By Dhurjati Mukherjee

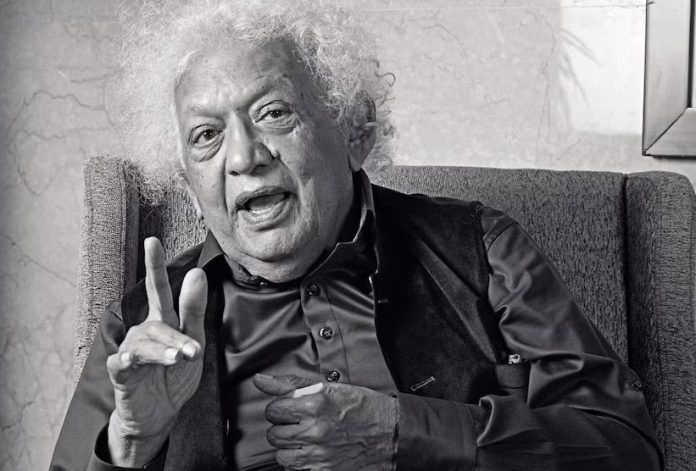

Prof. Meghnad Desai, the well-known economist has made an insightful observation that economics as a subject lost its concern for the poor somewhere along the way in his recent book titled‘The Poverty of Political Economy: How Economists Abandoned The Poor’. It has been pointed out that the Smithian concern for the greater good was lost long back during David Ricardo’s works where the value of a good was determined by production and not by exchange. It was during this time that economics started losing its concern for the poor.

Desai referred to a Cambridge economist, Prof. Arthur C. Pigou, who, according to him, was the first to be worried about inequality and wastage that capitalism brought about. Desai has aptly called to promote a more humane economy. His reference for a basic income for all and ideas on how to make it feasible are greatly relevant today. Though some economists oppose universal basic income primarily due to fiscal constraints and also people losing the incentive to work, theseare not quite judicious arguments.

In India, it has been pointed out by several economists that the pro-rich and pro-urban policies followed by the ruling dispensation are meant to better the conditions of the upper echelons of society. Projects and programmes are taken that greatly make life easy for the rich and the upper middle class. Whether it is education and health, this section prosper because they can pay and get the best facilities while the vulnerable and marginalised communities suffer for an existence. The existence and conditions of living of the latter class in our country cannot be dreamt by economists and social scientists in the West.

One may refer here to Congress leader, Rahul Gandhi’s famous slogan ‘jitni abadi, utna haq’which envisaged equitable distribution of community as sets among different castes based on the respective share of the population by a caste-wise enumeration. But political leaders only think of lower castes like tribals when elections are around. And due to recent elections in Jharkhand, the focus now is on tribals.

But the recent verdict of the Supreme Court that the concept of material resources of the community could not extend to coveras sets of private citizens has attracted much attention and debate. It is surprising that when inequality has been widening the apex court has given such a judgment, there by putting a bar on redistribution or government’s acquisition bids. Thus, acquisitions would be quite difficult but the concentration of resources in the hands of private commercial houses would not in anyway serve the interests of society.

The role of the private sector in India is quite deplorable as its welfare activities are quite limited compared to the Western world. Moreover, work place exploitation, extended working hours and other inhuman activities in the private sector has put an obstacle on employment generation. There have been allegations that a new breed of corporate giants are using state machinery to stifle competition.

In recent years, private business has entered that health sector in a big way as this is the best avenue of reaping profits without much hassles. While the government extends facilities to the health sector to set up hospitals on the condition that a number of beds would be reserved for the poor, this is not adhered to in practice and the states do not have any monitoring mechanism to check this.

The same is the case in the education sector where big institutions of business houses are set up with very high annual fees that only the rich and the upper middle class can afford. Though educational standards are commendable, this education is limited to a very small segment of society. There is no place for the poor in either getting access to education or health facilities in private centres.

It is in this situation that the apex court has protected the resources of the private sector and obviously its distribution amongst the community cannot be done. Gone are the days of Vinobaji’s bhoodan movement where he urged the rich to give land to the poor and those who cultivated their land. The concentration of resources in the hands of the private individuals will further get entrenched with this judgment, which obviously comes as a setback to social activists and the larger community.

In recent years, one may mention the observation of Sam Pitroda who had vouched for the need for an inheritance tax that this prevalent in the US and many other countries. In the US, more than half of the wealth of the rich gets transferred to the government after their death. Many economists and institutions like Oxfam had vouched for implementation of such a law in India. Can the government not bring an inheritance tax law whereby say around 20-23 percent is transferred to the government for welfare of the poor and the oppressed sections?

There is thus enough reason to find justification in Meghnad Desai’s observation of economists and planners having forgotten their concern for the poor. And this is very much manifest in India where resources are a huge constraint to development and such steps could augment government’s funds to transform the rural sector and the living conditions of the lower echelons of society.

The concentration of power and wealth in the hands of the business class and their subsequent funding of elections have made them an important class who dictate terms to most political leaders of the country. Their craving for more wealth and neglect of the vulnerable sections is a part of the political culture of the country. There is absolutely no one to listen to the poor, to the lower castes and the economically weaker sections. They do not have any rights in society and the government machinery is not interested in looking after their problems. It is indeed distressing to note that the lack of proper governance as also the fact that bureaucrats come mostly from the upper classes make the mimmune to grass-root problems and neglect of the marginalised.

Will the condition not improve in the coming years? Even the most optimist will agree that though the oretically the answer may be position, in reality this may not be possible. The materialist trend that is evident the world over as also the privatisation strategy being adopted, there is little possibility of the focus concentrating on the welfare and well-being of the poorer sections.—INFA

(Copyright, India News & Feature Alliance)

New Delhi

11 November 2024