Autar Mota

Chronicling human pain and suffering is a formidable task that demands enormous objectivity, conceptual clarity, compassion, sympathy and truthfulness. A writer of this genre does not need the deftness of balancing to conciliate or the skill to incite. He needs to speak what is true. When truth is spoken, it takes no sides and passes no judgments.To a reader it is more acceptable than packaged and dressed facts. A writer, who remains faithful to truth, acts like a mirror. And a mirror alone reflects truthfully whatsoever is brought before it. Somehow, I have a feeling that in a civilized society, no man is shy of looking at thesemirrors that neither doctor nor dress up facts. At least they create a scopefor knowing what we are, what we could have been and what we shouldbe.

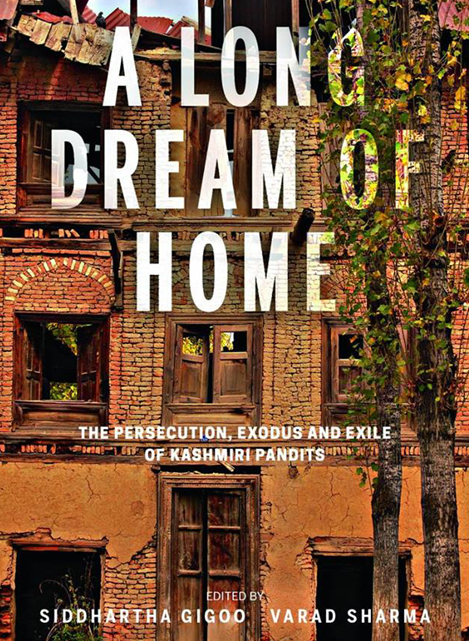

Four Kashmiri writers who have writtenin English on what happened in Kashmir during the past many years are Tej N Dhar, Basharat Peer, Rahul Pandita and Siddhartha Gigoo. But after reading the book ‘A Long Dream of Home’ I have found twenty-nine more writers of painful memoirs belonging to three generations of Kashmiri Pandits. They are the chroniclers of human pain and have proved themselves as masters in their art of writing.

Fear, mistrust, violence, death, destruction and failure of leadership led to tearing apart of the Kashmiri social fabric that had tolerance and tradition as its wealth. When Angry and misguided youth took over a movement against India at someone’s behest, promising poor natives the light of independence, they actually threw them into the fires of death and destruction. They gave nothing beyond killings, bloodshed, empty houses and a fearfully meaningful silence.

And unnoticed went the woes of the miniscule minority (Pandits) when they became soft targets. What option did they have when the newly acquired guns were brazenly directed towards them for no fault of theirs? They left in panic and fright, unsure of themselves.

The book under review has twenty-nine memoirs, each memoir a class apart from the other. To begin with Indu Bhushan Zutshi’s “She Was Killed Because She Was an Informant; No Harm Will Come To You” is a spine chilling narrative. Here we read that the killing of the nurse Sarla Bhat initially evokes resentment among Muslims in her home town Anantnag. But then comes a diktat from the local militant commanders for boycotting the family of the girl because according to them, she was a ‘police informant’. In fright, the sympathetic Muslim neighbours suddenly disappear from the scene. It became extremely difficult for the Pandits to cremate the girl who had also been sexually abused in captivity for four days. The family of the victim continued to look for sympathy and support from their neighbours and friends but fear, mistrust, suspicion and an atmosphere of hate stopped them from coming forward. It is a moving tale of helplessness, humiliation and betrayal.

Pran Kishore comes up in his inimitable style to present his eyewitness account of the filming of his tele-serial Gul Gulshan Gulfam in an atmosphere charged with terror and threats. His portrayal of the elderly houseboat owner Haji Samad Kotroo, with whom he had personal relations, is moving. Contribution of B L Zutshi and his colleagues in the establishment of camp schools and colleges for the Kashmiri Pandit students was a very great effort at that point of time. These details are given in Zutshi’s ‘Camp Schools and Colleges for the Displaced Students’. And Ramesh Hangloo established the Radio Sharda to preserve Kashmiri Pandit language, culture and tradition. Presently this RadioSharda is a household name with Pandits and is a part of each family. Arvind Gigoo in his ‘Days of Parting’ uses small sentences with simple English words to create an everlasting impression. His style is effortless and focused and comes closer to Sadat Hassan Manto. This memoir contains a story within a story, a diary within a diary and an episode following another episode when mistrust was the only language of communication.

