Dr. Anupama Vohra

Name of the Book: From Home to House Writings

of Kashmiri Pandits in Exile

Publisher : Harper Collins

Publishers, India .

Year : 2015

Pages : 216

Price : 350/-

The book From Home to House:Writings of Kashmiri Pandits in Exile, published by Harper Collins Publishers India in 2015, has been edited by Arvind Gigoo, Adarsh Ajit and Shaleen Kumar Singh. All the three editors are authors, translators and reviewers. Gigoo and Ajit are Kashmiri Pandits, whereas Shaleen Kumar Singh is a researcher from Badaun in UP and teaches English at a Post-Graduate College in UP. He also edits an e-journal Creative Saplings.

From Home to House: Writings of Kashmiri Pandits in Exile is an anthology of short stories, excerpts from novels and other books, and write-ups on different problems, perspectives and themes connected with the migration and displacement of the Kashmir Pandits from their homeland, that is, Kashmir. All the stories and write-ups (except one article) have been penned down by Kashmiri Pandit writers away from their homeland- Kashmir. Seven write-ups and two translations have been contributed by women. Two women are translators. The preface to the book From Home to House: Writings of Kashmiri Pandits in Exile gives a bird’s eye view of the story of Pandit migration.

The book has two sections, Fiction Section and Non-Fiction Section. There are seven short stories and five excerpts from the novels written by Pandits in the Fiction Section. Two Kashmiri short stories and one Hindi short story have been rendered into English. Four short stories are originally written in English. These underscore the nuances of relationship of Kashmiri Muslims with Kashmiri Pandits. K L Chowdhury’s short story “The Survivor” is about that horrible night of gruesome massacre of Pandits in Kashmir which not only shattered their lives but also cut them off from their roots. In Rattan Lal Shant’s “Air You Breathe” a Pandit goes to Kashmir to attend a meeting for the revival of old community relationship but returns a disillusioned man. Santoshi’s “Kidnapping” is about the friendship of a kidnapper and a Pandit. Rahbar’s “Addition, Subtraction and Division” reflects the dilemma of elderly Pandits who “like beans scattered all over” see the end of Kashmiri Pandit culture in inter-caste and inter-community marriages. The excerpts from the novels written by Tej N Dhar, Siddhartha Gigoo, Adarsh Ajit and Juhi Kuchroo and Manik Kuchroo depict pain, suffering and predicament of Pandits— their fears, alienation in a tent, friendship and enmity between Muslims and Pandits, and the horrible condition of a Pandit family in a temple. Excerpt from Khema Kaul’s “Samay Ke Baad” narrates the exile experiences of three Pandit women in Ajmer, far away from Kashmir. Love-hate relationship, anger, aloneness, misery and love of homeland are the binding threads running through the stories and the excerpts.

Non-Fiction section contains twelve essays, some snippets and two excerpts from two books: one a nostalgic memoir The Tiger Ladies by Sudha Koul recalls her youth spent in Srinagar amidst the simmering anti-nationalism while the other The Story of a Frozen River is a record narrative of the day-to-day experiences that a kidnapped doctor S N Dhar undergoes. The author of the snippets, that is, cameos, is satirical: “First Aid-We fear for your lives. We won’t harm you but we can’t stop others. Leave everything here. You will be safe.” K N Pandita’s A Moment of Introspection presents a new approach towards life and propagates a revolutionary spirit to be cultivated both by Pandit men and women. A couple of articles point out the fact that Kashmiri Pandit migrants are tourists to their land of birth. M K Kaul Naqaib’s “Life in the Camp” is a testimony of the inmates-.old, middle-aged, young- of migrant camps. R N Kaul’s “19 January 1990” is a chilling narrative of the horrible night which snatched the “lap of motherland” forever from the Pandits. A filmmaker Ajay Raina writes about his films and Kashmir: “I became a recording instrument…my own subject and object…” Shyam Kaul in “Humour in Exile” highlights through incidents and anecdotes the displaced Pandits sense of humour which helps them to survive in miserable heartbroken conditions. In “Pandits and Dogras” Shaleen focuses on a new way of life created through the exchange of ideas and cultures between the two distinct communities The point-of-view of a young Pandit Deepak Tiku working in an MNC presents the thinking of the new generation of Pandits: “…nothing to fall back upon except faint memories…we were thrown into the factories to make ATMs out of us…” The description of Aparna Sopori’s “My Father’s House” in Kashmir is pictorial, vivid and full of pathos. M L Kak’s article “Pandits And Narendra Modi” reflects Pandits ray of hope-“good times” to come again- with the emergence of Narendra Modi as the head of the Indian state. These writings reflect the Kashmiri Pandits’ nostalgia, their past, their dreams, their fears and their attempts to come to terms with their present and carve a place for themselves in future. These works are the reflections of a lost, scattered and an uprooted people in an alien land. The writings touch most of the characteristics and facets of the Kashmiri Pandit exiles, that is, their feel of history, their interest in the day-to-day happenings of the world, their passion for political events, their sense of pride and sorrow out of their homeland. The short stories and excerpts show how the Pandits are living in uncomfortable situations. These writings mediate and illustrate their dissent and hope.

Brief introduction to the authors and translators of the articles, stories and excerpts at the end are useful and informative. Some young Kashmiri Pandits have contributed their write-ups to the book. This is a heartening trend, and I am hopeful that the new crop of young Kashmiri Pandits will write their impressions of Pandit migration and its effect on them so that the young emerging voices don’t go unrecorded, unheard and unnoticed.

It is a significantly important book for the Indian intelligentsia, statesmen, researchers, teachers and writers for it will introduce them to the darkest chapter in the history of modern Kashmir and the responses of the victims to it. The book is a noteworthy and valuable addition to the new genre- “Literature in Exile” that has taken shape in India for the first time after the independence of the country. HarperCollins Publishers India, Noida, deserve accolades for having published a very important and significant book for the readers.

Hundreds of writers among the Kashmiri Pandits have contributed to creative and non-creative writing. Though I know it is not possible to include all in a single book still I wonder whether the representative authors find their writings here. The writings of Pandit authors require volumes. Even many non-Kashmiri Pandit researchers and writers have written much on Kashmiri Pandits in exile.

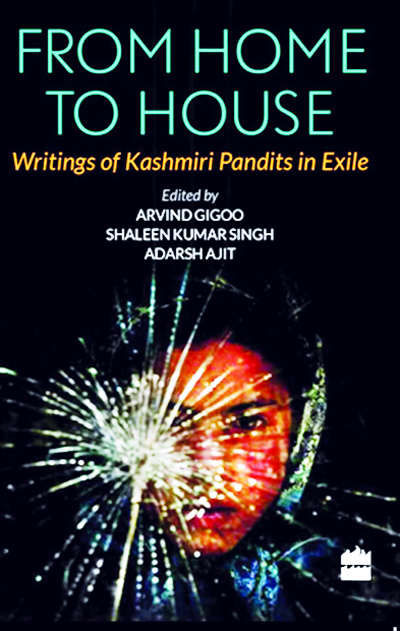

The photograph of a girl looking outside through a cracked windowpane decorates the cover of the book From Home to House. The photo catches the essence of the book. The book is a must read for everyone to have glimpses into the lives of an educated community uprooted from their “Paradise on Earth” to face sorrow, victimization and neglect in their own country.

(The reviewer is Associate Professor of English , DDE, University of Jammu and works in the area of Regional Literatures. She can be reached at vohranu@gmail.com)