

His admirers like the Nobel-laureate Rabindranath Tagore gave him the moniker of ‘Mahatma’ for his austere ways and service to humanity. Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose called him ‘Bapu’. The pugnacious British Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill slighted him as ‘a half-naked seditious fakir’. Indeed, Gandhiji was a man who could never be ignored. He evoked intense emotions of adoration or antipathy in equal measure. He still does.

Perhaps it was because of the apparent contradictions in his ideas and actions. In South Africa’s Boer War, he sympathised with the Boers; yet it was for the British army that he volunteered. He was a strong votary for India’s freedom, yet as late as the 1930s, he not only considered himself as a faithful subject of the Raj but would have been content with ‘Dominion’ status of the country. As an individual he was a peaceful and empathetic person. But when it came to seeing his ideas in action, he showed his despotic strain to mentally coerce those around him to obey him irrespective of their personal likes or dislikes. His lifelong vow of Brahamcharya -celibacy even in married life – is one such instance. It was fine for him to be brahamchari at the age of 42 during his days in community living in South Africa. Why impose it on the other adult members of the community? ‘But why not? If I can do it, others too can and they should,’ he would have reasoned. That was the trait which made Gandhiji, a 5’5 man of barely 46 kilos, weightier than the stoutest of men of his times.

Two days after his demise, an editorial in the Hindu expounded Gandhiji’s charisma in these words –

“He was essentially a man of action, not of sweet words. He had further, what many others lacked, a constructive faculty. He would not merely denounce other men and other measures; he would show them a way and a method better than theirs. Gandhiji had a philosophy of his own and a way of life steeped in Sanatana Dharma; and neither that philosophy nor the way of life to which it led one was such as may be dismissed offhand as obscurantist.”

feedbackexcelsior@gmail.com

Trending Now

E-Paper