The anecdotes intensely convey the apparent and the veiled. Arvind Gigoo’s narrative has two letters addressed to Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri Muslims. These letters are like Manto’s letters to Uncle Sam.

Adarsh Ajit in ‘Ya Allah, they have killed them; pour some water into their mouths’, shows how his relation with Muslims turned bitter. He writes about some gruesome killings that he saw. His depiction of the changing character and personality of his neighbours and friends is painfully realistic.

Dr.Kundan Lal Chowdhury in his diary/narrative ‘It is For Your Own Good to Leave’ describes his life of pain and uncertainty from 1989 up to 1990. Sushant Dhar in Summers of Exile paints the horrors of camp life. The first page of the article is loaded with meanings where the author is talking of his permanent address. And Santosh Kumar Sani in ‘From Home to Camp’ paints his horrible life as lived in camps and the cause of his running away from Kashmir. Rajesh Dhar in his ‘Knights of Shiva’painfully describes the molestation of some Pandit women. ‘Two neighbours and well-wishers of the Pandit accompanied him to his place. One said: My dear brother, you have no danger from us but I can’t say anything to my son…..Some strangers from another village were talking about you….Our youths are uncontrollable. I am silent when they talk….Now you have your time and we have our time.’ PL Waguzari and Kashi Nath Pandita in their narratives describe the mental condition of the Pandits in the nineties and how they fled the valley out of fear and terror created by the militants and jihadis. The description of Tika Lal Taploo’s death and the subsequent exodus is painful. Maharaj Krishen Naqaib’s description of the morning in Srinagar is like a tense scene from the TV serial Tamas. Badri Raina’s ‘Remembering the Unforgettable: Kashmir as She Made Me’is nostalgia of the highest order. He records how Kashmir shaped him into what he is. He writes about his visits to Kashmir with feeling and conviction.

Siddhartha Gigoo in his memoir ‘Season of Ashes’ describes the Alzheimer’s disease that his grandfather developed out of Kashmir and the death of his grandmother who died inSrinagar SMGS Hospital in 2012. He writes:

‘The ward staff saw us off at the Hospital gate. They hugged us. Some cried. She died in her home. We immersed her ashes in the Chenab. Where does this river go? I ask myself? I remembered that the river flows into Pakistan.’

‘My House of Stone’ by Neeru Koul is brilliant in conveying her nostalgia beautifully in excellent prose. Other narratives that I enjoyed reading are ‘Pomegranate Tree’ by NamrataWakhlu,’The Day I Became a Tourist in My Own Home’ by Minakshi Watts and ‘Inheritance of Memory’ by Varad Sharma. ‘Roses Shed Fragrance’ by Prof. Rattan Lal Shant comes so beautifully that it leaves you thinking. It has all the ingredients of a master story.

‘ Prithvi Nath Kabu in ‘Seasons of Longings’ talks about his life in exile when his son was killed in Gool. Nikhil Koul in ‘An Imaginary Identity’ says that memory of Kashmir lives in the consciousness of young Kashmiri Pandits. Tej N Dhar in ‘Dear brother, our part in this story is over’ says that he was forced to leave Kashmir because he was being watched by the militants.

This book presents a range in pain and suffering, a pain that has been experienced and felt and presented truthfully. Albert Camus once said:

‘Lying is not saying what isn’t true. It is also, in fact, especially saying more than is true and, in case of the human heart, saying more than one feels.’

I observe that all the narrators in this book have not said anything that is not true or that has not been felt or experienced by them. Most of the stories are overflowing with emotions conveyed from depths of human heart. This is a book for allthe readers—-Kashmiris and non-Kashmiris—- since it tells them what precisely happened and how it all began.

Trending Now

E-Paper